The Mediterranean has always represented, for Italy, the main direction of political attention, even more today, that this area is home to important political and social ferments. It is, in fact, about "... a very complex system for geography, climate, culture and history. A sea large enough to accommodate different peoples with different interests, but still small enough for all events to end, in the end, to influence each other, add up and produce universal consequences ... "1. It therefore plays an irreplaceable role because it is home to a dense network of relationships and numerous strategic, economic and political interests, which go far beyond its geographical boundaries.

It should not be overlooked, however, that this area, of our direct interest, still represents one of the regions where conflict is strongest, due to situations that have their roots in too long unsolved political knots, on which, moreover, they have grafted terrorism facts. And this conflict grows when we talk about the exploitation of marine resources, which indifferently concern the extraction of hydrocarbons or fishing. We are, in fact, going through a period in which the search for resources makes many States eager to create an ever wider living space, often with actions that exploit a domineering and muscular reading of international standards. The main field on which these actions are manifested is the sea, in particular, now that technology can allow it to reach its most intimate and hidden resources. Always fundamental as a means of communication, the Mediterranean is an indispensable area for the transport of people, goods and raw materials, not only because it offers shorter and therefore cheaper routes, but also because these routes are relatively safer. Nonetheless, from the goods highway and food supplier, the "mare nostrum" has now become the scene of new, but old, reasons for international litigation.

Peaceful coexistence in a common area, in fact, presupposes common and balanced objectives of development and progress, without which nothing remains but antagonism, opposition and struggle. And this unfortunately seems to be the underlying motive of the current historical phase, characterized precisely by harsh contrasts and overbearing interpretations of international law.

In this dress the particular aggressive action of Turkey is highlighted, very active both from a military and political point of view, an activism that risks seriously disrupting (and is already doing so) the balance in the basin. How can we forget the decisive position taken by Ankara in the Syrian conflict, with the intervention of its troops across the border, an intervention that seems to have also allowed the release of numerous jihadists captured by the Kurds and kept in detention camps.

In the conflict in Libya, Turkey also resolutely took sides with Fayez al-Sarraj, employing troops and armaments on Libyan territory in support of the Government of National Agreement (GNA). The supply of armaments to GNA Libyans, despite the embargo ordered in 2011 by the United Nations, and the continuous provocative attitude recently manifested by Turkish warships risks causing dangerous frictions with the western military ships assigned to Operation Eunavfor Med "Irini "(In Greek it means" peace "), started last April by the European Union to enforce the provisions of the UN or with other maritime surveillance operations active in the Mediterranean. As, for example, the dangerous event recorded on June 10 during the NATO "Sea Guardian" maritime surveillance operation (which since November 2016 has replaced NATO "Active Endeavor") which, fortunately, is not been followed by more concrete actions. However, it was such as to suggest France to temporarily suspend its participation in the operation, in protest against the targeting of a Turkish military ship's radar against a French military unit (formally a NATO ally). A provocative and extremely aggressive action which caused the French temporary withdrawal from the operation starting from 1 July, but which could have triggered much more serious reactions and counter-reactions.

The issue was also examined during the last NATO defense ministerial, at the end of which the Secretary General communicated that the allied military authorities were instructed to investigate the matter.

Furthermore, al-Sarraj's support for Libya allowed Ankara to sign two bilateral agreements with Tripoli on 27 November 2019, one formalizing military cooperation and one concerning the delimitation of the borders of the respective maritime Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). In particular, the Turkish EEZ affects a large portion of the Greek territorial waters, confirming the aggressive Turkish expansion plan in the eastern Mediterranean. The EEZ agreement, in particular, has enormous economic implications, being the Levant Sea dense with gigantic gas fields (among others, Leviathan of 450 billion m3, Zohr of 850 billion m3, Noor estimated to triple Zohr) and the area claimed by Ankara would be an obligatory passage for any future gas pipelines going to Italy or Europe. An agreement that is considered illegal by both the European Union and the United States and which has not failed to raise many legal and economic doubts and doubts from many other coastal countries, triggering further reasons for friction.

Based on this agreement, Ankara has recently started oil and natural gas research operations off the coast of Kastellorizo, a Greek island just three kilometers from the Turkish coast, which is expected to last until August 2. The initiative, in which 17 military ships would be participating plus the hydrographic research ship Fasting Reis (photo) raised Athens' formal protests, followed by a strong Turkish response that Greek claims are contrary to international law, resulting in the dispatch of Greek military ships to the southern and southeastern Aegean . A tough dispute over more than ten years, that between the two NATO countries, on the rights to exploit the natural resources of the Aegean waters which now, as a result of the unilateral declaration of the Turkish EEZ, sees a further serious cause of friction added, between the growing embarrassment of Brussels trying to resolve the conflicts, serious to the point that, as some agencies report, the Hellenic Armed Forces have been mobilized and the alert status of many departments has been raised. Ankara, in fact, believes it has rights to the area south of Kastellorizo as part of its continental shelf, while Athens has always strongly denied it, denouncing a violation of its territorial waters. The notice of restriction of navigation in the area (Navtex) launched by Turkey for research, therefore, is seen as a serious threat to Greek national sovereignty over that stretch of sea, but not only. An arm wrestling which is potentially explosive and which can seriously challenge two countries still formally allied.

Based on this agreement, Ankara has recently started oil and natural gas research operations off the coast of Kastellorizo, a Greek island just three kilometers from the Turkish coast, which is expected to last until August 2. The initiative, in which 17 military ships would be participating plus the hydrographic research ship Fasting Reis (photo) raised Athens' formal protests, followed by a strong Turkish response that Greek claims are contrary to international law, resulting in the dispatch of Greek military ships to the southern and southeastern Aegean . A tough dispute over more than ten years, that between the two NATO countries, on the rights to exploit the natural resources of the Aegean waters which now, as a result of the unilateral declaration of the Turkish EEZ, sees a further serious cause of friction added, between the growing embarrassment of Brussels trying to resolve the conflicts, serious to the point that, as some agencies report, the Hellenic Armed Forces have been mobilized and the alert status of many departments has been raised. Ankara, in fact, believes it has rights to the area south of Kastellorizo as part of its continental shelf, while Athens has always strongly denied it, denouncing a violation of its territorial waters. The notice of restriction of navigation in the area (Navtex) launched by Turkey for research, therefore, is seen as a serious threat to Greek national sovereignty over that stretch of sea, but not only. An arm wrestling which is potentially explosive and which can seriously challenge two countries still formally allied.

And, given that we are talking about marine resources, how can we forget the long arm wrestling between Turkey and ENI for extraction rights off the south-east coast of Cyprus where Ankara, in an intimidating move and without legal basis , prevented the drilling, regularly authorized by Nicosia, by the ship Saipem 2018 in 12000. In that case, the Turkish political will expressed itself by navigating its military ships in the waters assigned to ENI, preventing it from carrying out its operations and forcing it to give up the search for hydrocarbons in that area.

To these serious reasons for litigation between the coastal countries is added the proclamation of an exclusive economic zone of 400 miles by Algeria which, in a sea as small as the Mediterranean, means having been granted the right to use marine resources up to at the limit of the Spanish (Ibiza) and Italian (Sardinia) territorial waters, in contravention of article 74 of the UN convention on the law of the sea. The Algerian authorities have declared their willingness to discuss it with Italy, but the fact remains, as is the certainty that it would have been better to start consultations before that unilateral act.

Broadening the horizons, another area of our strategic interest is represented by the Horn of Africa and by what happens both on the sea, where the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb represents a very important transit point for merchant ships to the Red Sea. , the Suez canal and the Mediterranean, both on land, where the reasons for conflict between the countries of the area are rooted in ancient disputes and new reasons for opposition. One of these is water, an essential asset for the life and activities of the area. In 2011, for example, the Ethiopian government began building a giant dam on the blue Nile.

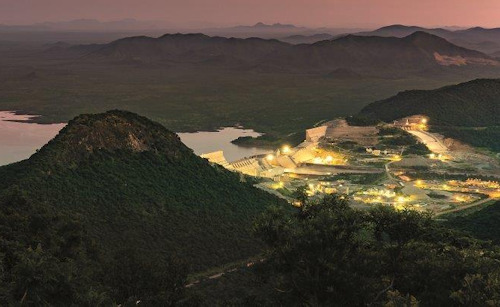

La Grand Renaissance Dam (photo), whose construction was entrusted to the Italian firm Salini-Impregilo, once completed it will operate the largest hydroelectric power plant in all of Africa, guaranteeing the country's energy independence and further gain through the sale of the surplus. It is therefore evident the importance that Ethiopia assigns to the monumental work located about 15 kilometers from the Sudanese border. The water coming from the Ethiopian highlands along the course of the blue Nile ensures about 80 percent of the average flow of the Nile which, in the summer months, becomes almost all the water that flows to the estuary located, as is known, on the Mediterranean coasts of Egypt.

It is therefore an imposing work which, by touching primary goods, has triggered political, economic and environmental controversies and doubts. Frequent complaints, currently limited to political and diplomatic spheres, however, risk lighting the fuse which could cause much more fiery conflicts. In this period, in fact, with the construction of the dam now reached about three quarters, the progressive filling of the reservoir is being planned, which will have a final capacity of 74 billion liters of water. This means that the water needed for the operation will be subtracted from the normal flow of the river, causing a significant decrease in the usability of African countries downstream of the dam, more precisely Sudan and Egypt. A decrease that is added to the water depletion already in place for some time and depends on both the large withdrawals for agricultural, urban and industrial use, and on an overall decrease in the rainfall recorded in recent years in that basin, which supplies water to over one hundred million inhabitants, all dependent more or less directly from the Nile. Cairo, believing that a filling carried out rapidly could cause an insufficient flow rate during the summer months and a consequent serious water, economic and social emergency to the populations, strongly asks that the filling take place very slowly and that it affects a period of not less eleven years old, preferably fifteen. Ethiopia, on the other hand, having the need to start hydroelectric production as soon as possible, is planning to fill the basin in a significantly shorter period, between four and seven years.

The issue has important national security implications for Egypt, an essential country for the maintenance of regional balances in the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Near East, so much so that, in the absence of a position taken by the The African Union, in support of Cairo, both the United States and China took the field, the latter also with a view to a progressive increase in its influence in East Africa. The intransigence of Addis Ababa, however, risks dragging the entire region into a dispute with unpredictable results, which has already seen President al-Sisi address a strong letter to the UN Security Council, with which he says he is ready to defend the reasons of Egypt by any means. A letter that could represent a first step on the road to possible muscle actions. For his part, the Ethiopian chief of staff responded by deploying the army and missile batteries to defend the work. All this worries and interests us, because it takes place in a part of the world already afflicted by enormous political, economic and social problems, which does not need any further tensions, which risk triggering a water war in the region that would have inevitable repercussions. political and economic also on Mediterranean countries.

Returning to the waters of the house, Egypt is also engaged in contrasting the aggressive Turkish expansionist policy. With this in mind, Cairo offered a diplomatic bank in Athens on the issue of oil research underway in the waters of Kastellorizo, thanks to its influence on the Arab-Islamic world, within which Egypt has been able to carve out a mediator role. credible, while maintaining a fairly uncompromising policy with regard to national interests. An Arab-Islamic world whose support is indispensable to Turkey in order not to remain isolated and to be able to successfully pursue the neo-Ottoman expansionist policy that characterizes this historical period. The recent Turkish decision to convert Hagia Sophia into a mosque is part of this framework, a highly symbolic choice with a high geopolitical significance. However, Erdoğan's attempt to compact the whole Arab-Islamic world around this decision does not seem to have had the expected effect. This was, in fact, divided between supporters (catalyzed around Qatar, Libya and Iran) and denigrators of the measure (gathered around Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), highlighting once again the regional reference block and the rift existing between pro-Islamist countries and those hostile to political Islam. The provocation also reinvigorated the calls to free the al-Aqsa mosque (in Jerusalem) from the hands of the Zionist usurpers and risks reviving the already known devastating political-religious fire in Israel.

Returning to the waters of the house, Egypt is also engaged in contrasting the aggressive Turkish expansionist policy. With this in mind, Cairo offered a diplomatic bank in Athens on the issue of oil research underway in the waters of Kastellorizo, thanks to its influence on the Arab-Islamic world, within which Egypt has been able to carve out a mediator role. credible, while maintaining a fairly uncompromising policy with regard to national interests. An Arab-Islamic world whose support is indispensable to Turkey in order not to remain isolated and to be able to successfully pursue the neo-Ottoman expansionist policy that characterizes this historical period. The recent Turkish decision to convert Hagia Sophia into a mosque is part of this framework, a highly symbolic choice with a high geopolitical significance. However, Erdoğan's attempt to compact the whole Arab-Islamic world around this decision does not seem to have had the expected effect. This was, in fact, divided between supporters (catalyzed around Qatar, Libya and Iran) and denigrators of the measure (gathered around Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), highlighting once again the regional reference block and the rift existing between pro-Islamist countries and those hostile to political Islam. The provocation also reinvigorated the calls to free the al-Aqsa mosque (in Jerusalem) from the hands of the Zionist usurpers and risks reviving the already known devastating political-religious fire in Israel.

On the land front al-Sisi has also recently threatened a wide-ranging armed intervention in Libya, in support of General Haftar, should al-Sarraj's troops, supported by Erdoğan, go beyond Sirte.

As can be understood from these examples, but it has been so for more than two thousand years, fundamental national interests gravitate around the Mediterranean. Whether we want to recognize it or not, globalization has multiplied the volume of international trade, which takes place mainly by sea. It is for this reason that the century we are going through has been defined as the blue century. Any crisis or conflict in this strategically fundamental area therefore risks having serious repercussions on the freedom of navigation and maritime safety, with important implications on the economies of the coastal countries, already severely tested by the Covid-19 pandemic.

As can be understood from these examples, but it has been so for more than two thousand years, fundamental national interests gravitate around the Mediterranean. Whether we want to recognize it or not, globalization has multiplied the volume of international trade, which takes place mainly by sea. It is for this reason that the century we are going through has been defined as the blue century. Any crisis or conflict in this strategically fundamental area therefore risks having serious repercussions on the freedom of navigation and maritime safety, with important implications on the economies of the coastal countries, already severely tested by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Indeed, the alignments in the broad Mediterranean and the enlarged Mediterranean are changing with unprecedented rapidity in recent history and with reversals in the face that do not predict the achievement of credible stability in a short time. The facts are numerous and far-reaching. The failed coup in Turkey in July 2016 brought Ankara closer to Tehran and Moscow, accelerated the breakdown of Kemalism, highlighting the fragility of the Anatolian country and delivering absolute supremacy in internal leadership to an Erdoğan who started a policy assertive foreign as never happened in the Turkish history of the last hundred years. All this also definitively wrecked the negotiations for Turkish accession to the European Union, which formally started on 3 October 2005 but never really took off in substance, interrupting the progressive and constant process of Turkish rapprochement with Europe, which began in 1923, with the birth of republican Turkey. A process that had led that young republic to adopt the Swiss civil code, the German commercial and Italian penal code, to accept the Gregorian calendar and the Latin alphabet, to transfer the weekly day of rest from Friday to Sunday and to recognize the right of women to active and passive voting (in 1934, ten years earlier than in France).

At the same time, North Africa and the Near East, in which some asperities between Palestinians and Israel had been mitigated (but were far from resolved) and reduced the Mediterranean role of the self-proclaimed Islamic State, which moved to sub-Africa -Saharian, two unscrupulous opponents face each other in the Libyan desert, in a fight at the moment at the tip of the foil, but which risks continuing to slash, with the danger of involving many other actors in the clash.

And so, while Italy is experiencing a complex political season in search of new European balances, in a context deeply marked by the crisis related to the Covid-19 pandemic and by the repercussions of international events, which have further compromised the stability of the Mediterranean region Enlarged, in which we are deeply inserted, diplomacy is trying to make our country recover the international and Mediterranean role it deserves.

And so, while Italy is experiencing a complex political season in search of new European balances, in a context deeply marked by the crisis related to the Covid-19 pandemic and by the repercussions of international events, which have further compromised the stability of the Mediterranean region Enlarged, in which we are deeply inserted, diplomacy is trying to make our country recover the international and Mediterranean role it deserves.

However, alongside diplomatic initiatives, the application of a foreign policy that also makes use of a credible naval diplomacy, implemented by an efficient fleet and operationally capable of protecting national interests on the sea, mainly in terms of law, but indispensable even being ready to show muscles, if indispensable. It is important to be aware that foreign policy is above all an exercise in relationships, both within the context of values to which, by history, culture and positioning choices, each country feels it belongs, and in relations with realities that often carry their own values. and not necessarily coincident. In essence, in a context of worrying deterioration of the international situation, which sees the emergence of circumstances and behaviors that weaken those which until now we have been used to considering stable anchors of our international politics, more initiative and more energy is needed in forming alliances and in liming the global geopolitical stage, adopting the most appropriate political strategies for the promotion of national interests and their defense in an environment in continuous evolution.

Finally, the road to achieving a credible balance in the Mediterranean cannot disregard the involvement of the United States, allies and friends whose support is indispensable to us but whose attention is currently focused mainly on the Pacific Ocean and China, and Russia , a country with which we have friendly relations but, above all, for its close relations (including supply of armaments) with Turkey, thus measuring the real will of the two powers to contribute to a shared stabilization of the Mediterranean, corresponding to a primary interest national team of Italy.

cv pil (res) Renato Scarfi

1 Francesco Sisto, The battle of Abukir (1798) and the strategic role of the Mediterranean - Online Defense 26 May 2020

Photo: Türk Silahlı Kuvvetleri / Vessel Finder / Webuild / US Navy / Prime Minister's Office