The number of infringements was endless and also involved objectively minor offenses such as do not say hello due to distraction, reluctantly following an order or Don't keep silence when it was prescribed. We can instead agree on heavy sanctions for offenses considered very serious such as do not observe due precautions when handling powders and open flames, absences that did not cover the ends of the desertion, sleep or be distracted during guard duty (which for an officer were always punished with rigorous arrests) or leave the place without permission.

Some infractions were typical of the sailing era such as walking on the windward quarterdeck, finding oneself or sitting in certain points of the ship reserved for superior officers or guard personnel and non-commissioned officers who showed up without their cap and without the rush in their hands, the emblem, were punished. of their authority, which they willingly made use of by lashing less than zealous subordinates.

There was a lot of attention regarding the order of the uniform and one's person which also concerned the civilian personnel on board who did not wear uniform but who always had to be decently dressed (1). The extent of the punishment was up to the judgment of those who inflicted the punishments, but the legislation was vague and, except for a few cases, the choice between these was essentially arbitrary.

Generally, both the officers and the crew incurred the same type of sanction, even if in some cases the guilt was aggravated for the officers: thus, as already mentioned, sleeping or abandoning the watch post or not being in order with the uniform always entailed rigorous arrests, while for the lower ranks the sanctions were milder.

Many infractions were expected only due to low strength.

First of all, drunkenness must be remembered and the text is careful to specify that ... no mention is made of the officers, naval guards and cadets while it cannot be assumed that they could be debased to the point of being guilty of such a disagreeable shortcoming.

The same principle also applied to fights. Only midshipmen and sailors were punished for "not keeping their place in order" and "selling items of clothing", shortcomings which could not be attributed to the officers because they had private quarters and paid for the clothing out of their own pockets and therefore they could have.

On the other hand, only the officers and ensigns, who both had their own square at their disposal, were always punished with arrests, even rigorous ones, when they made speeches at the table aimed at disturbing morals or dulling the good regime of the bowl.

Officers were prohibited from smoking on city streets and public places while – if this is not an omission – the lower force was allowed to do so freely and in any case there were no restrictions on smoking on board, apart from the obvious precautions.

A failure that sheds new light on life on board was that committed by those who used the galley to cook or bake something for themselves. Not that it was forbidden, but permission had to be requested from the non-commissioned officer in charge of supervising the service. This habit was probably tolerated in consideration of the monotony of the rations, often insufficient for the appetites of the young people and, who could, supplemented the rations with something purchased on the land or obtained from fishing.

They were punished, even with the public scolding and up to penalty arrests, the officer or non-commissioned officer guilty of using insulting ways or words towards those inferior in rank, especially if aimed at damaging personal honor or that of the country of birth, but naturally it was also forbidden for sailors to utter insulting or offensive words among themselves contempt for service.

Finally, there were also some sanctions that today we could define as "administrative" foreseen for those who had certain tasks: there were fines or withholdings from the salary for those who did not respect the accounting rules, the reports or the keeping of the logbook or ship's documents, or were responsible for errors or delays in the payment of wages. It is obvious that only the small number of those who knew how to read and write could be guilty, starting from the first lieutenant, that is, the second in command and ending with the highest ranking non-commissioned officers.

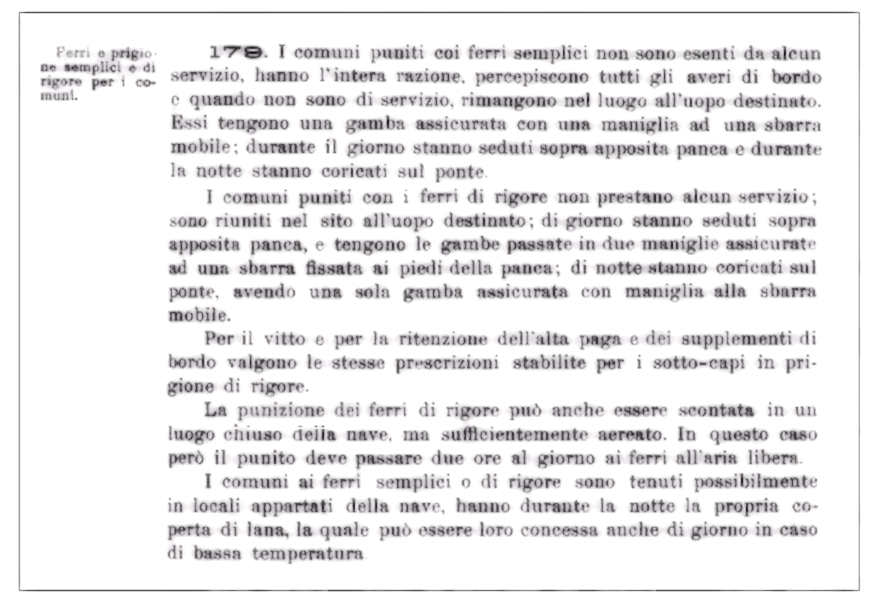

(Methods for the execution of the prison sentence according to the Disciplinary Code of the Royal Navy of 1893)

She was finally considered one gross negligence marriage without permission: for “patented” officers and non-commissioned officers it had to be requested of the King while for the staff of the remaining grades it was informally granted by their superiors. In the first case, the transgression involved a communication to the minister who was responsible for a decision that could lead to revocation from employment while the unfortunate person was placed under arrest pending this.

For the crew there were irons and prison with the addition of the ban on being visited by their women and it should be noted that in this regard the text does not use the word.... "wife" (2).

Read "When discipline was something... serious (part 1)"

Footnotes

1 All ships carried food clerks, representing the supply contracting company, responsible for the conservation and consumption of the products. During the education campaigns, cooks and servants from the Navy Schools also embarked.

2 There were numerous provisions that regulated the marriage of soldiers. The Italian law of 31 July 1871 established that an officer was required to ask the King's permission and demonstrate that he had an income of no less than 2000 or 1200 lire per year depending on his rank. For petty officers, permission was given by the Minister of the Navy and the income had to be at least 400 lire. These incomes could be replaced by an equal amount brought as dowry by the wife and these sums, at the time, substantially corresponded to the wages of a lieutenant and a worker.

Opening image: Punishment in the British Navy during sailing days, inflicted on sailors found guilty of negligence or drunkenness. It consisted of diluting the daily amount of grog (water grog) with six parts of water instead of the normal three. It was a punishment that fell into disuse around the beginning of the 1857th century. Taken from an album of sixty-five works on paper documenting Masters' 1861-XNUMX expedition from England to South East Asia with the Royal Marines, aboard HMS Chesapeake – Author Lt. Col. William Godfrey Rayson Masters RM

(article originally published on https://www.ocean4future.org)