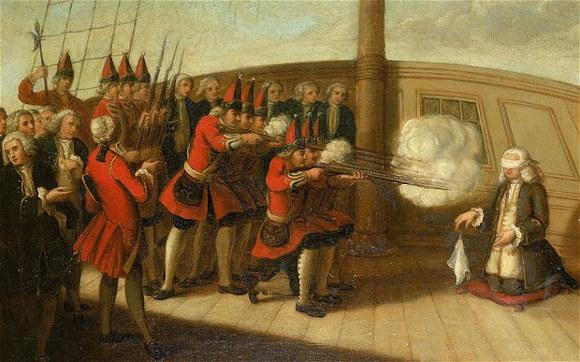

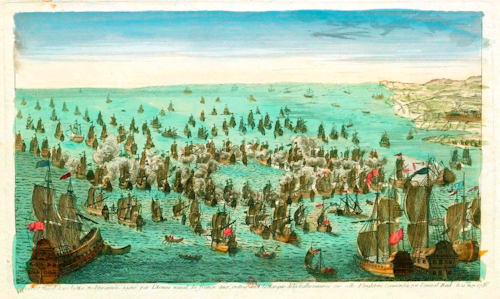

On 14 March 1587 the Honorable John Byng, Admiral of the Blue, was shot by a firing squad of nine Royal Marines on the quarterdeck of HMS Monarch anchored at Spithead. Byng's execution probably constitutes the single most important decision in the institutional history of the Royal Navy in the 18th century: an event destined to have a lasting influence on the evolution of the navy's command style, conduct of operations and tactical thinking British until ideally arriving at the Nelsonian "engage the enemy more closely", the last signal transmitted to Trafalgar before the start of the close-range clash with Villeneuve's combined Franco-Spanish fleet.

Byng had been placed under arrest after returning home following the failure of the relief expedition to Menorca and then tried on the basis of the alleged violation of the twelfth of Articles of War1, imposing the death penalty on anyone found guilty of withdrawing from action, or failing to engage in battle, through cowardice, negligence or disaffection for service; although the wording of this charge seems to allude to the admiral's very lackluster conduct during the clash with the French squadron of La Galissonière off the island, Brian Tunstall deserves credit for being the first to have argued conclusively how Byng's conviction had little or nothing to do, in truth, with the outcome of the battle of Minorca; and much, on the other hand, with the patent transgression of the orders received, of which the admiral had been guilty since his stopover in Gibraltar on 2 May 1756.

Informed in fact that not only had the French already taken land, but that St. Philip's Castle was actually besieged by the 15.000 men of the Duke of Richelieu, already despairing of the success of the mission, he had willingly allowed himself to be persuaded by the lieutenant General Thomas Fowke, commander of the Gibraltar square (determined not to give up even a man of his command at that time), to convene a council of war in which unanimously ruled that nothing could be done to save Minorca. Byng had therefore decided not to embark that battalion, among the four stationed in Gibraltar, which his orders expressly commanded him to attempt to introduce into the square of Minorca in the event of a siege. And he had communicated this decision promptly and recklessly to London!

On this occasion he declared, in his communications to the government, that he would still set sail for the island, in order to be an impartial judge of the situation of the garrison. Once there, once again, he failed to comply with the orders he received.

On this occasion he declared, in his communications to the government, that he would still set sail for the island, in order to be an impartial judge of the situation of the garrison. Once there, once again, he failed to comply with the orders he received.

A half-hearted attempt to establish a connection with St. Philip's Castle, on May 19th, went up in smoke as soon as the French team appeared on the horizon, which Byng had immediately started hunting by concentrating all available forces. It would be the first and last effort made by the admiral to personally ascertain the state of Blakeney and himself inside the besieged fortress. After the serious damage suffered by the ships of his vanguard during the battle of the 20th, he once again convened a war council and, carefully maneuvering the opinions expressed by presenting a series of tendentious questions about the slim chances of alleviating the conditions of the besieged , once again that assembly expressed itself unanimously on the impossibility of providing any assistance to the besieged of St. Philip's Castle. Once again the admiral sent reckless communication of this resolution to London, so much so that Tunstall is at ease in illustrating how those two despatches, once received by the Newcastle cabinet and the king, had the effect of a bomb, marking ever since Byng's fate.

Le Fighting Instructions they did not speak of sieges to be raised or garrisons to be relieved, nor did they prescribe penalties for failure to comply with such instructions; which is why it was decided - through a convenient legal aberration - to sentence Byng to death for a crime he had not committed, but which was contemplated by Navy regulations, so that he was punished for the shortcomings of which he was guilty, but of which he was not prosecutable under the law.

For further details on the story and its implications, please refer to my review of Brian Tunstall, Admiral Byng and the Loss of Minorca, London: Philip Allan & Co., 1928, published in Issue 11, Year 3 (June 2022) of New Military Anthology; a book which, ninety-six years after its first publication, remains the most important contribution on the battle of Minorca and Byng's trial events which ended in such a dramatic way.

Personally, I will never tire of underlining that, although the historiographical conclusions reached in their respective works by the founding fathers of British naval history, the various John Knox Laughton, Herbert W. Richmond, WCB Tunstall, Julian S. Corbett, are obviously questionable and have actually undergone a profound revision in the meantime (an example of this is the interpretation, recently overturned by Richard Harding in all its salient points, that Richmond offered in 1920 of the failure of the siege operations of Cartagena de Indias in 1741) , the general principles expressed through the analysis of individual historical cases by these authors still constitute an integral part of modern theories of maritime power, therefore making knowledge of the historical works of that period and that generation of lasting importance.

Again, by way of example, what kind of dilemmas suspended between instances of rigid centralization of command promoted by modern communication technologies, and freedom of initiative necessarily devolved to commanders engaged in action according to the best Nelsonian tradition, did authors like Corbett try to address? in transparency of their historiographical works, has been effectively underlined by fundamental works of modern naval history such as The Rules of the Games by Andrew Gordon and, more recently, by Andrew Lambert's superb intellectual biography of Corbett (The British Way of War, Yale University Press, 2021).

1 12th war article as reported in Byng's defence, pg. 10 of CM “Every Person in the Fleet, who thro' Cowardice, Negligence or Disaffection, shall in Time of Action withdraw, or keep back, or not come into the Fight or Engagement, or shall not do his utmost to take or destroy every Ship which it shall be his Duty to engage; and to assist and relieve all and every of his Majesty's Ships, or those of his Allies di lui, which it shall be his Duty di lui to assist and relieve, every such Person so offending and being convicted thereof by the Sentence of a Court Martial , shall suffer Death.”

Photo: web

(article originally published on https://www.ocean4future.org)