On that moonless night, with engines off to avoid being intercepted, the young commander of the PT-109 torpedo boat found himself in an absolutely absurd kinematic situation. He was part of a group of 15 torpedo boats led by the lt. comdr. Thomas G. Warfield who, in hindsight, had handled the mission in an amateurish manner.

The group had been sent patrol and interdiction mission into the Blackett Strait, via the Ferguson Pass, along the Japanese supply routes of the code-named route Tokyo Express.

An intelligence report had reported that five enemy cruisers would sail that night from Bougainville Island, across the Blackett Strait, to Vila, and the torpedo boats went out to intercept them, taking advantage of the night hours. The attacks were unsuccessful, indeed they were somewhat clumsy.

During the mission eight torpedo boats launched 30 torpedoes without being able to hit any target.

Among other things, from the examination of the operation orders, there was not even an emergency procedure in the event that one of the PTs was hit. In practice, the torpedo boats received the order to launch the two torpedoes supplied and then return to the base. In fact, that was what happened: the boats equipped with radar fired their torpedoes first and left without supporting the rest, such as the PT-109, which were left without radar assistance and were not informed that other units had already engaged in combat. the enemy. So three torpedo boats, PT-109, PT-162 and PT-169, continued to patrol to optically intercept the enemy.

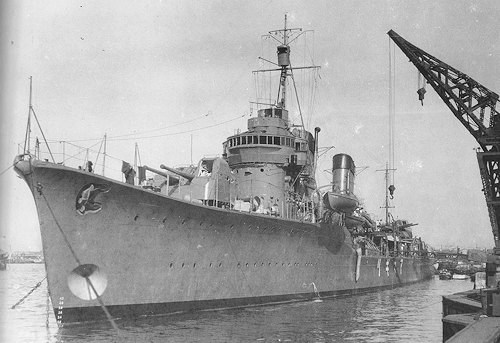

At around 02:00 am on August 2, 1943, a moonless night, the PT 109 turned off the engine to prevent Japanese aircraft from detecting the wake. Suddenly they realized they were on the route of the Japanese destroyer Amagiri (photo), who was returning to Rabaul. The PT-169 launched two torpedoes at theAmagiri (which failed) while the PT-162 could not even get them started and drove away. The PT 109 did not have time to start the engine and was rammed by the Japanese destroyer who was proceeding at over 23 knots.

At around 02:00 am on August 2, 1943, a moonless night, the PT 109 turned off the engine to prevent Japanese aircraft from detecting the wake. Suddenly they realized they were on the route of the Japanese destroyer Amagiri (photo), who was returning to Rabaul. The PT-169 launched two torpedoes at theAmagiri (which failed) while the PT-162 could not even get them started and drove away. The PT 109 did not have time to start the engine and was rammed by the Japanese destroyer who was proceeding at over 23 knots.

The 109 was hit on the starboard side at a 20 degree angle, and the impact severed a piece of the boat. After the war, the commander of theAmagiri, Lieutenant Captain Kohei Hanami, admitted that the ramming was intentional, favored by the situation. The following hours underlined how the mission had been badly managed by Commander Warfield, who had delegated to the young commanders how to manage everything, not even providing for any procedures to search for survivors in the event that a ship was lost.

Ship captain Robert Bulkley, a naval historian, wrote that this was perhaps the most confusing and least effective action performed by patrol torpedo boats. Eight PTs launched 30 torpedoes to no avail.

When the PT-109 was rammed around 2:27 am, a column of fire 30 meters high was generated, and the fuel spilled into the sea, causing a fire in the surrounding waters. Two sailors, Andrew Jackson Kirksey and Harold William Marney, were killed instantly and two other crew members were seriously injured and burned, falling into the burning sea surrounding the torpedo boat.

The commander managed to save MM1 (1st class engineer, ed) Patrick McMahon, the crew member with the most serious injuries, which included burns that covered 70 percent of his body, and carried him to the bow that was still floating. Then he threw himself back into the water saving two others. The eleven survivors clung to the bow section of the PT-109 for twelve hours as the floating wreck drifted, slowly heading south.

At around 13:00 pm on August 2, the hull began to take on water and the captain realized that it would soon sink. He then decided to swim to a tiny desert island. He was called Plum pudding, but the men called her “Bird Island" because of the guano that covered the bushes. Not everyone was able to swim with dexterity, indeed some did not know how to do it, and they placed a lamp, shoes and… “the non-swimmers”… on one of the floating beams, starting to push it towards the island.

The commander, who had been on the Harvard University swim team, used a life jacket strap gripped between his teeth to tow the most seriously injured sailor.

However, it took four hours to swim to the island, about three miles away, between treacherous currents and the constant fear of being attacked by sharks, attracted by the blood of the wounded.

The island was only 91 meters in diameter, and provided no chance of survival, that is, neither food nor water. The exhausted crew trailed behind the tree line to hide from the passing Japanese barges. On August XNUMXth they moved, swimming nearly four miles, south of Olasana Island, battling a strong current, where they found ripe coconuts, even though there was no drinking water.

The island was only 91 meters in diameter, and provided no chance of survival, that is, neither food nor water. The exhausted crew trailed behind the tree line to hide from the passing Japanese barges. On August XNUMXth they moved, swimming nearly four miles, south of Olasana Island, battling a strong current, where they found ripe coconuts, even though there was no drinking water.

The following day, August 5, Commander and Ensign Ross swam for an hour to Naru Island, where they found a small canoe, packets of crackers and candy, and a fifty-gallon can of drinking water left by the Japanese. .

On the island of Olasana they met some Melanesian observers with whom the young commander was able to exchange a few words and, above all, to convince them that they were Americans. They brought some sweet potatoes, vegetables and cigarettes from their pirogue and helped the exhausted crew until help arrived two days later.

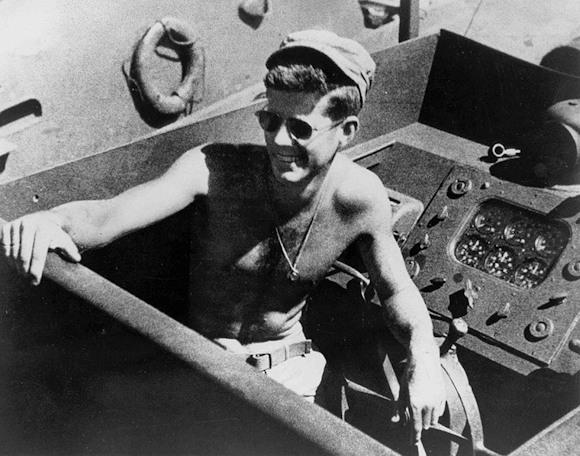

Now you may wonder what is special about this story ... Many minor events like this happened during the war but the particular thing was that that young commander would one day become the president of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

A brave officer

John F. Kennedy, despite having health problems in his back, thanks to the help of Captain Alan Kirk, director of theNaval Intelligence Office (ONI), who had been a naval attaché in London when his father, Joseph P. Kennedy, was the ambassador, was drafted into the US Navy and was appointed reserve midshipman in October 1941, joining the staff of theOffice of Naval Intelligence.

Kennedy took the complement officer course with the Naval Reserve Officers Training School (NROTC), at Northwestern University, from July to September 1942, and after graduation he was awarded the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Training Centre based in Rhode Island. In December he was appointed commander of the PT-101 torpedo boat, belonging to the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron FOURTEEN, deployed in Panama.

At the outbreak of World War II, Kennedy applied to be assigned to the area of operations and, the following month, was assigned to command the PT-109 in the Solomon Islands.

During a combat mission, as I mentioned in the first part, it was sunk by the Japanese destroyer Agimari, but he managed to save almost all the members of his crew.

For his behavior, Kennedy was later awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for rescuing his crew, eventually earning the Purple Heart for injuries sustained in combat.

Kennedy returned to the United States in January 1944, but due to back problems he had to retire from the Navy reserve due to physical disability in March 1945 with the rank of lieutenant.

Nonetheless, Kennedy remained intimately linked to the US Navy and, in August 1963, he wrote "Any man who may be asked in this century what he did to make his life worthwhile, I think can respond with a good deal of pride and satisfaction, 'I served in the United States Navy,'".

The USN did not forget this by naming one of its aircraft carriers, CVN-79, after him.

(article originally published on http://www.ocean4future.org)

Photo: US Navy / web