The contrast between Shiites and Sunnis, which has characterized all Arab history practically from the origins of Islam, but which had not given rise to militarily and politically relevant conflicts between Arab countries, suddenly exploded in conjunction with the Iranian revolution of 1979, which brought to the fore a new actor characterized by a strong hegemonic vocation, immediately perceived as a serious threat to the power system and the regional weight of the Gulf monarchies, especially those with large Shiite minorities, such as Bahrain and Kuwait. A fracture, therefore, which not only led to separation of Iran from the Western world (which had initially and erroneously considered it a "lesser evil" compared to a possible communist drift in the face of a monarchical regime in very serious crisis) but also, in a virulent form, from the Sunni Arab world.

However, at the origin of the current tensions between the two components of the Arab world there was not so much the religious factor as the political one. search for regional supremacy. The clash between powers that fought, and still contend, for supremacy in the region is not, therefore, characterized by a war of religion but by exploitation of religion for political ends.

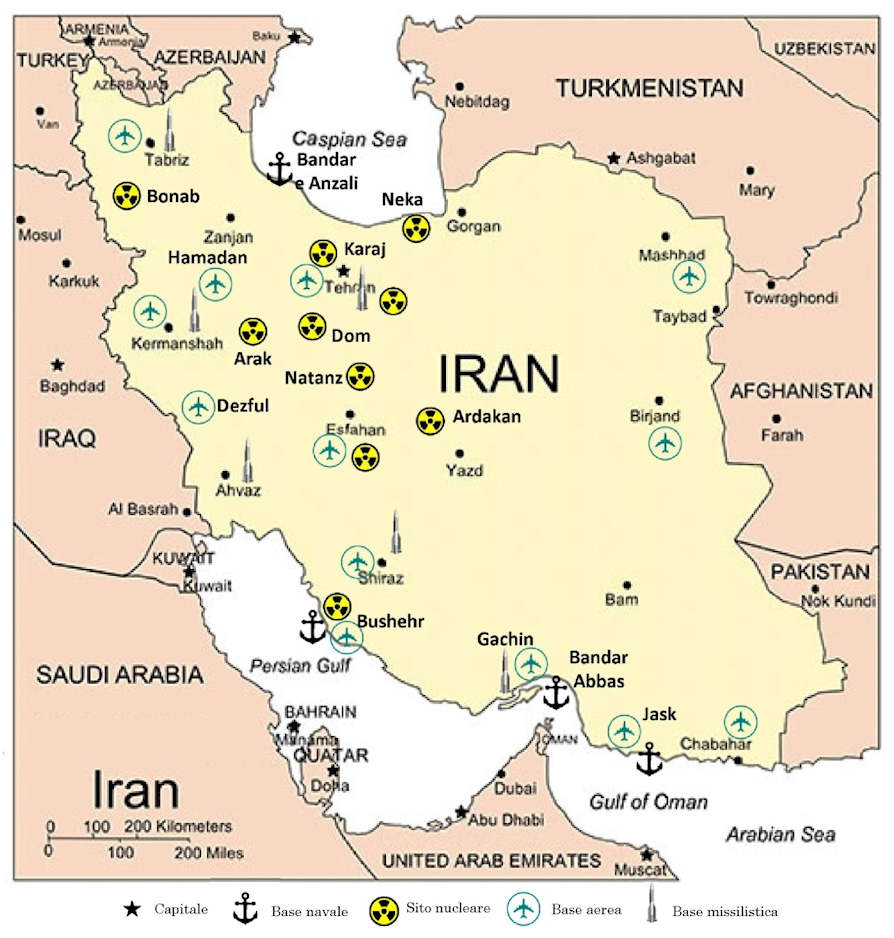

The expansion of Iranian influence in the Middle East has developed mainly through Arab-Shiite parties and armed groups of reference in Iraq and Lebanon. However, although not secondary, the terrestrial aspect of the strategy of expanding its influence is today overtaken by the maritime activism of the Islamic Republic of Iran which, in this crucial space under the energy and geopolitical profile, directly impacts on the traffic of energy resources directed to the rest of the world. An action that is, as we will see later, facilitated by the presence of an important obligatory passage for ships, the Strait of Hormuz, the gateway to and from the Persian Gulf.

It is a passage of just under 100 nautical miles in length and a width varying between 22 and 35 miles. Furthermore, since Omani coastal waters are shallow, navigation normally takes place on routes closer to the Iranian coasts and this makes Tehran's destructuring action even easier.

It is a passage of just under 100 nautical miles in length and a width varying between 22 and 35 miles. Furthermore, since Omani coastal waters are shallow, navigation normally takes place on routes closer to the Iranian coasts and this makes Tehran's destructuring action even easier.

It is therefore worthwhile to analyze the Iranian maritime strategy, in order to try to understand what its possible implications could be on the geopolitical equilibrium of the area in the medium to long term.

Previous

The Iranian Naval Forces were born in 19321 and constitute both a reason for national pride and an instrument for the affirmation of regional ambitions by the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. The elitist nature of the Iranian Navy is represented within it by the presence of numerous family members of the Shah, as officers. A preference that is also reflected in the allocation of economic resources, in particular during the last decade of the reign, which lead to the launch of important naval development programs.

The 1979 revolution, in addition to the evident and well-known socio-political aspects, will also bring substantial changes to the Iranian military instrument, in particular to the imperial navy. First, all naval development programs are immediately suspended. As for Navy personnel, most officers are regarded as potential counter-revolutionaries by the clerical regime and, as a result, some are imprisoned or murdered, others are fired or forced to resign or exile. A political-ideological clean-up that causes both a significant overall weakening of the Iranian maritime military instrument and an outright cessation of military cooperation with the West. The Naval Forces are later renamed as the Navy of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

To this is added the fact that, in the aftermath of the seizure of power, Ayatollah Khomeini wanted, for various reasons, a duality of the national naval forces by dividing them between the conventional Navy, which sees its area of competence in the waters beyond the Strait of Hormuz, e Pasdaran (in Persian it means "those who watch", also known as "the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution"), which have the main operational theater in the waters of the Gulf and, in particular, of Hormuz (this explains their continuing tensions with the 150th fleet USA, based in Bahrain). A duality that is reflected in art. XNUMX of the Iranian Constitution, where it states that “… The body of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, organized after the triumph of the Revolution, must be maintained so that it can operate according to its role and objectives. Its tasks and areas of responsibility, in relation to the tasks and areas of responsibility of the other Armed Forces, will be determined by law, with an emphasis on fraternal cooperation and harmony between them. ... "2.

The Iranian maritime strategy

The Iranian maritime strategy

Taking into account the balance of power of the moment, the maritime strategy conceived by the ayatollahs envisages an asymmetrical response, implemented by employing many small fast vessels to limit access to the Gulf by hammering and trying to saturate the opposing defenses. These small units can be equipped with anti-ship missiles and are capable of both naval mine-laying operations and attacking "in swarms", using rockets and small arms.

The goal is to create conditions that make access to the Gulf very complicated, not through the use of large and powerful ships but through the presence of many small and fast platforms (we are talking about fifty missile units of 200 tons and hundreds of smaller platforms armed with machine guns and rockets). A strategy hypothesized in 1874 by Théophile Aube, the French admiral considered the founder of Jeune Ecole3.

An operational choice, that of having overall modest naval capabilities, which indicates post-1979 Iran "... does not intend to fight for supremacy in the Gulf waters, but to prevent that of the USA, through the use of low-cost tools, in order to limit the opponent's ability to maneuver ..."4. A strategy designed both to counter perceived US hegemonic ambitions and to oppose other regional rivals, such as Saudi Arabia.

Nonetheless, Iran is careful not to get caught up in wider regional conflicts, which could extend its international isolation, and not to cross the threshold of a fatal provocation, well aware that the US has over 30.000 troops in the area. , not to mention aircraft carriers, missiles, bombers and amphibious assault groups.

Nonetheless, Iran is careful not to get caught up in wider regional conflicts, which could extend its international isolation, and not to cross the threshold of a fatal provocation, well aware that the US has over 30.000 troops in the area. , not to mention aircraft carriers, missiles, bombers and amphibious assault groups.

On 1 September, for example, the Iranian frigate jamaran (photo) recovered two US drones and only the immediate intervention of two US units, which were nearby, convinced the crew to return the material.

As far as personnel is concerned, the fact that the conventional Navy has about 18.000 men (data from 2021) is indicative of a certain political choice, while the naval component of the Pasdaran includes more than 20.0005.

As stated by Clément Therme, researcher ofInternational Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) in London, the main weakness of the Iranian maritime instrument is its infrastructure, most of which is quite dated. This poses obvious problems for the maintenance of ships and causes a lack of flexibility of the platforms used by naval forces.

Even in terms of training / technology, Iranian ships and crews do not shine, causing embarrassment in Tehran.

As reported by the agencies, on 10 May 2020, during a "hot" exercise, always on jamaran launched a "Noor" missile (long-range anti-ship cruise missile manufactured by Iran) which hooked, hit and sank the tender Konarak (next photo) instead of the towed target, causing 19 deaths and 15 injuries. And this was neither the first nor the most serious mistake made by the ships of the gods Pasdaran.

Another aspect of the Iranian maritime strategy is that relating to the attempt to break the political and military isolation following the revolution. In this context, Tehran has launched a series of (military) cooperation initiatives mainly with Moscow and Beijing. The global collaboration with China signed in March 2021, in particular, is aimed at encouraging the conduct of joint military and naval exercises. It is not a new thing, but the formalization of what has been done by Iran and China in the last ten years, having carried out some naval exercises together, such as in September 2014, June 2017, December 2019 and January 2022. The latest two also saw the participation of Russia (read article "Hong Kong, Beijing and the South China Sea")

Given that China has global maritime ambitions and is the largest oil importer from the area, It is very likely that Beijing will be able in the short / medium term to establish an important naval support point on the Iranian coast of the Gulf, in particular by leveraging the two countries' intention to increase the frequency of joint naval exercises. Beijing would thus have permanent access to a strategic space through which 30% of the maritime traffic of hydrocarbons passes.

In fact, it seems that informal negotiations have already begun to obtain access for 25 years to the Iranian island of Kish. News that would have been denied by the Iranian official bodies but that in Tehran continues to bounce between the walls of the rooms where it is decided, showing if only the interest of some in putting on the table the hypothesis of such an agreement. The fact is that the election of President Ibrahim Raisi in August 2021 made such an eventuality more concrete, since his strategy is based on a further rapprochement between Tehran and Beijing. All this is part of a geopolitical framework that is still quite tense.

The geopolitical framework

The Persian Gulf is an extremely important region not only for the world economy, but also for the general stability of that area of strategic interest known as the enlarged Mediterranean. It is an area plagued by political and military clashes (most recently the civil war in Yemen), often aggravated by ancient and lively ideological and religious disputes, and has been defined by many as a dangerous loose cannon in the contemporary world, potentially in able to condition the future of all those countries which, directly or indirectly, gravitate around it economically and / or politically.

As I have already mentioned, the instability of the area is generated both by the difficult coexistence of two giants such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, divided by the different religious orientation (Shiite the first and Sunni the second) and opponents for the dominance over the area, both because of the internal fragility of the various realms and emirates, still partly organized in a feudal manner, which are located overlooking the Gulf.

An explosive mixture that could seriously endanger the world economy. After about thirty years of war (Iran-Iraq, Gulf I and II) the equilibrium of the area has in fact profoundly changed and the entire region, very important for the world supply of oil and a hinge of relations with the Asia found itself in a new and, in many ways, still evolving context.

The delicacy of the area, which encloses a stretch of sea measuring about 160 miles in width by about 460 miles in length, is even more highlighted by its particular orographic conformation. Just think of what the obligatory passage through the Strait of Hormuz represents for merchant traffic.

Located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula, it is at the center of the most important sea routes in the world, especially for the oil trade. Just to understand its economic significance, Saudi Arabia alone in 2018 made about 6,5 million barrels of oil pass through the strait per day.

And it was precisely the Strait of Hormuz that found itself at the center of a serious international crisis in the recent past. It is there that, in the course of 2019, between attacks on oil tankers and killing of drones, the competition between Iran on the one hand and the United States and allies on the other has intensified. In this context, Riyadh no longer has diplomatic relations with Tehran since January 3, 2016. Abu Dhabi, on the other hand, seems to have recently been seeking a rapprochement with Tehran, so much so that, on August 13, 2021, it announced its intention to normalize its relations with that country. A surprise announcement that did not fail to arouse some perplexities also in Iran, given that on the following September 15, the UAE signed the Abrahamic Agreements, an act with which Israel - Tehran's bitter antagonist - became a full-fledged actor of the security architecture of the Gulf, as immediately underlined with the participation in naval exercises coordinated by US CENTCOM. In this context, Qatar, after settling the disagreements with the Saudis (January 5, 2021) generated by the serious crisis of June 5, 2017, proposed itself as a mediator between them and the ayatollahs, organizing meetings that so far have not yielded noteworthy results. (the latest on 21 April 2022).

While speaking with "licorice language", hoping for an agreement with the Saudis as the only way to calm the security situation in the area, Iran continues to act on the sea (see for example the case of jamaran).

In this context, the USA, despite President Trump's general policy of disengagement, wanted to maintain a strong naval military presence in the area, mainly thanks to the Saudi ally, with the "Operation Sentinel" together with units of Great Britain, Israel and South Korea. The Biden Administration, however, still appears to be applying a weak strategy with no clear horizon to the Middle East theater, as confirmed by the chaotic US flight from Kabul in 2021.

In this context, the USA, despite President Trump's general policy of disengagement, wanted to maintain a strong naval military presence in the area, mainly thanks to the Saudi ally, with the "Operation Sentinel" together with units of Great Britain, Israel and South Korea. The Biden Administration, however, still appears to be applying a weak strategy with no clear horizon to the Middle East theater, as confirmed by the chaotic US flight from Kabul in 2021.

Russia and particularly China, as mentioned, rely on Iran to ensure a capacity to participate in local issues. However, their influence will likely be tempered by complex local histories and many ethnic and sectarian rivalries.

All these national interests translate into a significant naval military presence in the area in the context of multinational operations, whose deterrence capacity against possible impediments to freedom of navigation is mainly manifested by escorting merchant ships, considered the most likely target. of hostile actions.

And Europe? Some European countries have decided to launch an operation called AGENOR as part of the "European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz" (EMASOH) initiative, which aims to ensure the European presence in this sensitive area with a military contingent with a predominantly maritime connotation, to avoid possible risks to merchant ships and crews in transit, an essential element for the economy of the old continent.

Italy participates with one of its units and, since July 2022, has assumed tactical command of the device. This commitment, together with the other international naval commitments in which Italy is fully present on the seas of the world, requires the ships to be fully operational. This requires political farsightedness and the application of a concrete strategic vision, which makes it possible to put aside vested interests and obsolete and restrictive visions of the past. Since it is our specific interest to remain in those waters, it is therefore essential to ensure every possible support to our units, allowing them to effectively "beat the wave" to protect prestige, legitimate interests and the national economy.

Conclusions

The orientation, or maritime vocation, of a country is judged by evaluating the importance assigned to the naval dimension in relation to the terrestrial one. In this context, it does not seem that Tehran assigns any particular importance to the maritime aspects with respect to those of internal security and stability. The Iranian maritime orientation, which was the main strategic direction during the last imperial period (1925-1979), has therefore become "only" one of the thousand aspects of the asymmetric military response of the Islamic Republic, to preserve its ideological identity without calling into question the survival of the revolutionary state. A system of power attentive above all to the internal situation where the current widespread protests against an overly suffocating method could, in the event of a concomitant serious military crisis, cause subsidence or lend themselves to subversive maneuvers of the regime, for the ayatollahs a precious heritage to be safeguarded before any other What.

Although the military budget has grown from USD 16,5 billion in 2020 to around 25 billion of 2021 and even if, despite the restrictions imposed by sanctions, it has maintained a certain industrial capacity for the production of missiles and drones, Iran does not appear capable, in the short and medium term, of sustaining a major naval confrontation or of preventing the transit of ships to and from the Persian Gulf through the application of the Anti Access / Area Denial (A2 / AD) strategy, a typically defensive strategy, generally applied by those who know that they do not have the strength to impose their will on the seas.

To this, however, it should be added that the very existence of the Strait of Hormuz also presents negative aspects for Tehran. If, in fact, on the one hand it is the only way to reach Iran by sea (in particular the large port of Bandar-Abbas), on the other it is also its only access to the major trade routes, since at the moment there are only announcements of plans to build a large commercial port near Jask. When it is eventually built, however, it would still be the only landing place along its nearly 640 km of coastline on the Arabian Sea. Consequently, even today the Iranian trade routes (especially those of oil) are still, so to speak, prisoners of the caudine forks of Hormuz.

While Tehran would like to aspire to be a global maritime player (in September 2021 a flotilla participated in some maneuvers on the Atlantic Ocean) and despite the supreme leader Alì Khamenei strives to regularly emphasize Tehran's autarkic maritime advances, such as the entry into service of the catamaran Soleimani (opening photo) last September, in the short and medium term its ambitions remain rhetorical and symbolic, given that Iranian military capabilities in the maritime sector are largely insufficient to impose its will on the seas and to significantly counteract, outside of Hormuz, the world merchant traffic.

However, despite having a modest overall naval capacity, Iran remains a leading actor in those waters, and is capable of constituting a non-negligible threat in the Strait of Hormuz area and influencing the flow of energy supplies to world trade routes.

1 Chelsi Mueller, The origins of the Arab-Iranian conflict: Nationalism and Sovereignty in the Gulf between the World Wars, Cambridge University Press, 2020

2 Full text in English on the website of the Iran Chamber Society, The Constitution of Islamic Republic of Iran

3 Renato Scarfi, Maritime aspects of the First World War, Ed.Ponte di Mezzo, 2018

4 Jean-Lup Samaan, Rivalités irano-saouidiennes: the dimension maritime, Moyen-Orient, 2018

5 International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), The Military Balance 2022

Photo: IRNA / Tasnim News Agency / web