Anyone who has kept an eye on the renewal of the Navy ship (limiting the analysis to "gray ships", ie combat ships, and excluding the auxiliary ship) cannot fail to have noticed that since the launch of the Cavour (in the opening photo in the background), in 2004, the displacement of ships increased dramatically.

The aircraft carrier cruiser Cavour, displacing 27.000 tons, went alongside the Giuseppe Garibaldi, of just 14.000 tons. The two old class destroyers Boldness, dating back to the early 70s and displacing approximately 4.500 tons, were replaced with those of the class Horizon, of 7.000. The slightly later classes of frigates Wolf e Mistral, of 2.500 and 3.000 tons respectively, are being replaced (some Mistral are still in service) with the Bergamini, from 6.900 tons. The offshore patrol boats of the classes Cassiopeia, Sirio e Commanders they will be replaced by the Multi-Purpose Offshore Patrol boats of the class Thaon of Revel and, much later, by the EPCs (European Patrol Corvettes): ships of around 1 tons will be replaced by vessels of 500 and 6.000 (theoretical value given that the EPCs are still in the planning stage) tons respectively.

Finally, the class destroyers Durand de la Penne of 5.400 tons will be replaced by future DDX which, as far as is known, will displace 11.000 tons. In short: in a few years the Navy will not have any ships below 3.000 tons of displacement, except for coastal patrol boats and support ships for COMSUBIN raiders.

The tendency towards gigantism is inherent in the evolution of the navy: from the ancient triremes that became quinqueremi to the medieval galleys that evolved into galleys and galleons, from sailing vessels with an ever-increasing number of decks to armored ships that became giants of the sea such as the Yamato or Iowaalways, throughout history, the new generation of ships has been larger than the previous one. All time. But all of them, once they reached the pinnacle of their development if not earlier, were defeated by smaller means.

In 1588, when Ferdinand II of Spain's "Invincible Armada" attempted to land in Elizabeth I's England, the great Spanish galleons were defeated (with the help of storms, of course) by small and nimble English vessels.

When, on the threshold of the Great War, single-caliber battleships became the backbone of the great European navies, torpedo boats were designed, small ships armed almost exclusively with torpedoes, so threatening that destroyers had to be invented to protect the fleet from their attacks.

Later came the torpedo boats: every year the Navy celebrates its party on June 10, the anniversary of thePremuda company, when two "walnut shells" called MAS (Motoscafi Armati Siluranti), displacing about thirty tons and with ten crewmen, sank the St. Stephen, Austro-Hungarian battleship of 20.000 tons and over a thousand crewmen.

In the subsequent conflict, the large battleships were sunk by "half-ships" of a few tons and of one, maximum three crewmen called planes: Yamato, Bismarck, Prince of Wales were sunk (or in the case of the Bismark, sentenced to death but not yet finished) from airplanes, not counting the ships victims of the Taranto night or the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Despite these lessons, gigantism continued into the Cold War as well. To remain within the Navy, the destroyer classes that followed were: Fante (ex-class Fletcher US, 3.100 tons), Gunner (ex-classes Benson e gleaves US, 2.600 tons) Indomitable (2.500 tons), Fearless (4.000 tons), finally the already mentioned Boldness (4.500 tons) e De la Penne (5.400 tons).

The growth of displacement, as can be seen, has been there, but it has been slow, as it had been in previous decades and centuries. With the 2000s, it underwent a sharp acceleration: in many cases the generational leap led to a net doubling of the tonnage.

But why? At the base of the naval gigantism of the past there was a simple need: the increase of firepower. Trivially, a larger ship meant guns of greater caliber (or, in ancient times, more men for boarding and more mass for ramming). However, the principle came to an end with the arrival of the planes and, later on, of the anti-ship missiles.

In the vast majority of Western navies and not only the anti-ship missile is always the same, whether it is fired from a corvette or a cruiser: Otomat, Harpoon (photo) ed Exocet they are embarked on any ship designed for combat, and in the latter two cases a modified version of the same weapon is also launched from airplanes and submarines. In these conditions, the difference in power is no longer given by the size of the weapon, but by the number.

In the vast majority of Western navies and not only the anti-ship missile is always the same, whether it is fired from a corvette or a cruiser: Otomat, Harpoon (photo) ed Exocet they are embarked on any ship designed for combat, and in the latter two cases a modified version of the same weapon is also launched from airplanes and submarines. In these conditions, the difference in power is no longer given by the size of the weapon, but by the number.

One would therefore think that our new ships have been designed to carry a greater quantity of armaments. Unfortunately, this is not the case, as these comparison tables can demonstrate. Let's start with the aircraft carriers.

Already from this first table it emerges that an increase in displacement is not matched by a proportional increase in military capabilities: Cavour displaces almost double the Garibaldi (more than double if, of the latter, the displacement is considered before the modernization works), but this does not mean that it has double the number of aircraft. The Cavour it benefits from the fact that it was designed from the outset to operate with fixed-wing aircraft, therefore it can accommodate aircraft in the open, on the flight deck, as well as in the hangar, increasing the number of aircraft transported to thirty. Not so the Garibaldi, which was born as a helicopter carrier and was modified during construction, so the question arises: what if it too had been designed with the same criteria? How many aircraft could it have carried?

To have a yardstick, the Spanish Prince of Asturias, just prior to Garibaldi and with a displacement of 17.000 tons, it was capable of carrying a maximum of 29 aircraft and embarked 4 anti-aircraft defense systems Meroka, but it had no missiles.

Il Cavour, with 10.000 tons more, it has a similar flight department (as long as a dozen aircraft are left in the open), but greater defense capabilities. It is clear that the increase in displacement was not exploited properly and that a smaller ship would have had comparable capabilities.

Let's now turn to the destroyers.

Even taking into account technological advances (such as the increase in the rate of fire of the 76/62), it is clear that the Horizon they have one even lower firepower than their predecessors: the 76/62 has gone from 4 to 3, the 127mm has disappeared, making these ships unable to fire against the coast. The real novelty is represented by vertical launch systems (VLS), capable of hosting anti-aircraft missiles Aster 15 and 30. In themselves these weapons are much more performing than the previous ones Asp e Standard SM-1, moreover there is a greater number ready to launch: the Mk13 could launch only one missile and then had to be reloaded, the Albatros could launch 8. Instead, the 6 VLS modules of the Horizon, if used fully, they allow to have 48 missiles ready to launch.

The VLS seem to be more bulky (at least as regards the space occupied on the deck) than the previous systems; therefore, one might think that the increase in displacement served to house these weapons. We will see later how this reasoning is completely fallacious.

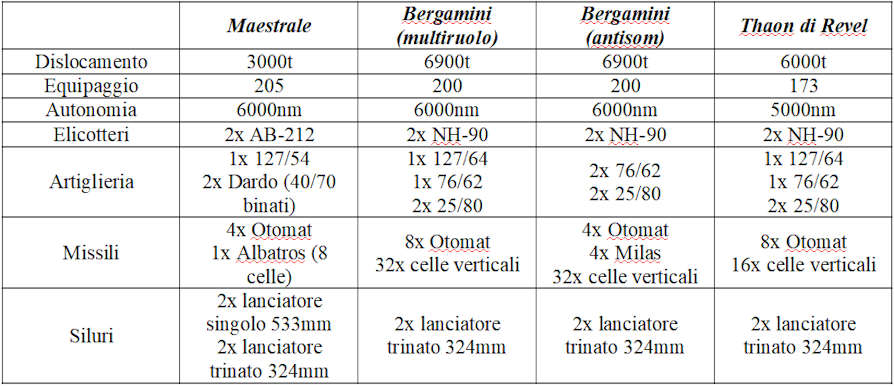

We continue with the frigates, using the class Mistral as a touchstone and taking into account both versions of the class Bergamini.

In the case of frigates, it can be said that the class Bergamini has firepower equal to that of the class Mistral. Also here it is worth noting the adoption of vertical cell launchers, which has increased anti-aircraft capabilities. However, doubling the displacement is not accompanied by an increase in firepower. Indeed, the class Bergamini was judged unable to simultaneously fill the roles of anti-aircraft escort / anti-ship attack and that of anti-submarine escort, leading to the division into two subclasses, or variants, almost identical in terms of armament, but with great differences in the field of electronics.

You may have noticed that PPAs have also been included in the frigate table. This is because it is impossible to compare the Thaon of Revel with the patrol vessels they will replace: the latter were armed only with artillery and a helicopter, while the PPAs will also have anti-ship and anti-aircraft missiles.

In fact, despite the name, the PPAs (photo) are real frigates, with a panoply almost identical to that of the Bergamini in multi-role version (at least in the Full, level to which even the versions can be brought in a short time Light e Light +).

In fact, despite the name, the PPAs (photo) are real frigates, with a panoply almost identical to that of the Bergamini in multi-role version (at least in the Full, level to which even the versions can be brought in a short time Light e Light +).

We close this review with the latest data: the recently launched Trieste it should replace one of the class amphibious ships St. George.

Il Trieste, with its 36.000 tons of displacement, is capable of carrying 605 men in addition to its crew, a ship of the class St. George, with 8.000 tons, 350.

From these comparisons it is evident that the increase in displacement did not lead to an increase in firepower or in the carrying capacity of aircraft and men.

An exception is the anti-aircraft defense with the VLS, which, we said, can be seen as one of the causes of the increase in the size of the ships. But the reasoning doesn't hold up, as ships of similar size can carry more weapons.

Let's consider the US class destroyers Arleigh Burke and cruisers Ticonderoga (the second version, equipped with VLS) and let's compare them with the Italians Horizon and future DDX.

Taking into account that American ships were launched in the 80s, it emerges again that Italian ships do not adequately exploit their size.

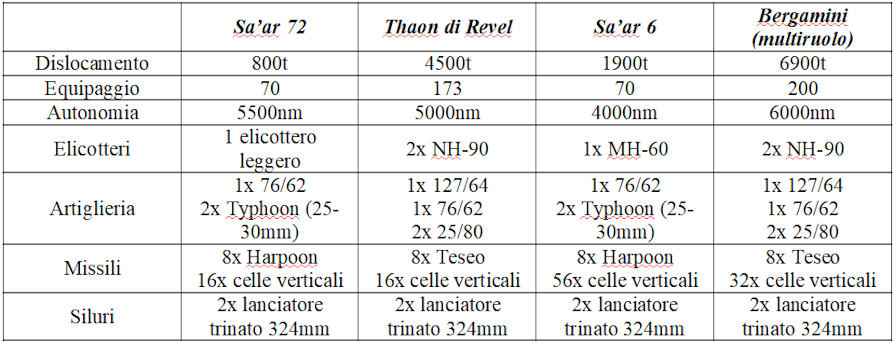

The picture becomes even more bleak when much smaller ships are considered, which are still capable of carrying an equal or greater number of missiles. Just think of two classes of Israeli ships, the Sa'ar 6, in progress, and future Sa'ar 72.

Except for the helicopters and the absence of a 127mm gun capable of shooting against the coast, it is possible to note that the class Sa'ar 72, weighing just 800 tons, it will perform almost equivalent to the Thaon of Revel in version Full and higher than the version Light, both of over 6.000 tons. The comparison between the class Sa'ar 6 of 1.900 tons and the class Bergamini of 6.900 tons, then, is merciless. Unless the frigates Bergamini do not carry 16 Aster 30 missiles in the first two VLS modules and light missiles capable of being arranged in groups of 4 in each single cell such as CAMM or CAMM-ER, thus having 64 other missiles, Italian ships are outclassed by Israeli ones with their 16 Barak-8 and 40 C-Dome, which play the same role as the Aster 30 (medium / long range air defense) and Aster 15 / CAMM (short range air defense) respectively. And this despite the fact that Italian ships displace 5.000 tons more.

To sum up, all the military ships launched in the last twenty years and also the future one have exaggerated dimensions and an inadequate panoply of weapons. And the data we have reported are those with the ships at their maximum capacity: in reality the Horizon (photo) at the moment they travel with only 4 VLS modules (36 cells), the frigates Bergamini with 2 modules (16 cells) and have never been certified for the launch of Otomat. This is an obvious design error.

To sum up, all the military ships launched in the last twenty years and also the future one have exaggerated dimensions and an inadequate panoply of weapons. And the data we have reported are those with the ships at their maximum capacity: in reality the Horizon (photo) at the moment they travel with only 4 VLS modules (36 cells), the frigates Bergamini with 2 modules (16 cells) and have never been certified for the launch of Otomat. This is an obvious design error.

Still, the mistake is absolutely deliberate. The reason lies in autonomy. Not so much that, strictly numerical, of the nautical miles that can be traveled which, as you can see from the tables, do not vary much; as much as that of ergonomics or, to put it more simply, of comfort. The new ships offer cabins for two people, which can be increased to three or four, even at the last of the sailors, with all the necessary comforts, instead of the "bunks" and "berths" (the names speak for themselves) of the past. . Even the eating areas have changed: if in the Cold War ships the sailors ate in the corridors on retractable tables hooked to the wall, now they have real canteens. These comforts derive, on the one hand, from the fact that now the Armed Force is made up of professionals and no longer conscripts, and therefore must "treat better" its men; on the other hand, the Navy plans longer missions, in more distant places.

This trend is the result of the theory of the "enlarged Mediterranean", which prompted the Navy to increase its range of action. It should be added that for the Navy (and not only) the watchword, in recent decades, has been "projection of force" (or power, if you prefer), that is (in the most general terms possible) the ability to "acting" (even by force) very far from their starting points. Also for this reason, all the Italian ships launched in the XNUMXst century were designed from the outset to be able to carry a certain number of marines from the "San Marco" regiment and to deploy them by helicopters or rafts.

Last but not least, ships like the Cavour (photo) have been designed for "dual use" purposes, dedicating spaces otherwise usable to instrumentation for the rescue of populations.

Last but not least, ships like the Cavour (photo) have been designed for "dual use" purposes, dedicating spaces otherwise usable to instrumentation for the rescue of populations.

All this requires, with the same weapons, crew and supplies on board, much greater spaces than the more Spartan ships of the Cold War, leading the Navy to launch ships capable of competing in tonnage with those of the major world navies without a proportional increase in their military capabilities and to lose the ability to cope with its primary task: the defense of trade routes.

As the Second World War has amply demonstrated, the Italian naval war is, and always will be, a war for trade routes. And this requires a "battle team" capable of delivering strategic blows and defending the country from similar enemy attacks, but also, and above all, a large number of light units, the "thin ships", cheap to to build and to maintain, which materially accompany merchant ships on their journeys and defend them from all threats, be they other surface ships, airplanes or submarines. This task has become even more complicated with the appearance of remotely piloted aircraft and ships, including underwater ones. To face such threats, close and continuous surveillance is needed, something that our new ships, huge, expensive and, above all, few, will not be able to guarantee.

Fascist Italy made exactly the same mistake, letting thin ships age (torpedo boats and destroyers at the time) and focusing on the production of large battleships (battleships and cruisers). Eventually, the mistake was understood and they tried to run for cover with the launch of the class corvettes Seagull, but it was definitely too late. And although the then Royal Navy did an excellent job, he paid a very high toll for his strategic mistake.

"Regional power with global interests", this is the geostrategic definition of Italy. To put it simply, a "small country with big interests", but "big interests" must not make us forget the first part of the definition: "regional power", "small country".

Italy is not the United States of America, which can operate all over the world taking for granted (or almost) the safety of the water at home. In the event of a "symmetrical" conflict (and the war in Ukraine has made it clear that this risk still exists today, with all due respect to the deluded optimists that history had ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall) the Italian naval war would be fought in the Tyrrhenian Sea, in the Strait of Sicily, perhaps in the Adriatic, or between the Aegean islands, in general in the "narrow" Mediterranean. Even assuming that our fleet is called to operate in the Indian Ocean or the Pacific, it will always be a more or less small team that will operate in cooperation with other allied teams starting from allied bases.

The ships "too big", even when well designed (which the current ones, as we have seen, are not), are useful to us, but that does not have to be the backbone of our fleet, this role belongs to the "small ships".

The ships "too big", even when well designed (which the current ones, as we have seen, are not), are useful to us, but that does not have to be the backbone of our fleet, this role belongs to the "small ships".

To conclude, a hundred years ago Paolo Thaon di Revel (photo), the admiral to whom the PPA class leader is named, at the end of the First World War (we emphasize: the First), had understood that the Italian Navy had to be formed by a small battle squad and a large number of smaller ships and a strong navy aviation, because that was what the Great War had shown.

Twenty years later, the ensuing conflict proved how right he was.

We intend to wait for the third failure or we decide to learn from our mistakes?

Photo: US Navy / Navy