From the first hours of the operation Al-Aqsa Flood, conducted by Hamas on Israeli territory, it was clear that Tel Aviv's reaction, once the Palestinian forces had been evacuated from the kibbutzim on the border with the Gaza Strip, would be oriented towards the definitive defeat of the enemy.

To defeat Hamas, transforming it into an actor no longer capable of harming Israel's security, the IDF has no other option than to enter the Gaza Strip in force and fight in cities such as Gaza City, Deir al-Balah, Khan Yunis and Rafah. The area of operation cannot, in fact, be limited exclusively to the northern area of the Strip, but must include the entire strip of Palestinian territory currently administered by Hamas.

“Surgical” military operations cannot be allowed if we want to give credence to the words of the Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, who announced the start of a long war. The situation, different from previous years, in which a rapid cross-border blitz is no longer enough and with the risk of regional extension of the conflict, has brought the clock back to 1948 and the Yom Kippur War of 1973, is addressed in new ways and requires also new political solutions. But it is clear that the events linked to the Al-Aqsa Flood and the next Israeli armed response also bring with them problems in certain "new" aspects, which are already emerging with the aerial and artillery bombings conducted by the IDF.

Part of the internal debate in Israel, while the armored vehicles with the Star of David are deployed on the border with the Gaza Strip, is precisely focused on the political consequences that the unprecedented attack by Hamas and the (now imminent) armed response of Israel will leave in the area.

Once they enter the Gaza Strip, the Israelis will find themselves faced with the Leninian dilemma of "what to do?" relating to the future of this portion of Palestine. Occupy it? If so, even in the face of open opposition from Washington? How long? Simply conduct surgery? This does not appear to be the case.

Meanwhile in the West Bank, tension is rising and the political questions posed by the settlers (who played a fundamental role in the defense of the kibbutzim and other settlements in the first hours of the Hamas attack, when the army seemed almost "paralysed" in the face of emergency and intelligence affected by the surprise effect), which carry forward a "radical" agenda, are at the center of important discussions. The settlers' political agenda, which already mattered a lot to the Tel Aviv government, will once again become a priority now that tension in the Palestinian territories is increasing.

Just as the risks of escalation with Hezbollah's Lebanon and Iran are around the corner. The exchanges of rockets and artillery fire between Israelis and Hezbollah militiamen, but also the bombings against Lebanese military infrastructure conducted by IDF helicopters, make clear how blurred the border is between latent conflict and open war on the northern border of the Jewish State , just as there is no doubt that Tehran intends to carry out one proxy war (which, due to a particular school case, he does not hide that he was the instigator) against Tel Aviv. Indeed, Iran has threatened clear retaliation if the IDF decides to cross the border into the Gaza Strip. This is the unmistakable signal, together with the presence of the US battle group led by the USS Gerald Ford in the eastern Mediterranean, and the US administration's announcement that it wants to send a second aircraft carrier to the area, the "regionalisation" of a war that will always have international implications and can never remain confined within that strip of territory called the "Holy Land" .

But the pace of diplomacy and saber-rattling will quicken or slow depending on the choices the Tel Aviv government makes to conduct its offensive on Gaza. It is a rare example of how even military tactics can influence "big politics".

The Gaza Strip, covering 140 square miles, is home to 2 million inhabitants, and is one of the most densely populated agglomerations in the world, at least as far as Gaza City is concerned, with nine thousand residents per square kilometre. Over the course of recent history, cities with a similar population density have been the scene of important battles and have been used by defenders to slow down the advance - already expected to be slowed down when planning an urban combat - of the enemy. Such cases are those of Baghdad in 2003, which involved the Taliban and the US army, Fallujah in 2004, between al-Qaeda militiamen and Anglo-Iraqi-Americans, Mosul, between Iraqi-Kurds and the Islamic State, and Marawi, between the Philippine army and the Islamic State, both in 2017, and the more recent examples of the battles of Kiev and Mariupol, in 2022, during the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war.

The environment of Gaza is not too different than that of the battles listed above. However, it should be noted that in Gaza the Israeli army may face new risks compared to the past, also due to the better organization and increased tactical-operational capabilities of Hamas. First of all, the presence of a vast network of underground tunnels could cause problems for the Israeli troops, with the Palestinian militiamen who will focus heavily on speed of movement, the creation of numerical superiority in specific points, during combat in progress, and close combat, through use of fortified strategic points identified mainly in buildings.

Furthermore, Hamas will use the civilian population as a "shield" to protect its positions from Israeli attacks. The freedom to open fire, determined by the cancellation of any rules of engagement by the leaders of the Tel Aviv armed forces for the soldiers who will be employed in Gaza, serves precisely to prevent the presence of civilian objectives on the ground from allowing Hamas to carry out undisturbed attacks against the IDF.

Another chapter is that of the attacks against Israeli tanks and armored vehicles in the streets of Gaza. The IDF will be forced to send armor forward, followed by infantry, to clear the ground. But the real risk is that the Palestinians could still inflict heavy losses on the Israeli "cavalry" via guided anti-tank missiles Malyutka (USSR), Konkurs (USSR), Bassoon (USSR) e Kornet (Russia) and anti-tank rocket launchers such as the RPG-7 (USSR) and the more modern RPG-29 (USSR). They are weapons already used by the Hamas militias and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad Movement in 2014, when Israeli troops entered Gaza for the last time, as part of the “Protective Edge” operation (8 July-26 August 2014), still present in the arsenals of the Palestinian forces.

The last element to take into consideration is that of rocket and drone warfare, which also John Spencer, of the Modern War Institute, wanted to highlight. Compared to past years, today Hamas has suicide drones, which were also used during the operation Al-Aqsa Flood, with ample space reserved for these actions by them official media of the terrorist group, with similar characteristics to Iranian HESA drones Shahed 136, also used by the Russian army in Ukraine under the name of Geran-2. The main characteristic of these drones is that they can be used for rapid actions, mounted on any mobile platform, not only military but also civil, such as their use in the field in Yemen by the militias Houthis showed. These are, therefore, systems extremely suitable for conducting both asymmetric warfare operations and clashes in a "closed environment" such as a city.

As regards the missile arsenal available to Hamas, in addition to the well-known short-range carriers Qassam-1, Qassam-2 e Qassam-3, in addition to Badr-3 created by the Palestinian Islamic Jihad Movement in 2019, the Palestinian terrorist-military groups in Gaza also have medium-range ones such as the Soviet BM-21 City and the Iranians Fajr-xnumx e Sejjil-55, or long-range ones Qassam-75, J-90, the Iranian Fajir-5, the R-160, the Syrian Kahibar-1 M302 and theAyyash-250. Many of the missiles in question were designed and built directly by Hamas experts, others, as we have seen, come from Iranian and Syrian arsenals or from Hezbollah stockpiles. The R-160 and theAyyash-250 According to experts at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, they are the missiles which, self-built directly in Gaza, show the most evident progress in Hamas' ballistic engineering. Both are long-range missiles, therefore unusable in an urban clash. Furthermore, for the first time, Hamas deployed its short-range anti-aircraft system on the field, Mubar-1.

The evolution of the conflict with Hamas and the principles of escalation underway both in the West Bank - where, among other things, the internal game within the Palestinian movement between the Palestinian Authority and the Palestinian Authority is being played - will depend on how the IDF chooses to face these threats on the field. Fatah and the radical group consisting of Hamas, Lions Den and Palestinian Islamic Jihad – both regionally with Iran. The choice to "liberalize" the fire of the Israeli military in the future operation on Gaza serves to strike the Hamas military structure as quickly and deeply as possible, avoiding prolonging the battle too much, to the point of forcing Israel to withdraw from its initial plan due to international pressure.

From this point of view, the easing of the blockade of Gaza, with the reopening of the Rafah crossing by Egypt under US pressure, does not benefit the Israeli strategy. But the hypothesis of a long conflict, as already explained by both Netanyahu and the leaders of the armed forces, is taken into open consideration by the State of Israel. What matters is not having to maintain a military force, even a large one (in 2014 the IDF employed three divisions for an operation limited in time and which had already announced itself as such), in Gaza, but to avoid, with rapid action that militarily dismantles Hamas and its allies in a short time, to broaden the boundaries of the war.

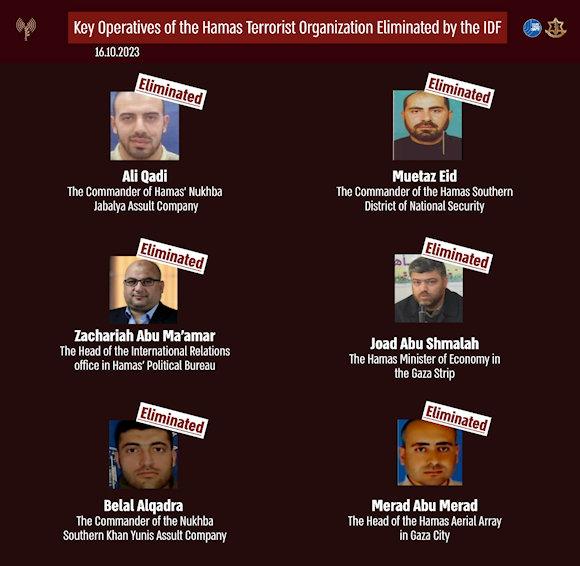

Image: IDF