As we have seen in previous article simulations in the defense field are aimed at achieving these 4 objectives:

A - The training of military personnel

B - Research and development of winning strategies/tactics in known scenarios

C - The definition of the characteristics of new systems

D - The validation of new systems

We try in this article to have an overview of the activities of modeling and simulations effectively carried out in Italy and abroad and aimed at the objectives listed above.

The national scenario

In Italy, the three armed forces all have a reference simulation centre.

THEArmy has equipped itself with Army Simulation and Validation Center (Ce.Si.Va., Ref. 1) of Civitavecchia in 2004, taking on the legacy of other previous structures (the SIAT project, Integrated Land Training System, took its first steps in 1999). It allows broad spectrum simulations (Constructive, Virtual and Live) and is mainly focused on training (objective A reported at the beginning of the article)

Constructive-type simulations are based on the commercial product COTS Joint Conflict and Tactical Simulation (JCATS). This product allows real-time simulation and is based on a DIS-HLA architecture. It is exercised directly in Civitavecchia and capable of interacting with the corresponding NATO and Allied centres. It allows to train regiment, brigade and division commanders, and their respective staffs, in the exercise of the Command and Control function but also serves to conduct insights into certain aspects of operations and to evaluate alternative solutions for certain decision-making processes.

Live simulations rely on five Tactical Training Centers (CAT): Capo Teulada (in Sardinia), Torre Veneri (in Puglia), Monte Romano and Cesano (in Lazio) and Brunico (in South Tyrol). These simulations represent actions with real weapons, actions in which soldiers and vehicles are equipped with "duel simulators" and various sensors capable of defining the effects of the actions taken by the units facing each other.

The Virtual simulation is based on the commercial product Virtual Battlespace 3 (VBS 3), a system based on very powerful and flexible commercial HW, which allows personnel to be trained in an engaging way, personalizing the training of the individual/team through models (avatars).

THEaeronautics has set itself the objectives of its Modeling and Simulation organization as those of training the operators, but also those of assisting the problem solving and decision making processes, therefore the objectives A and B reported at the beginning of the article (source: Ref. 2).

The M&S structure is now under the dependencies of the "Aircraft Space Control Training Department" (RACSA), part of the Aerospace Control Brigade (BCA) and based at the Pratica di Mare airport. Above all, the simulators of equipment, not always located at the headquarters of the RACSA department, are part of the simulation capabilities of AMI, both sensors (TPS77 Radar) and aircraft (and here the range is very wide, from various types of EuroFighter simulators, to those of the Tornado, UAV, AMX, C130, etc.). But among RACSA's mission there is also that of setting up a "Modelling&Simulation Pole" of the AM in the Airspace Control sector, capable of simulating the main airspace control capabilities, integrating sensors and tactical links, and therefore dialogue with the simulation networks of the other armed forces.

La Marina it has the most diversified structure, probably as it is intended to operate on the three elements (sea, land, air). Traditionally, simulation assets have been devoted to training (hence, once again objective A of the reported at the beginning of the article). At least at the beginning of the history of the Taranto Aeronaval Training Center (MARICENTADD), it was above all training systems intended to simulate isolated subsystems (torpedo launcher, artillery piece, gas turbines, etc.) but it was immediately also present the "tactical" simulator (RAT) as regards the combat function (details in Ref. 2). At least at the beginning, the major limitation of this series of simulators was the lack of integration, so each worked individually. The situation changed when the navy equipped many units with the C2 SADOC system (Combat Operations Automatic Management System) and therefore the need arose to develop a special structure for software development and validation. Starting from this simulation infrastructure, each subsequent simulator was designed with the requirement of integration with the SADOC simulator (also via HLA architecture). This group of simulations is the backbone of the Navy Programming Center (MARICENPROG), reporting directly to the C4S Command and in close coordination with MARICENTADD (see Ref. 3). The interesting element for the purposes of this story is that the MARICENPROG is, by its nature, also and above all responsible for the objectives C and D reported at the beginning of the article: the development of new requirements and the validation of the SW released by the suppliers of the MMI.

The international scenario: USA and NATO

To understand what happened and is happening internationally, we could start from the 90s, and exactly from what happened in the USA.

The American Department of Defence, in the early 90s, became aware of the potential and the effects on the world of defense of Modeling & Simulation technologies. Thanks to the increase in computing power and the results of the SIMNET project (the SIMulator NETworking project, started in 1984, had the ambition to connect just under a hundred simulators on 4 sites, and ended up with about 250 simulators on 9 sites , see Ref. 5), US DOD entrusted responsibility for all Modeling & Simulation activities to USD for Acquisition and Technology to develop a Vision on M&S, a vision summarized in the 1995 Modeling And Simulation (M&S) Master Plan Ref. 6. In this document we started to define what were the lines of activity to monitor and organize: establish Policies and Guidelines, understand what the fundamental requirements were, develop the technology, build and release the simulation capabilities (see Figure 1)

Figure 1: The 1995 US view on M&S, taken from Ref. 6.

Today the models in the USA have grown exponentially (well over 3000, according to Ref. 5) and are practically impossible to summarize.

More interesting, also because it concerns us directly, to understand what happens within NATO.

The organization that, within NATO, is responsible for planning the M&S activities among the members is the NATO Modeling and Simulation Group (NMSG) which reports to the Scientific and Technical Committee (STO). All NATO stakeholders and experts interested in Modeling and Simulation (M&S) come together under the coordination of the NMSG.

The group's mission is to promote cooperation between NATO and partner nations in order to maximize the effective use of M&S technologies. In fact, its activities include standardization, training of operators in the M&S domain and scientific and technological research in this area. The group is nominated by the Conference of National Armaments Directors (CNAD). Among the results produced, it is worth noting the NATO M&S Master Plan (NMSMP). The plan responds to the objectives in Figure 2, therefore it covers the activities of standardisation, exploration of new technologies and planning of the offer of common services which the member nations can make use of.

Figure 2 : NATO NMSMP plan, main objectives

Also in the M&S branch, on a more operational side, the NATO Supreme Allied Commander Transformation of Norfolk established the Modeling & Simulation Center (NATO M&S COE) in Rome (based at the Cecchignola barracks) qualifying it as a NATO Center of Excellence.

The NATO M&S COE is dedicated to promoting M&S in support of operational requirements definition, training and interoperability. The center has a primary role in promoting the use of M&S methodologies, and for this reason it involves NATO structures, governments, universities, entities that operate simulations. It intends to operate in numerous fields: Training and Education, Knowledge Management, Best Practices and analysis of M&S experiences, experimentation and development of new concepts, development of new standard doctrines and interoperability (see Ref. 7). It is easy to find the MSCOE "Annual reviews" available online, documents that detail the activities carried out. For example, taking a look at the 2017 Annual Review, one discovers how the MSCOE has supported the concept of M&S as a service, how it has contributed to the MSG-145 topic (one of the topics to be explored according to the NMSG and therefore contained in the NATO M&S Master Plan already mentioned) on a new simulation interoperability standard known as C2SIM, or how it contributed to the Coalition Warrior Interoperability eXercise (CWIX), an innovation event that brings all systems and network engineers together in one place (event of the which we will discuss in more detail later).

Among the NATO infrastructures destined for M&S we cannot fail to mention the CFBLNet (see Ref. 8). It is a network intended to support interoperability-related exercises and training whose formal Technical Agreement was signed in August 2002. There is no single nation that owns the CFBLNet, but each nation is responsible for its own network segment. The infrastructure is a secure and globally federated network intended to verify any interoperability issues and to test the capabilities of the Command, Control, Communications, Intelligence, Surveillance and Recognition systems. The CFBLNet network currently has 268 cross-certified secure sites, located in 14 NATO nations. The Italian side is the Command and Control Systems Management and Innovation Department (Re.GISCC) of AMI, located in Pratica di Mare, which ensures interconnections with the NATO network.

Figure 3: The connectivity of CFBLNet (from Ref. 4)

Having seen so far the NATO structures that deal with the standardization and guidance of M&S, let us briefly mention some of the structures that can be considered users of M&S technologies and infrastructures.

Surely one of the most important is the NATO Communications and Information Agency (NCIA). Founded in 2012 as a merger of pre-existing entities1, inherits all activities2 in the C4ISR field, in ballistic missile defense (BMD), in interoperability and in the definition of systems architectures and their testing. NCIA is a natural user of M&S technologies and infrastructure for both NCIA test interoperability activities and multilayer ballistic defense expertise. To test interoperability solutions, the most effective and valid solution is in fact to simulate the systems with which to interoperate (situation where in addition to a real system, usually the one under test, you have the simulated "rest of the world"). And, as appears even more evident, in order to carry out exercises and/or validations of anti-ballistic systems, it is difficult to take the path of making use of real threats with which to make the systems interact.

One of the infrastructures that is directly managed by the NCIA is the Integration Test Bed (ITB). It is an essential infrastructure for the integration, verification and validation of all ballistic missile defense and airspace control systems. It is capable of simulating systems interconnected to the system under test and interfacing with real systems, thus being able to simulate and stimulate various national assets such as BMD weapon systems, sensors and BMC3I systems. The ITB infrastructure, operational since 2007 and originally designed for the ALTBMD program, has proven to be essential both for NCIA's own NATO-level activities but also as a support to national simulation and/or development activities. It is no coincidence that over time the Italian armed forces have also equipped themselves with a similar infrastructure, the national ITB, a joint simulation laboratory that can be connected to the NATO ITB but above all capable of verifying the integration of connected national systems and platforms network and simulate operating models. If the national ITB structure originated by virtue of the Italian participation in the ALTBMD program (Ref. 14) and is now used for various joint activities and as support to the Forza–NEC (Network Enabled Capabilities) program activities, see Ref. 15 )

For the above reasons, NCIA is among the major contributors to several joint exercises within NATO.

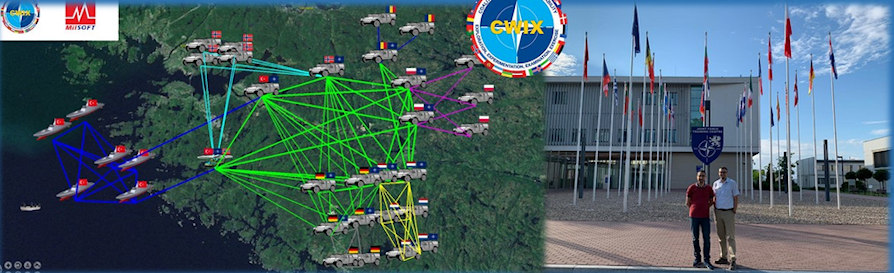

One event that should certainly be mentioned is the Coalition Warrior Interoperability eXercise (CWIX, see Ref. 9), the largest interoperability event in NATO, which is held annually and provides a unique opportunity for system engineers and interoperability experts to experiment and research innovative solutions. It is no coincidence that both the NCIA and the MSCOE play a leading role at the latest CWIW.

Figure 4: Representation of an exercise operated during CWIX 2019 with the involvement of a company from a NATO member country

Typically held at the Joint Force Training Center in Bydgoszcz, Poland, CWIX showcases systems ranging from deployed to experimental C3 systems. CWIX is an event for federated and interoperable systems, where most of the systems under test are operated by Joint Forces Training Center (JFTC) with many nations operating via the aforementioned CFBL network. For example: More than 2019 tests were performed in CWIX 8000 with more than 300 different systems involved (Ref 11). The Italian participation in this event has always been significant (see Ref. 12 and Ref. 13).

Another event impossible to have without the help of M&S technologies and skills is the Joint Project Optic Windmill (JPOW), under the responsibility of the Joint Air Power Competence Center (JPAACC). It is an exercise that is held annually in the Dutch air base of De Peel, and tends to evaluate the ability of NATO member countries to carry out one of the most difficult missions, that of Integrated Air and Missile Defense, IAMD ). It is an exercise involving various defense systems3 which extends to the development of new concepts and the testing of systems that are not yet operational.

Figure 5: The context of a JPOW exercise

The JPOW also takes place thanks to the CFBLNet network and the simulation potential that allows sharing a common Air Picture with the simulation of threats and the simultaneous presence of real air tracks.

Read the first part "What are simulation models: origin and evolution"

Read the second part "What are simulation models: the defense context"

1 NCIA is the result of the merger of: a) NATO Communication and Information Systems Services Agency (NCSA); b) of NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency (NC3A); c) of the NATO Air Command and Control System Management Agency (NACMA), d) of the NATO Headquarters Information and Communication Technology Service (ICTM); of e) Program Office for NATO's Active Layered Theater Ballistic Missile Defense (ALTBMD).

2 From the NCIA institutional site Ref. 10 we read: NCI Agency delivers advanced Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) technology and communications capabilities in support of Alliance decision-makers and missions, including addressing new threats and challenges such as cyber and missile defence. This includes the acquisition of technology, experimentation, the promotion of interoperability, systems and architecture design and engineering, as well as testing and technical support. It also provides communication and information systems (CIS) services in support of Alliance missions.

In addition, the Agency conducts the central planning, system engineering, implementation and configuration management for the NATO Air Command and Control System (ACCS) Programme. NCI Agency also provides co-operative sharing and exchange of information between and among NATO and other Allied bodies using interoperable national and NATO support systems.

3 Systems involved in JPOW 2017: PATRIOT PAC 3, Terminal High Altitude Air Defense System (THAAD), AN/TPY2, C2BMC, Air Defense Command Frigate (ADCF), F-124, F-100, SAMOC, AEGIS Afloat and AEGIS Ashore, the Maritime Theater Missile Defense Forum, Deployable Control & Reporting Centers (D-CRC) and ground based AMRAAM.

References

Ref.1 - Cesiva: https://www.esercito.difesa.it/organizzazione/capo-di-sme/COMFOTER-COE/C...

Ref.2 - Modeling & Simulation in military training. The experiences of the main Armed Forces in the world and a possible model for Defense - Group thesis 2nd section - 5th WG 17th Joint Staff Higher Course, Higher Defense Studies Center

Ref.3 - Fifty years of MARICENPROG, DifesaOnLine, https://www.difesaonline.it/news-forze-armate/mare/cinquanta-anni-di-mar...

Ref.4 - Combined Federated Battle Laboratories Network (CFBLNet) Guide, Ver. 2.0, Oct. 2019

Ref.5 - A HISTORY OF UNITED STATES MILITARY SIMULATION, Raymond R. Hill JO Miller, Department of Operational Sciences, Air Force Institute of Technology

Ref.6 - Modeling And Simulation (M&S) Master Plan, DoD 5000.59-P, October 1995, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology

Ref.7 - Site of the NATO Center of Excellence on MSCOE Simulation: NATO https://www.mscoe.org/mission-and-vision/

Ref.8 - CFBL Net Video Overview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ihUF409T900&t=0s

Ref.9 - CWIX Home Page: https://www.act.nato.int/federated-interoperability

Ref.10 - NCIA institutional website: https://www.ncia.nato.int/

Ref.11 - NCIA Involvement in CWIX 2019: https://www.ncia.nato.int/about-us/newsroom/nci-agency-plays-key-role-in...

Ref.12 - CWIX 2021: https://www.difesaonline.it/news-forze-armate/interforze/conclusa-leserc...

Ref.13 - CWIX 2016: https://www.difesaonline.it/news-forze-armate/interforze/polonia-conclus...

Ref.14 - National Association of Technical Officers of the Italian Army (ANUTEI), NATO ALTBMD Program - Italian perspective and commitment, 20 November 2008 - http://www.anutei.it/attivita/2008/semsabaudia/atti/Documenti/7_8_PERA%2...

Ref.15 - New frontiers of the Army: training simulators and the development of digitization (link)

Images: Italian Army / web / US DoD