I was born in 1970: a quarter of a century after the end of the Second World War. I have no memory of traces of the conflict during my childhood.

As a boy I listened to the stories of my grandfather, of his terrible experience (two years) as a soldier in Russia, of the retreat... but they seemed like truly remote memories and concerned a man and his generation.

For decades I then believed that being Italian was equivalent to being French, English or even American. At the same time I have always asked myself the reason for the ineptitude of our politics; the foreign one in particular.

I just read a book on the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947, the outcome of our "unconditional surrender" of 1943: a substantial moral and material condemnation of Italy with territorial renunciations, drastic downsizing of the armed forces and political, economic and financial allowances signed in white.

We boldly celebrate the "War of Liberation" every year: an officially phase of "cobelligerence", whose main price was - as usual - paid by the civilian population. However, a real "bloodbath" cannot be emphasized enough, the very high toll suffered by the Allies on Italian soil in the relevant two-year period (between 300.000 and 400.000 dead, missing and wounded).

And the surrender of 1943? Don't worry...

To bring to light an event almost buried in the Italian collective unconscious, we interviewed a diplomat and essayist who has addressed that historical period in numerous works: ambassador Domenico Vecchioni*.

Has having signed an "unconditional surrender" actually been "removed" from our collective consciousness?

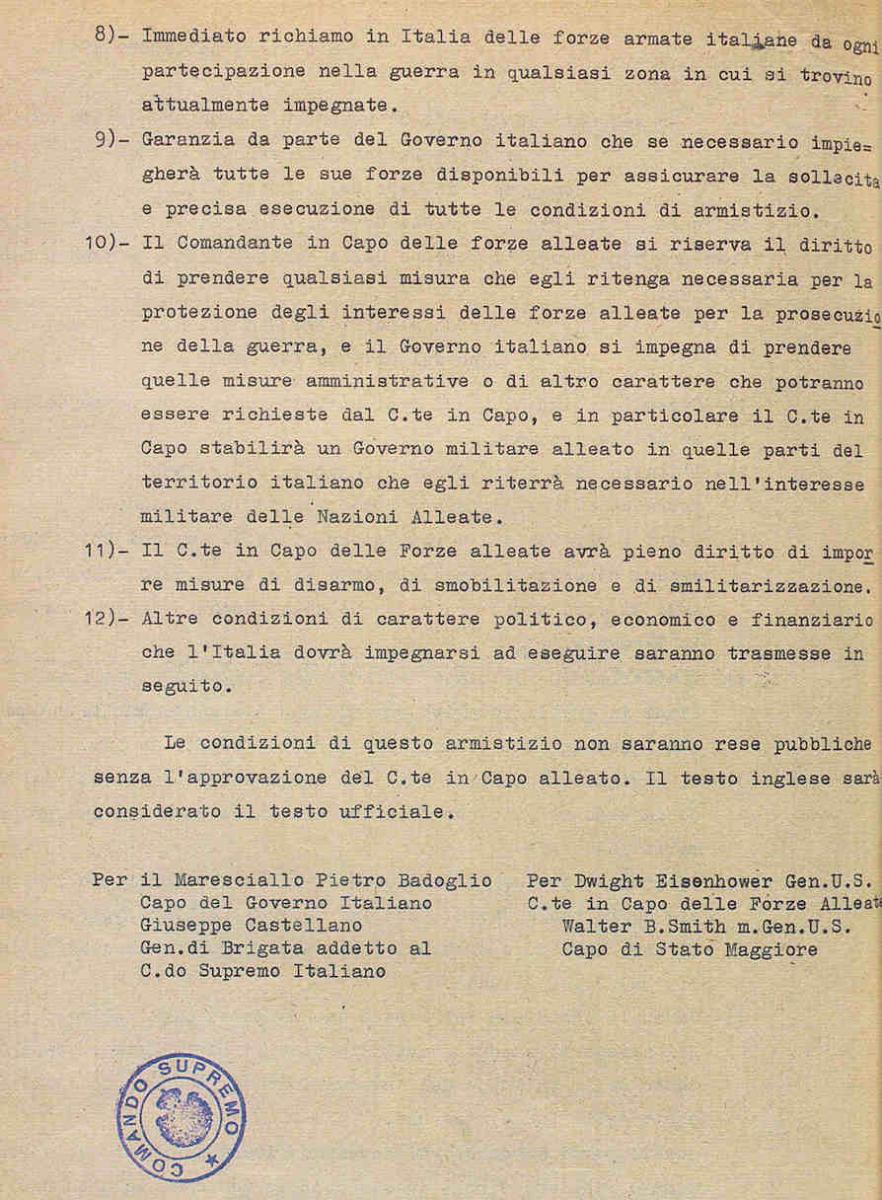

I don't think it was removed because basically... there was never full awareness of the "unconditional surrender", a principle established by the allies in the Casablanca conference of January 1943 (photo). With the enemy powers there would have been only one possibility of agreement: "unconditional surrender"!

I don't think it was removed because basically... there was never full awareness of the "unconditional surrender", a principle established by the allies in the Casablanca conference of January 1943 (photo). With the enemy powers there would have been only one possibility of agreement: "unconditional surrender"!

September 8, in fact, has always been presented to us as "the armistice". But the armistice is concluded between warring parties when they choose to take a "pause", a suspension of war activities to determine what to do next, whether to continue the war or negotiate peace. Now it seems to me that all the conditions foreseen by the allies were simply imposed on Italy. Not only. The surrender was signed in two stages.

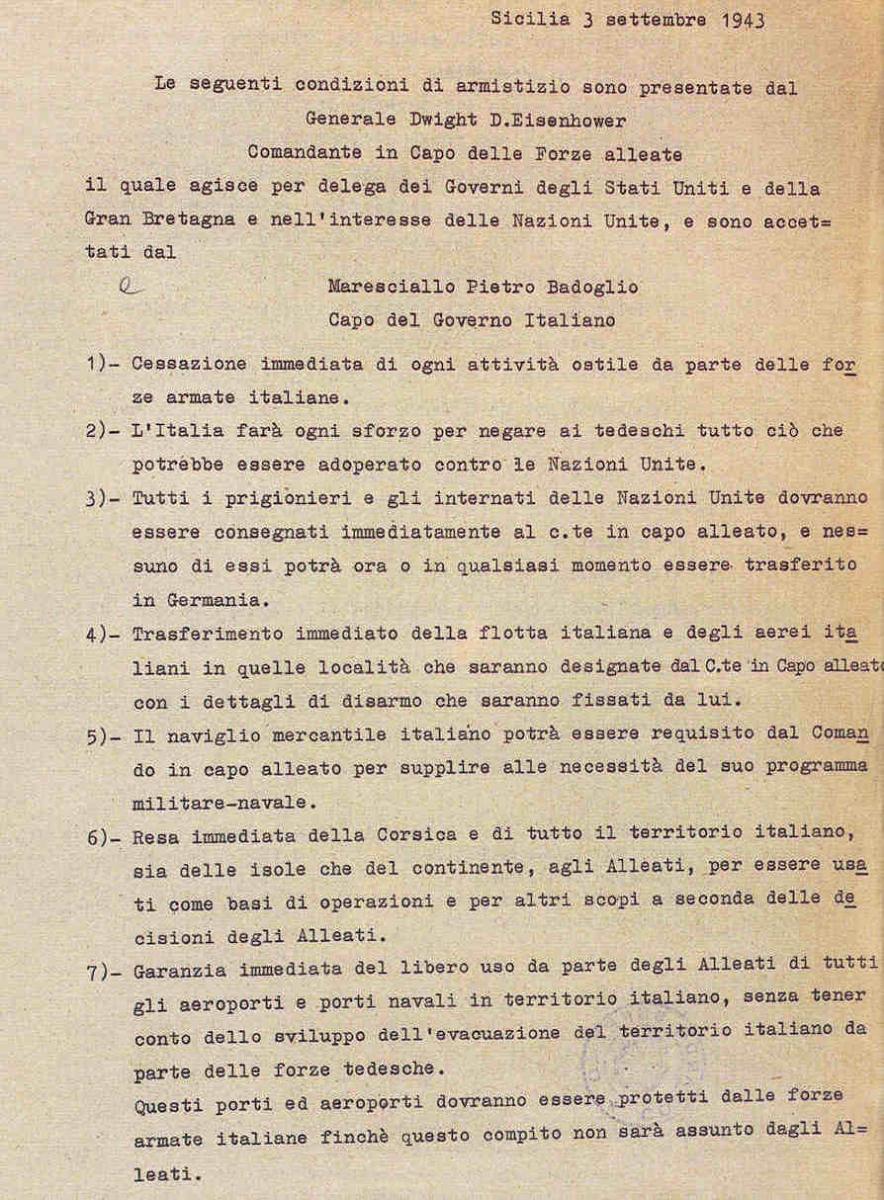

On 3 September, in Cassibile, the short armistice was defined (opening photo), which contained the essential clauses for the cessation of hostilities and was issued only on 8 September.

On 29 September the long armistice was then signed on board the battleship Nelson (in the harbor of Malta) which contained more detailed clauses of a political, economic and financial nature. which, among other things, they did to lose all autonomy to Italy in the international field.

Our ambassador in Madrid, Giacomo Paulucci de' Calboli, bitterly verified this when he received the order from Badoglio to deliver to his German colleague the declaration of war on Germany, which was passing from a "German ally" to the status of enemy number one. The German ambassador, however, opposed him with a decisive "fin de non-recevoir"! That document was for him inadmissible because Italy, with the armistice clauses, had lost all decision-making capacity in foreign policy.

September 8 should be remembered not as the date of the armistice, but rather as the day of surrender. Historically it would be more correct. Whether it was good or bad for the country to surrender is a question that concerns another and broader historical debate.

I agree and I certainly don't blame the Allies: we lost. There much celebrated "Liberation", in fact, had little if any (!) impact on the 1947 Peace Treaty. Why divert attention, for almost 80 years, from a fundamental document?!

What is your opinion of Badoglio?

A real leopard! He served several regimes, obeyed multiple leaders, always trying to combine national interests with his personal benefits.

A real leopard! He served several regimes, obeyed multiple leaders, always trying to combine national interests with his personal benefits.

Badoglio betrayed Mussolini for political and military reasons. That is, to spare Italians further mourning and devastation. But he did it badly, without a precise vision, in the absence of physical and moral courage and the predisposition to assume one's responsibilities.

He acted in such a disorderly manner that he earned the contempt of the Germans, without acquiring the esteem of the allies, who never held him in high regard. His greatest betrayal, however, was not that of having arrested the man who had brought him to triumph after the conquest of Ethiopia, or of not having done enough to avoid the fall of the king who had revived him from hibernation as an anti-war -Mussolini. His greatest betrayal was that of the Italian people, left to fend for itself for 45 days; was that of having fled Rome without even attempting to defend it, abandoning the Romans to their fate; he was the one to have accepted a surrender "unconditional" without having tried to attenuate the very harsh clauses which canceled all Italian sovereignty.

For him the allies created a neologism that says a lot about the prestige enjoyed by the Marshal of Italy among the allies: "to badogliate". That is, betraying in a messy, confused, clumsy, cunning way... like Badoglio, exactly.

In light of what we are discussing, aren't the limits of politics (foreign in particular) of the last 80 years finally understandable? We remember that the elimination of Italian colonial possessions was also imposed...

Of course, the seeds of the treatment that would be reserved for Italy after the war had their first cultivation in very hard armistice clauses. The ambiguous formula of "cobelligerence" did not earn us much credit with the allies. It turned out to be only an instrument of Allied (especially English) political propaganda.

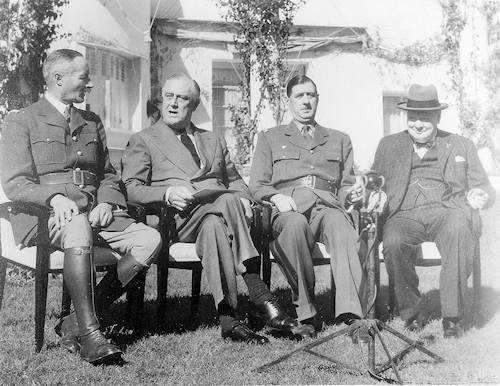

Suffice it to say that Italy, always conditioned by heavy diplomatic constraints imposed by the super powers, was admitted to the UN only in 1955 (Photo), ten years after its foundation.

In your career as a diplomat, was the signing of the 1943 surrender always, on the contrary, always very present? Was she ever "remembered" by anyone?

No, I have to say no. I have never had the opportunity to talk with colleagues about such burning topics in national history. And on the other hand, as we know, the golden rule of diplomats when they participate in social events is to avoid discussing two topics as much as possible: politics and religion. On these paths the discussion can easily slip, take unpredictable directions and get out of control...

To overcome a deep trauma one must - sooner or later - face it. Could rediscovering and finally accepting defeat and above all unconditional surrender help Italy's "liberation" from incomplete rhetoric?

80 years after the events, the time that has passed should allow us to look at our history with greater detachment and realism, avoiding approaches conditioned by politics, if not by ideology. A historical approach to get us as close as possible to the truth. At least for certain facts and events, the interpretation of which may always vary, but do not cast doubt on the event itself.

I mean a defeat is a defeat. The causes, consequences, etc. can always be discussed. But we must start from the objective recognition of defeat, otherwise the discussion becomes confused. As a surrender is a surrender, not an "armistice".

That of September 8th was therefore one unconditional surrender. Let's start from this assumption to better understand what happened next...

Photo: web

* After graduating in Political Sciences, he won the competition to enter the diplomatic career. He served in Le Havre (consulate), Buenos Aires (embassy), Brussels (NATO) and Strasbourg (Council of Europe). At the Farnesina he held the positions of head of secretariat of the general directorate of cultural relations, head of secretariat of the general directorate of personnel, head of the "Research, Studies and Programming" office and inspector of Italian embassies and consulates abroad. He was then consul general of Italy in Nice and Madrid. Permanent deputy representative at the Council of Europe, from 2005 to 2009 he held the position of Italian ambassador to Cuba. He received various honours, including that of "Chevalier des Palmes académiques" and Commander of Merit of the Italian Republic. Historian and essayist, he has collaborated with magazines on international politics (Rivista di studi politica internazione), on history (Storia illustrata, Cronos, Rivista Marittima, scienza la storia, Civiltà Romana), on intelligence (Gnosis, Intelligence and Storia top secret). He regularly collaborates with BBC History / Italy and is the author of around thirty historical-political essays. He was also interested in the biographies of famous people, with particular reference to the protagonists of global espionage. For Greco e Greco he has, among other things, published: Richard Sorge, Kim Philby, Ana Belén Montes, Garbo, History of secret agents from espionage to intelligence, XX extraordinary destinies of the twentieth century, Cicero, the most intriguing spy-story of the 2nd World War. At Edizioni del Capricorno he published "The ten operations that changed the Second World War" (2018) and "The ten female spies who made history" (2019). He is registered in the national register of intelligence analysts (ANAI ). Editorial director of the series, "Ingrandimenti" and "Affari Esteri", at the "Greco e Greco" publishers in Milan. His complete bibliography (books, ebooks, articles) can be consulted on his website: www.domenicovecchioni.it

* After graduating in Political Sciences, he won the competition to enter the diplomatic career. He served in Le Havre (consulate), Buenos Aires (embassy), Brussels (NATO) and Strasbourg (Council of Europe). At the Farnesina he held the positions of head of secretariat of the general directorate of cultural relations, head of secretariat of the general directorate of personnel, head of the "Research, Studies and Programming" office and inspector of Italian embassies and consulates abroad. He was then consul general of Italy in Nice and Madrid. Permanent deputy representative at the Council of Europe, from 2005 to 2009 he held the position of Italian ambassador to Cuba. He received various honours, including that of "Chevalier des Palmes académiques" and Commander of Merit of the Italian Republic. Historian and essayist, he has collaborated with magazines on international politics (Rivista di studi politica internazione), on history (Storia illustrata, Cronos, Rivista Marittima, scienza la storia, Civiltà Romana), on intelligence (Gnosis, Intelligence and Storia top secret). He regularly collaborates with BBC History / Italy and is the author of around thirty historical-political essays. He was also interested in the biographies of famous people, with particular reference to the protagonists of global espionage. For Greco e Greco he has, among other things, published: Richard Sorge, Kim Philby, Ana Belén Montes, Garbo, History of secret agents from espionage to intelligence, XX extraordinary destinies of the twentieth century, Cicero, the most intriguing spy-story of the 2nd World War. At Edizioni del Capricorno he published "The ten operations that changed the Second World War" (2018) and "The ten female spies who made history" (2019). He is registered in the national register of intelligence analysts (ANAI ). Editorial director of the series, "Ingrandimenti" and "Affari Esteri", at the "Greco e Greco" publishers in Milan. His complete bibliography (books, ebooks, articles) can be consulted on his website: www.domenicovecchioni.it