Of these houses

he did not stay

that some

wall shred

Of many

that corresponded to me

he did not stay

not even much

But in the heart

no cross is missing

It's my heart

the most tortured country

Giuseppe Ungaretti, San Martino del Carso (Porto Buried, 1916)

On the anniversary and the remembrance of the Victory of 4 November 1918, we respectfully leave the word to witnesses - now silent yet so powerful - of the past, trying if possible not to take away the stories while we adapt the length to the short space of this address book1 and to the small screen of your smartphone. The writer has tried, as far as possible, to put the stories in chronological order from the beginning of the Great War up to those of the 1918 and beyond2.

In memory of the Flup beard and the grandfather Talin

It was the late summer of the 1983 and for some months I had come into the world, it happened that one afternoon I was with my mother from the paternal grandparents in whose house also lived the great-grandmother; looking at me in the face he said (in Piedmontese, since he did not speak almost Italian - it was 1893 class) to my mother: "A l'el barbarot me 'l beard Flup (trad:" has the chin - specifically the dimple in the frontal area - like Uncle Filippo ")." But who was the beard flup? The only thing that was known was the name, Rizzone Filippo, had left for the First World War and he never returned, all wrapped in a sort of mystery and modesty. One fine day, we are in the early years 2000, it happened that was found by myself a tin box placed in a closet held in a room used as "refugium peccatorum"; inside was folded a fold of newspaper with the photo and a short text in which was reported the news of the death. The years passed and we arrived at the 2015 when the commemoration of the Great War began and by pure chance I discovered that through the website of the Ministry of Defense there was the possibility to search for the names of the fallen through a search engine made available by the Commission for the Fallen Ones. I started the search and almost instantly found the information, at least the main ones, of the Flup beard: he was born in Montechiaro d'Asti in 1891, with the rank of simple Soldier was incorporated in the 3 ° regiment of the Alps and participated in the conquest of Monte Nero occurred on the night of 16 June 1915; following the wounds reported in combat, he breathed on the same Monte Nero the 3 July ... his war lasted little more than 40 days!

The great-grandmother who brought to mind the beard flup he had married a veteran after the war, also a simple soldier of the Alpini, Varesio Matteo (1894 class), known by all as Talin. Even though he had returned from the war, very little was known of him: my father only remembers some short stories, very rare and very incomplete, typical of those who saw and experienced wars, related to his participation in the events of arms for the conquest of Croda Rossa. The only thing he remembered often and with pleasure, especially when he met a friend, with whom he had left, had fought and returned home together, was that they went skiing ... probably belonged to some platoon / company of skiers, what that makes you smile if you think about what are the places and the social class of origin. The grandpa Talin he was awarded the Order of Vittorio Veneto in the early 70 years and peacefully concluded his life on earth in the 1975.

A Sicilian hero buried in Redipuglia

As requested, I would like to report the story of my paternal grandmother's brother. "Ignazio Bonvissuto soldier of the 1st Engineers Regiment born in Palermo on September 18, 1883 and died on the Karst as a result of injuries sustained in combat, he was recalled to arms on May 22, 1915. He left his wife and his work as a stone carver and after a short period of training was assigned to the front where he arrived on March 3, 1916. He took part in the 5th Battle of the Isonzo and after just three months on June 2, 1916 he was killed in combat by an Austrian grenade. His name is registered in the Golden Register of the fallen for the homeland and is buried in the military memorial of Redipuglia (GO) ".

The machine gun and the rosary

This is the story that my father Vincenzo Aliberti wanted to tell you. My grandfather was called Giallorenzo Pietro, he was born in S. Pietro al Tanagro (SA) the 29 in June 1895 and was called up in arms in February of 1915 with a station in Florence. He left for the front in force at the 85 ° regiment infantry brigade Venice (I keep his original leave). He fought along a good part of the Isonzo front and as he told me for more than a year he had been assigned to a machine-gun section and he himself had a French S. Etienne, explaining that he vomited up to 700 strokes per minute. He knew how to read and write and this involved him not a little with the other illiterate comrades. He was twice wounded on one shoulder and an ankle, which swelled to such an extent that after two days without proper assistance they had to cut off his boot. In the summer with very little water they were sometimes forced to drink their own urine with a single forethought ... let it cool !!! He did not eat any more rice for a lifetime and told me about the terror of the bayonet assaults during which they were urinating ... and not only !!! In the last years of my life I often found him wearing a rosary in his hand, sitting in the little house or hearth, reciting the short prayer of the dead for each grain of the crown ... I asked him why and for whom ... he told me that they were for every boy, and they were so many, that with that damn machine-gun he had "thrown" on the ground ... he never removed them from his conscience ... he said "they were Christians like me !!!"

Memories of the past.

I saw the article now and I remember my maternal grandfather Collina Sisto who fought on various Italian fronts during the Great War. If it could interest me I wrote and published about an hour and a half of narration in which he relates facts and places that saw him as an active participant in the events, both his personal and that of the entire contingent to which he belonged.

Father's heart

I would like to recall what my great-grandfather Elia Morassutto, corporal major of the 18th infantry regiment, thought about the front, who died on the Karst on 27 October 1917. When in May 1917, he learned that he had become the father for the second time of a little girl who failed never to see - my grandmother Ernesta - wrote to the family "I'm glad she's a child so she won't be forced to go to war". A small story of a great war.

We never knew where grandpa Elias was buried and only recently did we have a picture of him.

From Sicily to the former Yugoslavia passing through Caporetto

Pietro Vicari was born in Modica on April 7, 1883, son of Antonio and Giovanna Giurdanella with whom he had three children, of which only two survived early childhood. In October 1915, a few months after Italy's entry into the Great War, Pietro was called to arms and, leaving his family and his work as a farmer, on the 31st of the same month he arrived in a territory declared in a state of war (exactly at Chiopris in the province of Udine) where he was assigned to the 147th infantry regiment of the Caltanissetta Brigade. With this regiment he faced the terrible trench warfare on the Carso, between Monte San Michele and San Martino del Carso (November - December 1915); on the Carnic Alps near Timau (February - October 1916); again on the karst hell, in the sector between Nova Vas and Hudi Log - Boscomalo (November 1916 - January 1917); and finally on Mount Mrzli, along the Isonzo course between Caporetto and Tolmino (January - October 1917). On 24 October 1917, a few hours after the start of the Battle of Caporetto, while under the command company of the 147th infantry, the soldier Vicari was captured on the Mrzli by the Austro-German army that broke through the Italian front in that sector. starting the infamous route. Conducted as a prisoner in Germany, he probably passed through the large Lechfeld prison camp where he was assigned to a work company and sent to Serbia (a nation then occupied by the Germans) to work near the town of Semendria (now Smederevo), located on the Danube river just east of Belgrade. Hard work, exhausting shifts, hunger and hardship caused a progressive and inexorable physical deterioration and on February 25, 1918, after 4 months of imprisonment, Pietro Vicari died in the Semendria hospital at the age of 35. He was probably buried in the section dedicated to prisoners of the German military cemetery of Semendria (no longer existing) and today, 100 years later, his tomb is still unknown to men, but known to God.

A family in the midst of Italian history and ... battlefields

ROGGERO PIETRO, of Pietrabruna (IM) class 1894, military district of Sanremo, 1 ° Alpine regiment. The 11 September 1915 on M. Kukla (Rombon) fell into combat. My grandmother and two other cousins were given the name of this uncle.

Pietro's brother, AURELIO, was the father of this grandmother, who was killed in March 1945 by partisans in circumstances never clarified.

SILVIO GIORDANO, class 1919, always of Pietrabruna, paternal uncle of my mother, alpine, missing in Russia. He was seen for the last time by his brother Rodolfo, also alpine, in Albania.

My mother's name is Aurelia Silvia. His father, my grandfather Tenth, did not leave for a fever with the last contingent for Russia.

ANGELO SALVATICO, from Calizzano (SV), during the war '40-'45 carabiniere. It was on the French front. He had a motorcycle accident. In the barracks in Caraglio (CN), he escaped the fire of the same, and it was marked psychically.

Stories of life from the internal front during the Second World War

From the Pession reader, which we publish often. My homonym grandfather Sergio did not live the war as a partisan "hero" rather than as a soldier, but as an accountant and a commercialist at the Casalisteria Casalini in Faenza. Despite some moments of tension and without hypocrisy, I can rightly say that if it passed really well, despite everything. This company produced furniture and wooden houses, playing its part in the war effort. A crucial moment, Casalini passed it in 1943 with the fall of Fascism on horseback between raids on one side and escapes between the mountains on the other. One of the managers of the company, a South Tyrolean gentleman, perhaps from Merano, far from well-seen by the proletarian labor force, was the victim of a misadventure of the period. Pursued by the workers, animated by resolutions that were anything but peaceful, he thought well of taking refuge in my grandfather's house, at the time married and with a child (my uncle) of just four years. My grandfather, more accustomed to human relationships, compared to the detestable "master" of South Tyrol, on the contrary was well seen by the workers because, in times of war, exchanges of favor, a basket of eggs and chocolate for children, were worth as much as a name written on a pass, rather than life itself. A friend of many workers and their families, my grandfather, he confronted the warlike group in shirt sleeves and gave time to the fugitive to take the cats' route up the rooftops. It was not a heroic gesture, but a very daily one which unfortunately did not merit the gratitude of the "master", who, once the delicate periods had passed, would never recognize my grandfather the liquidation that the law owed to him as an employee. The story has taught me that if someone is pursued with such ardor, a reason must be there. Always speaking of gratitude my grandparents, at the time of the first bombing on Faenza, thought it wiser to give up the stunted comforts of the apartment in the city, to move into a wooden house far from targets and save the salvable by bringing the furniture more prized by Franciscan friars with the promise of returning them back to the arrival of better times and, God willing, still healthy and safe. All, or almost, crucial choices; besides, I'm here to write, while their house was completely destroyed by the Allied bombs. And the furniture? Safe from the Franciscans. Unfortunately, even though splinters have even just touched the brown clothes of these gentlemen, at the end of the games, when my grandfather returned to them to get back the goods, received only a blessing and the pain of those who had lost everything in the bombing. Knowing, though not personally, the fame of my grandfather's skilled merchant and the almost never disinterested activities of the friars, I would have reason to believe that the agreement was anything but one-sided, but in the end, as the friars said at the time, "It was already a miracle to be alive and for this we had to give thanks to ... bla bla bla". I can only hope that these goods have gone to really needy people, rather than in the study of some overweight religious. But fortunately my grandfather was still working for a cabinet that soon would have to recognize a lavish liquidation ... I would also like to tell of the "abduction" of my uncle by the Allies who came to free us. Expectations because the child, barely school age, while mother and father were desperate to look for him in vain, if it passed cheerfully on the knees of a Canadian soldier or Polish (I did not know). With the wind in my hair, and perhaps a lot of dust and gnats between my teeth, my very young Uncle Tino and two soldiers carried, with as little madness of ease, messages between Faenza and Cesena in a jeep, thus spending what, both for him , which for parents, will be remembered as an unforgettable afternoon in the open air.

Finally, a memory of a front on which millions of men and women have fought ...

The "centurinare" of Terni. From the memory of Emanuela Pierucci.

The "centurinare" of Terni. From the memory of Emanuela Pierucci.

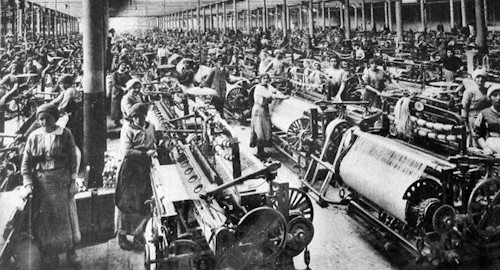

She was a woman like many others at the Jutificio Centurini in Terni.

Indeed a worker like many others.

Yes, because she was part of the more 1300 units (most women), too often forgotten, who, during the 15-18 conflict, contributed to the history of our people.

He had walked two hours in his shabby coat of brown wool with the wind whipping his face.

That day he would have worked twelve hours, with just one hour of break, he would have received a pay of 80 cents.

He had walked the tree-lined avenue before entering the factory.

The frost had woven inextricable textures, magical white spiderwebs.

A child's face in a woman's body.

She was twenty years old, with brown hair framing a face with an olive complexion, on which stood a broad and sincere smile, even when there was little to smile.

A handful of freckles gave her a beauty of the past.

He looked at the coarse-shaped boots for fear of having them too damaged during the journey: it had rained and the path was more bumpy than usual.

The socks of dark wool, coming down, shyly showed their legs slender and livid with cold.

At the age of twenty she was a mother, wife and daughter, ready to face terrible enemies: hunger, poverty, fear. He looked around for familiar familiar faces.

The peaceful exercise of the workers was entering the Factory: humble housewives, former peasants, housewives. He entered the factory with the muted 5000 melodies and the 300 frames of the factory already in his ears.

It would soon be another work day to produce bags for the defenses of the trenches at the front and jute fabrics. The poor health and safety conditions were the daily bread of the "centurinare".

So the Centurini workers were called to Terni, bravely ready to start deafening and dangerous machines. He looked up at an opening at the top, above his car. The timid light of dawn still did not filter through.

Dreams, for a few moments, took the upper hand in his mind, driven out by the first sounds of the machines operated by the workers. Next to her, a little girl from 13 was preparing for the frame.

She activated the machine that came from afar, which worked with the water from the Nerino Canal.

And his thoughts went to the other workers, to the other silent front of the nearby Regia Fabbrica d'Armi: storekeeper, machine tool drivers, electricians. At the exit he would find the darkness, but the real things in the dark no longer seem real than dreams. And she kept dreaming. The memory, we know, often hurts, but it's inevitable to rebuild pieces of our present.

Only the names ...

Finally, a thought goes also to Enrico Grandi (almost ten years at the service of the Homeland between the two world wars), Renato Bencini (colonel died on the Isonzo front), Flaminio Piccoli (politician and partisan during the last world war, that I had the honor to know) and Tranquillo Morini (ancestor of the writer).

In conclusion, the reflection leads us to pause, a moment, on the beautiful stories on the Great War of the reader Alessandra Panvini Rosati.

"It is a duty, for us who admire these peaks driven by pure aesthetic and mountaineering spirit, to think for a moment at least for all those who, 100 years ago, fought here and often did not return to the valley.

Different uniforms but same courage, same fears, same fate.

In the wind, I seem to hear their voices ... "

1 At most 200-250 words for reduce.

2 We believe we have spoken to everyone, just all the readers who wrote to us. If by chance an e-mail had not arrived or was lost, we apologize.