Waters of Poreč, Istria, dawn on November 8, 1916. Dense fog. Cold and moisture penetrate the bones through the leather jackets. Shiny with water and lined with lamb. As usual, there is no trace of Austro-Hungarian ships. In the Upper Adriatic, they have not been seen during the day since May 24, 1915. The dominion of the sea is absolute on the Italian side. There have been, up to that moment, only 4 short firefights between our torpedo boats and their minesweepers, all in the Gulf of Trieste and ended with the sinking of a couple of small units and pontoons of the k. (u.) k. Kriegsmarine. Little war. It's different at night. The Austro-Hungarians come out protected from the darkness, quickly cross the Adriatic, briefly bombard some coastal towns in Romagna or in the Marche without defenses and retreat. Six times they were intercepted by Italian fighters and torpedo boats, but these are rare cases. It is day now, even if almost nothing is seen, and the mission is simple. Driving 6 seaplanes from the sea, 8 of them French, sent to bomb Poreč. Two squadrons of torpedo boats of the Regia Marina, supported by the Nullo and Missori fighters, form a sort of arrow in the sea to show the planes where to go. This is all very primal, but neither hydro nor torpedo boats have a radio. Only the two fighters are big enough to board an RT station

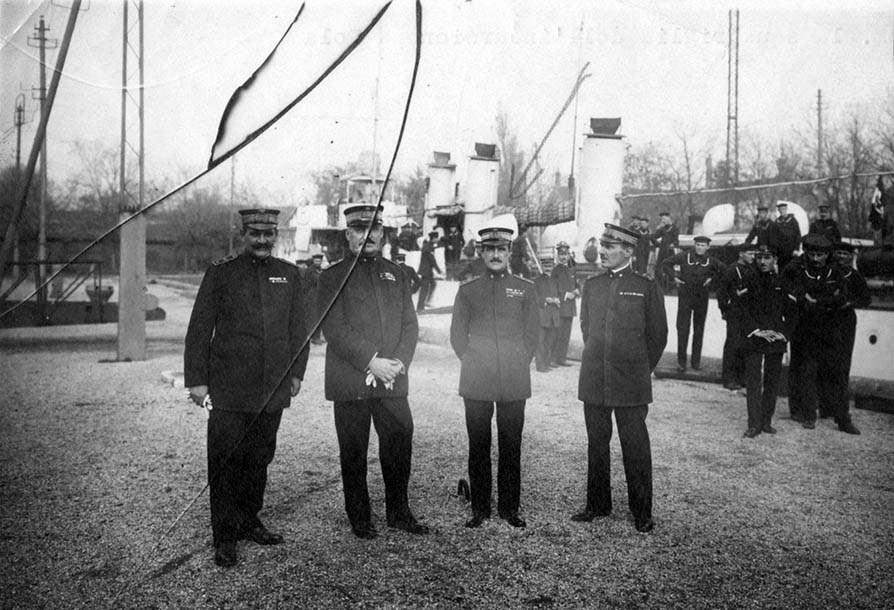

Italian and French planes arrive and bomb the Porec seaplane base. The reaction is not long in coming. Four Lohner hydro patrols drop about twenty bombs on the Italian torpedo boats and then attack the enemy aircraft. The ships get away without damage, but a French FBA, reached by the engine, is forced to land. The formation torpedo boat, the 9 PN of the corvette captain Domenico Cavagnari, intervenes (opening photo).

An excellent sailor with a bad character and short stature, Cavagnari already distinguished himself a week earlier, when he lowered at night, with his small 120-ton ship, the obstructions that protect the Fažana Canal, thus allowing the MAS 20 of Commander Ildebrando Goiran to torpedo, in the absence of other targets, the old guard ship Mars. The weapons did not explode and the Austro-Hungarian unit got away with two small waterways. Cavagnari remained under obstructions all the time and recovered the MAS and finally returned to the base. A silver medal (the second) is being granted motu proprio by the king.

Today it is different. The French are recovered and the seaplane is towed. The other Italian units are already distant, somewhere in the fog, after the air attack just before. The 9 PN proceeds, at this point, at forcibly reduced speed, expiring even more, when a trace of sun appears through the fog. And there are also 3 Austrian torpedo boats that immediately put the bow on that easy prey. The distances are rapidly reduced and soon one can read the Arabic numerals painted on the bow mascons: 1, 2 and 4. They are modern subtle units equivalent to the 9 PN. The 29 sailors of the Italian torpedo are waiting for the order to let go of the trailer and leave at full speed. Cavagnari, on the other hand, is silent. We are less than 5.000 meters; as soon as it reaches 3.000 the solitary 57 mm piece of the torpedo boat will have to start the duel with the six 47 mm guns of the opposing ships. 4.000, 3.000 and then, suddenly, the subtle Habsburg units pull out and carry under the batteries of Poreč. They will later say in the report that the Italian ship was the Quarto, weighing 3.300 tons.

The trailer continues and the 9 PN arrives in Venice in the afternoon with its plane on a leash, intact except for a bullet that has cut off the fuel supply, and with its two pilots still in disbelief. The news, immediately released by the rumors of the bow, is that the little lieutenant captain said to the aviators "J'ai refusé da payer avion, voilà c'est tout". It is a legend, but Cavagnari's stinginess is equally proverbial. More Genoese than Genoese, Mingo, as he has been nicknamed (by Domenico) since the time of the Academy, is a bachelor, but he certainly does not lead the brilliant life of several of his colleagues in Venice and, above all, on the Lido. Son of a little pharmacist, he sends everything home, always wears a uniform, wears only military shoes and thinks only of the service. The only known weaknesses, the taste for chocolate and for the sfogio, the steamed sole of a tavern near the Scalzi bridge. Everyone thinks he's stingy; in reality he sends the money (the salary, as reported on the matricular sheet, amounts to 5.000 lire per year, a few even for the time) to an invalid sister and arranges for the rest.

On the evening of November 8, however, the problem is another. Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel, Commander-in-Chief of the Upper Adriatic and the square of Venice, summoned him on the spot. Risking a torpedo boat, with 30 men and costing 100.000 lire, for an empty plane worth less than 1.000! Thaon di Revel's famous doctrine of calculated risk has been violated in full by that presumptuous lieutenant captain. Too bad for him !, is the thought of the majority Hero or non-hero, this time the pay for all, including a certain missed round of glasses. As can be seen from the annotations made by Cavagnari and written on the edge of a page of the Maritime Magazine, many years later, the interview got off to a bad start.

The young Genoese officer, however, was no less than the admiral. He replied, in fact, observing that the story "of the plane I'll pay for it" is nonsense and that he acted knowingly to finally arrive at a confrontation with that elusive enemy. Cutting off the trailer was always in time. As for the cannon and the torpedoes, he would have seen it himself. The other Italian units were still within acoustic range, somewhere in the fog, and would soon arrive, guided by the explosions of the grenades, thus cutting the enemy out of their base. "I was expendable", he wrote for himself alone, "and the people and all of Italy needed a victory at sea". Thaon de Revel was struck by this impertinent young officer. On 22 January 1917 he appointed him second in command of the Maritime Military Defense of Venice. He was later sent back to sea, at the insistence of the person concerned, in 1918. Chief of Staff of Thaon di Revel, now Minister of the Navy, between 1922 and 1925, commander of the Academy in 1929, Undersecretary and Chief of Staff of the Navy between 1933 and 1940, Cavagnari was the father of the "Grande Marina" of the thirties and forties. He married, in 1938, the same girl of yesteryear who prepared his outburst in Venice, twenty years earlier, and who also washed his shirts. To save, of course.