In the ancient world the military career had a greater importance than it has in our time, certainly it gave rise to greater comfort; this is logical if we consider that the lack of powerful weapons accentuated the function of the human element.

Another element to consider is the influence of the Imperialist States in considering war as an ideal that was worthily represented in the artistic figurations and in the stories handed down to posterity.

A clear example of this concept was the Assyrians whose palaces were teeming with warlike representations that celebrated the conquests, all accompanied by the inevitable "annals" that told the scenes described therein in words; in one of these the king Asarhad in the 671 AC described the conquest of Egypt:

"I laid the assault on Menfi the king's residence, and I conquered it with wells, tunnels, and assault stairs, I destroyed it, demolished its walls, burned it with fire. The king's wife, the women of his palace, the heir, the other sons, the possessions, the horses, the immense quantity of cattle I took away as booty in Assyria. All the enemies I brought from Egypt, leaving not one to pay homage. Everywhere in Egypt I appointed new kings, governors, officials, maritime inspectors, officers and scribes. I imposed the tribute upon them as the Supreme Lord, an annual and uninterrupted tribute".

The violence of war is accompanied by an infinite cruelty with capital punishments, sentences to forced labor and the enslavement of women; the goods were usually confiscated and distributed among the victorious soldiers.

The economic aspect is extremely interesting, explains why the military career was sought after; from ancient Egypt comes the direct testimony of Ahmose, a soldier who participated several times in the division of the proceeds of war and got rich by collecting slaves, cups and necklaces.

His fellow soldier Nebamon received from the Pharaoh a two-storey house with a courtyard shaded by palm trees, flocks, servants and a large land cultivated by slaves.

The Pharaohs evoked these merits in their inscriptions, as did Ramses II when abandoned in Qadesh in a tone of reproach so he turned to his men:

"How vile your soul or my knights are! Did I not fill my heart with you? Isn't there one of you that I didn't do good in my land? Did I not behave like a sovereign when you were poor? I made you great for my merit, day by day. I put my son in his father's property, removing evil from the land of Egypt. I exempted you from taxes and gave you more loot. I have satisfied anyone who asked for a wish. There is no sovereign who has done for his army what My Majesty has done for you".

The living conditions of the military of these eras were much worse than the life that took place in the city, the earnings compensated for the sacrifices; until now a satire of an Egyptian scribe describing the lives of men of war has remained:

"He is awakened at an hour in the morning. They stand at his feet like a donkey and make him work until sunset. He is hungry, his body is torn, he is dead while still alive. Face long marches in the hills, drink fetid water every three days, with a taste of salt. His body is destroyed by dysentery, if he manages to escape he is undone by the marches. Whether in the neighborhood or in the country, he is always unhappy. If he escapes and goes with the deserters, all his people are put in prison. When he dies on the edge of the desert there is no one to pass on his name".

We are witnessing a slow evolution of weapons of war, the finds are full of warlike representations with swords, spears, shields and bows; around the middle of the second millennium BC horses and fast war chariots were introduced, conceived by the Hittites and adopted by Egyptians and Assyrians; rams and catapults were the forerunners of firearms that marked a profound change in the techniques of war.

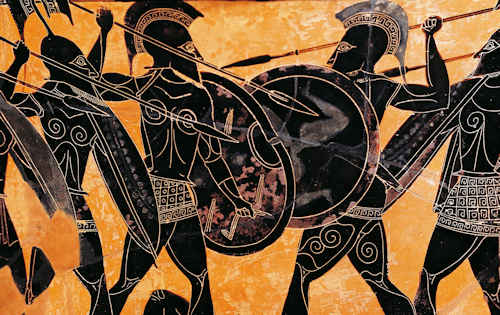

After the Egyptians also the Greeks illustrated in great detail the war stories of their own people, the Iliad handed down to us events, uses and customs of the Greek warriors; what distinguishes them is the typical phalanx array, already used by the Sumerians, supported by knights and archers.

After the Egyptians also the Greeks illustrated in great detail the war stories of their own people, the Iliad handed down to us events, uses and customs of the Greek warriors; what distinguishes them is the typical phalanx array, already used by the Sumerians, supported by knights and archers.

The Greeks created the most imposing marine fleet ever seen until then and the defenders of Athens were moved by very solid ideals which they pronounced loudly in the temple of Aglaura:

"I will not dishonor the sacred weapons I carry. I will not abandon my combat partner. I will fight for the defense of the sanctuaries of the State and I will transmit to posterity an undiminished homeland, but greater and more powerful, in the measure of my strength and with the help of all. I will obey the magistrates, the constituted laws and those that will be constituted. If someone wants to overturn them, I will prevent them with all my strength and with everyone's help".

These are very significant words even if the establishment of mercenary troops is generally attributed to Greece. The phenomenon already abundantly present in Israel with Saul and David who found small armies of fortune is expressed in Greece in the form of guards deputed to the personal protection of notables and officers.

Only centuries later the mercenaries will spread on a large scale, affirming the specialized military corps where the gain replaces the value and the ideal of the homeland as a stimulus.

The greatest tribute to the ancient arts of war comes from Italy; already the pre-Roman civilizations have left evidence of their own art of war that can be deduced from the discovery of helmets, armor, shields, greaves but it is with Rome that the war organization touches its peak.

First and foremost, serving the Empire was considered an advantage and a privilege given that enrollment gave the right to a basic salary that went up from the 225 denarii of the Giulio-Caludi to the 750 of Caracalla; in addition there were the extraordinary distributions of money for the elections of the emperors, the parties and obviously the victories.

The Roman system had a peculiarity, the sums were disbursed to the person entitled at the time of the leave, except for the small common expenses, in a sort of forerunner fund-pension of the present day.

The soldier also received a special prize of 3.000 money or the equivalent in land, but the harshness of daily life abundantly justified these privileges; remains to us the writing of Tacitus on the commander Corpulone:

The soldier also received a special prize of 3.000 money or the equivalent in land, but the harshness of daily life abundantly justified these privileges; remains to us the writing of Tacitus on the commander Corpulone:

"He kept the whole army under tents, although to plant them he needed a digging job in the ground that was covered with ice due to the harsh winter. Many had frozen limbs, some sentries died numb. A soldier carrying a bundle of wood had his hands frozen to the point that they remained attached to the load, leaving his arms limp. The general, dressed lightly and uncovered, was always present in the marches and works; he gave praise to the brave, comfort to the sick, an example to all. Therefore since they refused to endure the rigor of the climate and of the service, they sought for remedy in severity, not forgiving the blame for the first and second time, as in other armies, but punishing immediately with death those who abandoned the insignia. This remedy proved to be effective".

However the condition of the Roman soldiers was better in the periods of military anarchy, in correspondence of the elections of the emperor or the recognition of their illegitimacy; in these periods the soldiers made every sort of anguish to those who were forced to host them.

The mercenaries, unknown in the most ancient Roman order, make their appearance in the last phase contributing to the irreversible crisis of the Empire, undermining its operational capabilities in the military sphere; centuries will pass before someone will match those pages of history.

(opening image: Michele Marsan - others: web)