It often happens that to understand the origins of a conflict, as to understand where an evil comes from, one must investigate until the triggering cause is found: a decisive event that caused it. For a person, for example, possible hereditary diseases are traced, while the only plausible way to understand a nation is to research its history. Then everything becomes clearer because when we talk about war between two countries, history offers the most suitable key to understanding the reasons.

The war in Ukraine has displaced Europe which, although it lives a peaceful daily newspaper, cloaked in even abstruse treaties and principles dictated by the Union, in other places this is not true and secular bitterness takes over. We saw it happen in the Balkan countries in the XNUMXs and we see it again today in Ukraine.

The modern age was an era that sowed many discords, some dormant for centuries, others more latent and always ready to rekindle. Ukraine is certainly one of these cases where the hatred between the Ukrainian and Russian people has deep roots, dating back at least to the eighteenth century and perhaps even earlier.

In this story we will focus on what happened in the eighteenth century and in particular at the battle of Poltava in 1709 which forever changed the games of force in Eastern Europe.

Dominant Sweden and growing Russia.

Among the greatest leaders in history, Gustavo Adolfo of Sweden played a predominant role in the events of the seventeenth century. Under his wing, Sweden evolved in all fields, especially in the military.

A wealth of experience gained in the Thirty Years War which, subsequently, became a hereditary mark for all Swedish kings: from Charles X onwards the rulers of Stockholm were able to expand and maintain their domains at the expense of the various populations of the Northern Europe.

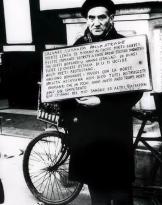

Denmark, Poland, Saxony and Russia attempted to oppose such aggression, however Charles XII (portrayed) quickly silenced his opponents by defeating them in a series of battles in what everyone remembers as the Great Northern War.

In 1705 the king of Sweden forced Poland to peace after taking Riga (1701), Pulutsk (1703) and Grodno (1705) from it. The following year he fell to Saxony, which after the battle of Fraustadt was led back to milder advice.

The most important one was missing from Charles XII's book of victories: Russia. In 1700, when the Northern War broke out, the young Swedish king (he was just 18 years old) inflicted a severe defeat on Peter's army which was not yet ready to face the army heir to Gustavo Adolfo.

After the victory of Narva, very imprudently, Charles XII turned his back on Russia, considering it a very lowly adversary and worthy of little attention. Peter, however, unlike the Swede, was a more mature ruler, but above all culturally prepared and attentive to what was happening in the West. Already as a young man he developed a military vocation that even allowed him to have a small army (poteshnye) created for his war games1. Peter ferried harsh Russia from a semi-feudal retrograde regime to an evolved and rich state, where the nobility no longer languished in the heat of the palaces, but was actively involved in the management of the government and in the military establishment.

The army of Peter the Great was reformed, the old units were replaced by more modern regiments with officers of Russian nationality. Among his most valid commanders we remember Prince Alexander Menshikov (1673-1729) who, as a boy, had served in the small army of Peter and Count Sheremetiev, an admirer of the Tsar's reformism.

Between the two contenders - Russia and Sweden - there was a third actor, Ukraine or otherwise known as the land of the Cossacks where Ivan Mazepa (or Mazeppa as used by Westerners) could really act as a tip of the balance.

THEEtamanate Ukrainian

THEEtamanate Ukrainian

Ivan Mazepa (portrait) was one of the most controversial figures in Eastern Europe. In 1700, Mazepa was the Hetman (Ataman) of the Cossack army Zaporozhians and exercised absolute power over the eastern part of Ukraine. Some historians dubbed this slice of Ukrainian territory the Etamanate given its territorial consistency and the influence it had with respect to the neighboring states: the dominion of Muscovy, the union of the Polish-Lithuanian confederation and the numerous vassals of the Ottoman Empire such as Moldavia and the Crimean Khanate2.

We were therefore faced with an extremely disorganized reality, where the Ukrainian population was permeable to various cultures. For a long time the Cossacks of Ukraine served the Muscovite principality, but when the war with Sweden broke out, Ivan Mazepa drastically changed course, choosing to ally with the Swedish ruler. It was a sensational action, which led to the damnatio memoriae on his name and was a harbinger of misfortune for the Cossack population of Ukraine. Mazepa's betrayal caused, in fact, a rift within the Cossacks because as soon as Peter heard of his turnaround he appointed another Ataman leader, Ivan Skoropads'ksi3.

The advent to the throne of Peter and his imperial ambitions canceled forever the dreams of Mazepa who yearned for the constitution of a great Etamanate Cossack with its borders extended to the western part of Ukraine. The reforms implemented by Peter spread to Ukraine, effectively eroding the power and prestige of Mazepa: this was the reason why Ivan threw himself into the arms of Charles XII.

In 1708, when the betrayal was now plain for all to see, Peter took the offensive against the traitor, conquering Baturyn, the capital of Mazepa. The Ukrainian chronicles described the conquest of the city, denouncing the horrible massacres committed by the Russian army; for his part, the Tsar obtained an important moral victory that led the undecided Cossacks to side with him.

With the alliance of Mazepa and a good part of the Cossack knights, Charles XII studied a plan to decisively strike the opponent. There were few paths to follow: advance north towards St. Petersburg, or directly towards Moscow or go south into Ukraine where the Swedish ruler had Mazepa as an ally. The first option was risky, as it would turn Swedish Livonia into a battlefield; the best plan was perhaps to point towards Moscow, via Smolensk - the same route that Napoleon then took in 1812. Peter was however convinced that the Swedish army would advance towards St. Petersburg also because Charles confided to General Lubecker the execution of diversionary maneuvers from Finland.

The Battle of Poltava

Something in the events that followed the conquest of Poland and the advance into Russia forced Charles XII to change his plans. Certainly the decisive factor that messed up the Swedish king's plans was the "scorched earth" tactic adopted by the Russian army which, during the retreat, was careful not to leave something to the enemy.

Something in the events that followed the conquest of Poland and the advance into Russia forced Charles XII to change his plans. Certainly the decisive factor that messed up the Swedish king's plans was the "scorched earth" tactic adopted by the Russian army which, during the retreat, was careful not to leave something to the enemy.

Peter understood that Charles XII had no intention of threatening St. Petersburg, but rather of heading towards Moscow by passing through the so-called "river gate" between the upper courses of the Dvina and the Dnieper and not from the Baltic countries4. Overcoming the warlike details, Charles XII tried several times to force the blocks that the Russian army had erected in front of the capital: the nature of the terrain and the difficulty of supplies thus forced Charles XII to a halt, but above all to reconsider his plans. The light came to him from Ukraine, when Ivan Mazepa openly declared himself available to an alliance against Peter.

Ukraine had everything it needed to feed the Swedish army and would provide excellent winter quarters. Furthermore, Charles XII hoped to obtain substantial military reinforcements from the Ukrainians, neighboring Poland and Turkey. On 11 October 1708 the king of Sweden marched in the direction of Ukraine beating the Russians at Romny, Gadyach and Lokhvitsa: but he seemed to have fallen into a trap. The icy winter of the Ukrainian lands had crystallized the Swedish army, forced to disperse to find refuge in the villages; Peter's cavalry, on the other hand, watched over the enemy's movements, sensed their desperation, always being ready to repel the attacks on Kharkov and Kursk.

With the arrival of spring, Charles XII's army was in the vicinity of Poltava, anxiously awaiting further reinforcements from Poland. Meanwhile, Prince Menshikov's Russian troops concentrated in Vorskla, right in front of the Swedish deployment.

The battle began according to a classic siege pattern: the Swedes began digging trenches in front of Vorskla, while Russian skirmishers struck to isolate the opposing troops.

In June, Tsar Peter himself arrived on the battlefield and decided to attack in the direction of Poltava: he enjoyed an undoubted numerical superiority. The battle was a complete success for the Russians who achieved a landslide victory against Charles XII.

The Mazepa Cossacks fought to the fullest of their strength, however their courage was not enough and at the end of the war they were overwhelmed by the avenging fury of the Tsar. The surviving Cossacks - according to a precise order from Peter - had to be brought before him which meant certain death. On June 31, 1709, some 20.000 Swedish soldiers from Ukraine were taken prisoner and then released in 1721, only after the contenders signed the Nystadt Treaty. Charles XII, on the other hand, had fled to the borders with Turkey.

Mazepa the damned

Poltava's victory forever changed the balance of power in Eastern Europe, effectively erasing the Swedish hegemony that had lasted for nearly a century. Peter I the Great in turn became the predominant force, placing himself on a par with other Western powers.

As for Mazepa, his betrayal had such an important echo that the anathemas of the ultra-Orthodox church resounded until 1959.

Tsarist propaganda pushed so that hatred towards Mazepa never fell into oblivion: Peter emphasized how the Cossack was hostile to the Orthodox Church and pushed Ukraine towards Polish Catholicism5. In this sense, the propaganda work was carried out by the clergyman Teofan Prokopovych who, in his work dedicated to Peter the Great - History of Imperator Peter Velykogo - increased the dose by stating how Ivan hated Russia and was devoted to Poland. According to Theophan, the Cossack was not fighting for independence, but rather to cede Ukraine to the Polish confederation.

The echo of Mazepa's infidelity also reached other countries where the tsarist censorship was unable to veto any; yet in Germany and in Saxony the gesture of revolt was interpreted negatively and the monarchies were in solidarity with Peter.

Among the most prominent views on Mazepa's behavior was that of Voltaire who, in his keen analysis, showed sympathy for Charles XII and Sweden. Not surprisingly, after the war, many Ukrainians and Swedes sought refuge in the homeland of the philosophers. According to Voltaire Mazepa was a "courageous, enterprising, indefatigable [...]" man who had remained at the side of his ally until the very end.6. Voltaire also stated that Ukraine had always sought freedom, far from the Muscovite influence as well as from the Polish and Ottoman ones: "First of all it placed itself under the tutelage of Poland which treated it as an employee, so it they gave to the Muscovite principality who did his best to subjugate it "7.

There is therefore a controversial story that places some limits on the "nationalism" waved by the Ukrainians. The fact is that today we are faced with events which have very deep roots, although everything appears to be a plan hatched by Tsar Putin.

Indeed, already in the modern age Ukraine has always manifested a marked anti-Russian sentiment with a view to a longed-for autonomy: this pushed it towards the frantic search for some ally who could guarantee it, without wanting anything in return. This was not the case and it still seems impossible to claim it today. So let's see how the extermination perpetrated by the Russians in Baturyn resembles that of today and of Bucha and how Zelensky resembles in some ways Ivan Mazepa.

One wonders if the other actors who are treading the stage of this international crisis are ready to act as Charles XII did, although the result of this intervention could turn into a dangerous second Poltava.

1 A.Konstam, Poltava 1709. Russia comes of Age, Osprey, London, 1994, p. 9.

2 TM Prymark, "The Cossack Hetman: Ivan Mazepa in History and Legend from Peter to Pushkin", in The Historian 2014, p. 238. URLs: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/hisn.12033.

3 S. Plokhy, «Poltava: The Battle that Never Ends», in Harvard Ukrainian Studies, Vol. 31, n.1.4, 2009-2010, p. xiii.

4 A.Konstam, Poltava, cit., pp. 34-35.

5 TM Prymark, The Cossacks, cit., p. 239.

6 Ivi, p. 243.

7 Ibid.