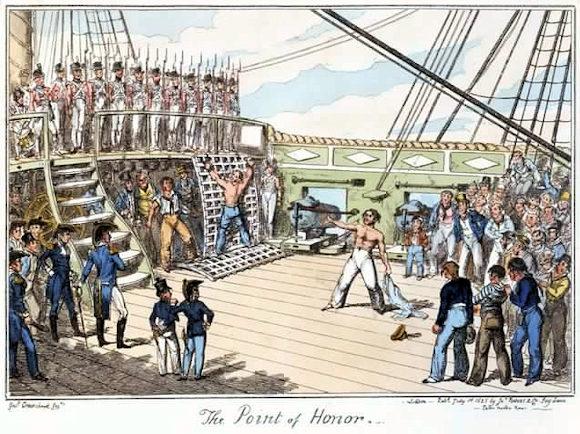

Obviously the title is ironic. Even today in the armed forces certain rules maintain the same inflexibility as always, but at the time of the sailing navy of two centuries ago only a crew bent by a ferocious, almost inhuman discipline, was able to endure the sacrificed life on board, full of dangers, hardships and inconvenience. And beyond this, it should not be forgotten that the crews came from the lowest strata of society and were by nature made up of rough, violent and quarrelsome people.

Perhaps some different considerations could have been made for the officers, but only marginal compared to the general discussion because the quality of life on board and the rules also applied to them, with the added responsibility of maintaining discipline among the sailors.

On Italian ships, in the first half of the 1815th century, a further potential danger to orderly life on board were political ideas: many officers had trained in the Napoleonic era and deep down they were intolerant of the very rigid but outdated rituals and prescriptions that the Restoration of 1 had brought back to life and among the personnel of all levels there was no shortage of those who had joined the secret sects or had become followers of Mazzini (XNUMX).

Cautious openings towards egalitarian ideas, national unity and constitutional governments would only develop in Piedmont shortly before 1848.

In conclusion, at the time (however inhuman) harsh discipline in all its forms was essential to keep hotheads at bay, always dangerous whether they put their hand to the knife or stirred minds with forbidden speeches.

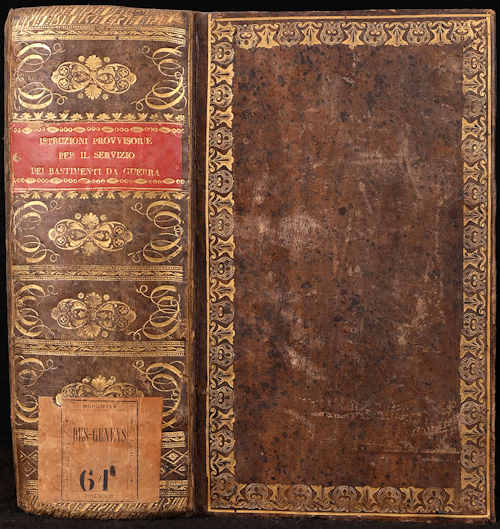

Le “Provisional instructions for the service of warships of the SM Navy” compiled and published in Genoa in 1826 by Admiral Des Geneys, general of the royal armies, admiral, commander in chief of the navy and partly echoing the regulations of the British Royal Navy, among the many topics addressed they also deal with disciplinary regulations, listing in detail in 40 articles with infractions with 29 different types of punishments whose nature and duration varied in relation to the rank held.

For the officers there were:

– Reprimand in private or in the presence of the crew.

– Simple arrests on board.

– Simple arrests in the dressing room or in your room, if on the floor.

– Penalty arrests.

- Suspension

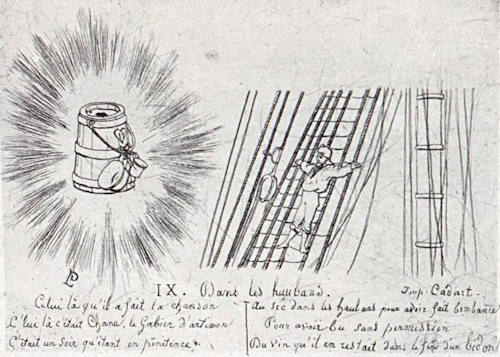

Midshipmen who, at least in some respects, were not considered real officers, received various punishments such as arrests on deck, on spreaders, on cages or on flagpoles. In consideration of the fact that they were staying in a common room with all their peers and that therefore complete isolation was not possible, for the most serious shortcomings the "Lions' Den" had been devised, i.e. …the place that will be designated on board every ship for the punishment of Marine Guardsmen and Cadets, and in which more than one individual will never be detained at a time. The punishment could be aggravated by confinement to bread and water.

A guard was placed at the door to avoid undue visits which, due to youthful camaraderie, it was expected would not be missed.

In any case, it could have been worse: until the previous century, midshipmen could be whipped or beaten while, far from Europe, a similar punishment was suffered in China, even in the last years of the 800th century, by the commander of a gunboat guilty of causing it to run aground on rocks.

For junior officers and sailors the punishments were more imaginative and it was often expected that certain sanctions would be aggravated with the obligation of heavier duty or extension of shifts.

They could incur:

– Wine retention.

– Delivery on board, on the deck or to the barracks.

– Discipline hall or prison according to rank.

– Withholding of wages.

– Grilled (photo).

– To the stocks.

These last two punishments could be aggravated either by short or crossed irons or by food like bread and water.

– Suspension from rank.

And, just for sailors:

– Punishment cap.

– Exposure on the trees from two to four hours a day.

– Class relegation.

– Suspenders, 20 to 60 shots.

– Trenelle, 5 to 15 shots.

The punishments of irons and stocks are well known to those who know history and consist of depriving the offender of mobility, albeit with some periods of freedom during the day and at night (2).

The suspenders and the trenelle are terms to indicate the punishment of flogging: in the first case the leather strip was simple and in the second braided: the suspenders were also provided for the very young enlisted boys aged between twelve and fifteen, who however in such cases they had to be applied "always in a moderate and paternal way".

The flogging could only be ordered by the commander who, in cases where the blows had to be inflicted in a particularly generous measure, had to consult the mate on board and possibly also the pilot and the first helmsman.

The whip was also considered an accessory punishment given in addition to the others in case of aggravating circumstances and which required instant and exemplary punishment; due to the indeterminacy of this statement they could be imposed for any fault without attenuating the other punishments inflicted.

Admirals and senior officers commanding a unit could increase the number of shots up to 180 braces and 45 trenelles.

Admiral Baldassarre Galli della Mantica (Cherasco 1815-1870) gold medal for military valor earned at the siege of Ancona in 1870, but a person with a bad character, was known in the environment for the frequency and ease with which he imposed punishments corporal.

It seems that Admiral Napoleone Canevaro (Lima 1838-Venice 1926) also belonged to the more conservative line, even though he lived in a later era and was able to see a substantial attenuation of punishments.

It was not possible to ascertain what the punishment cap was, which perhaps was above all humiliating and which only brings to mind the headgear with donkey ears with which schoolchildren were punished in a time long gone.

Naturally, what has been said so far on the subject only concerned unpremeditated acts, due to distraction or tiredness, while if the event required it, it was passed to the judgement, which could have been much more severe, of the Maritime War Council (3).

Footnotes

- Even Giuseppe Garibaldi, who enlisted in the Sardinian Navy in 1833 and embarked on the frigate Euridice, confesses in his memoirs "my mission there was to make proselytes to the revolution and I had disengaged myself from it in the best way".

- The punishment of irons survived for a long time even after the abolition of other corporal punishments which occurred, at least formally, in all European navies shortly after the mid-1937th century. The “Regulations of discipline for the indigenous soldiers of the Royal Colonial Troops Corps” of XNUMX still provided for the punishment of stocks for them.

- On the basis of the Military Penal Code, the War Councils had the power to sentence people to imprisonment for up to twenty years, to forced labor which could even be for life, to beatings with the rod (up to eighteen hundred!) and in the most serious cases to time of war to death with a noose on the gallows or being shot in the back.

* was born in Broni (PV) in 1951. Having graduated in law, he was an officer of the Port Authority and subsequently an official of a public body. He has nine books to his credit including "History of the Port Authorities", "Two thousand years of Po Valley navigation" and "The anchors and the tiara - The Pontifical Navy between Restoration and Risorgimento" and over 400 articles concerning history, economics and transport . He collaborates with numerous specialized periodicals including the Rivista Marittima”.

Photo: web

(article originally published on https://www.ocean4future.org)