In the colonization of Australia (particularly in New Wales) there were not only male deportees, but also young women from English prisons.

It all began when the English Crown decided to deport low-cost labor from the overcrowded English prisons in the decade between 1770 and 1780 for the urbanization works and cultivations of that new immense territory where they would be employed in forced labor until the end of the their pain.

In reality, after having paid their debt to justice, their return to their homeland was far from guaranteed and the motherland would hardly have welcomed their return. A Columbus egg: low-wage workers and then settlers, repaid with lands to be exploited and whose proceeds would be returned in the form of taxes to the Crown!

But, as we know, the work would not have been complete without a female presence. Taking advantage of the voices of public opinion, scandalized by the brutal treatment reserved for female prisoners often convicted only of thefts and vagrancy, the Crown accepted the request of the governor of New Wales, Lord Sydney, to have some girls transferred from the overcrowded Newgate prison to Australia . In practice, the prisoners were offered an attractive alternative: to be deported to the new world, where they could start a new life, or... to die in her Majesty's prisons. A practical solution that convinced, more or less spontaneously, the then 151 girls imprisoned in the prison to accept the proposal.

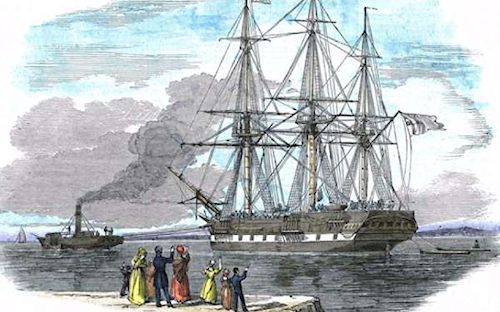

Thus it was that a ship, the Lady Juliana, placed under the command of an able captain, Aitken, and assisted in this particular task by Lieutenant Thomas Edgar, an elderly and experienced officer who had participated in James Cook's exploration voyages who had the task of ensuring that the terms of the contract were respected and that prisoners were "adequately" cared for.

Among the staff, the ship's surgeon, Richard Alley, should be mentioned, a doctor who proved to be extraordinarily competent compared to the standards of the time. It was precisely thanks to Alley's attention to the hygienic aspects to be maintained during the transfer that the journey was "successful": from the improvement of the on-board diet, introducing vegetables and fruit, to an adequate supply of soap, sheets and blankets to improve the hygiene of the "passengers", among whom there were some who were pregnant. Captain Aitken himself was an unusually tolerant commander compared to his colleagues in command of subsequent convict transports to New South Wales (Second Fleet). According to reports released by John Nicol, ship's steward Captain Aitken, “He was an excellent person and did everything in his power to make the inmates feel comfortable”.

The preparation for the trip was thorough and the availability of space allowed us to sit on the Lady Juliana other young women detained in other prisons for a total of 245 prisoners.

In fact, on July 29, 1789, after a six-month delay, the Lady Juliana it finally set sail from Plymouth on a voyage that would last 309 days when, after many stops, it arrived in Botany Bay on 6 June 1790. A longer voyage than those made by ships of the same type, in which the vessel made numerous stopovers including Tenerife , St Jago, forty-five days in Rio de Janeiro and nineteen days at the Cape of Good Hope.

A transfer which, considering the standards of the time, was in a certain sense fortunate as only one sailor died, who fell overboard during a storm. Of the inmates one died of a broken heart before departure and four were pardoned1. In practice, even if we wanted to include them in the "cargo" count, the loss was negligible (if not zero) considering that the deportation from the United Kingdom to Australia was generally considered a real decimation for the inmates who often died from malnutrition, epidemics , and mistreatment.

In fact these ships (in particular those of the infamous Second Fleet, in charge of the transfers of prisoners) were normally entrusted to commanders with few scruples who, having maximum freedom in managing the budget assigned to them, did not disdain to supplement their emoluments to the detriment of the "passengers"; the latter, when they succumbed, were thrown into the sea with percentage losses upon arrival of 50% of the total number2.

In the case of Lady Juliana, the deportees, a good number of whom were young girls of low rank, convicted of crimes against property or prostitution, were decidedly luckier; they enjoyed a certain freedom on the ship which included the possibility of roaming freely on the decks and engaging in relationships with the crew members (with whom they are said to have had more or less consensual relationships). According to shipboard documents, there were only six new cases of pregnancies on board, probably because the older ones had instructed the younger ones to use the rudimentary contraceptive methods of the time.

Punishments were rare, among them that of a beating...

Punishments were rare, among them that of a beating...

During the journey the ship stopped at various ports to stock up on food, drinking water and anything else needed. Edgar made it clear to the passengers that the budget was very limited and that, before the end of the trip, they would have to be subjected to several deprivations, unless they were willing to earn more money by prostituting themselves. This happened not only with the crew but also in the ports that the ship called. Needless to say, the prospects were not very attractive, so the deportees offered themselves to these services. In practice it became a "floating brothel" as cited in the essay of the same name by Welsh historian Siân Rees.

According to the documents found, in reality, the income linked to this activity was actually spent to improve life on board and not to enrich Commander Edgar's coffers. The ship's steward, John Nicol, wrote a fascinating account of the voyage in which he recounted details of life on the ship: “when we were far enough out to sea, every man on board took a wife from among the convicts, not repugnant."

Sailors from other ships were welcomed freely in the ports of call, and the officers made no attempt to repress this licentious activity. Edgar, as mentioned, had acquired a lot of experience in his voyages with Cook and was, like the ship's doctor, an advocate of James Lind's theories on the need to supplement the on-board diet with large quantities of plant foods to avoid the bête noire that afflicted the sailors during those long voyages: scurvy. In fact it worked and good hygienic management allowed young women to be delivered to the new southern world in relatively good health.

Rations were distributed adequately and there was a certain amount of care taken to keep the internal rooms clean and fumigated; but not only that, the prisoners were given free access to the deck and in the ports of call the ship was always stocked with fresh food. A treatment in stark contrast to that reserved for the other ships of the Second Fleet, who arrived at their destination with a shameful "load" of starving and mistreated prisoners.

Of course, upon their arrival in Botany Bay, in June 1790, the girls found themselves faced with a new continent, a life that was certainly not easy but certainly better than the one they had left at home. The most attractive married some former deportees who had remained in Australia having made their fortune by cultivating or breeding animals in the vast lands made available to them.

They too deserve credit for the success of this wonderful country, on the other side of the world.

1 According to Nicol (op. cit., chapter 9) “One, a Scottish girl, broke her heart and died in the river. She was buried at Dartford. Four were pardoned on account of his Majesty's recovery of him.."

2 According to sources at the time, the other ships that arrived in the same month as the “Lady Juliana” at the Sydney base, which included Port Jackson and Botany Bay, carrying only male deportees, had lost between 200 and 400 passengers on the voyage and the few survivors were in desperate conditions.

Images: OpenAI / web

(article originally published on https://www.ocean4future.org)