October 1918. Bad weather and rough seas. For two nights, on the 3rd and 8th of that month, an attempt was made without success, in front of Poreč, in Istria, to recover a couple of Italian informers active behind the Austro-Hungarian lines with a MAS. They have discovered important things, but the Hapsburg counter-espionage does not sleep and our people know they are being hunted down. The last carrier pigeon to arrive carried a very clear message.

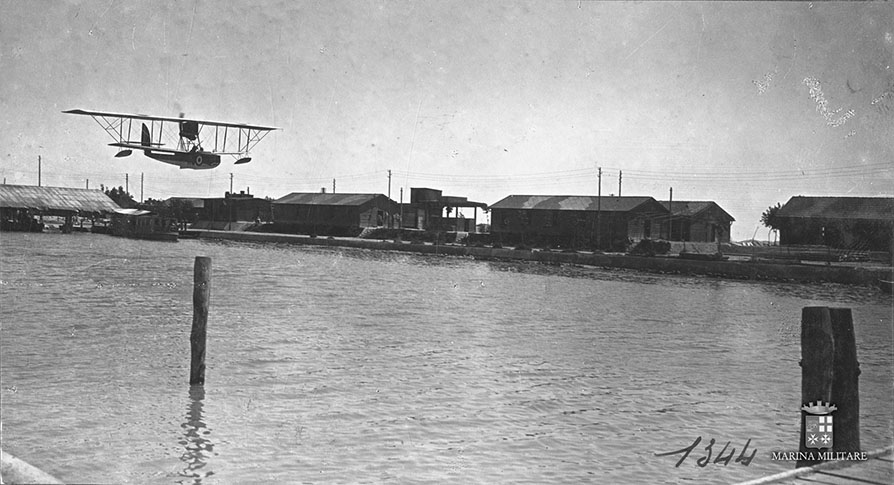

An attempt is made to bring them back with a small Macchi L.3 seaplane piloted by ship lieutenant Eugenio Casagrande, commander of the 253rd Squadron and specialist in such missions, with a dozen flights and night landings in the lagoon. On the 20th and 21st we begin by transporting two pairs of operators over the lines in order to prepare for exfiltration. The plane is sighted on the occasion of the second flight and shot, both Austro-Hungarian and ours. At night, you know, all cats are gray and the missions are covered by the utmost secrecy.

The Austrian counterespionage, the famous Evidenzbureau, has by now a sufficiently clear picture of the modalities of these operations in progress since June and knows even the name of the pilot. A poster with a size on its head is affixed, in perfect style western, on the walls of the houses of the Veneto and Friuli with the name of that solitary pilot, forced to do everything by himself, starting from the start of the propeller by force of arms, because there is no space for the second element of the crew, but only for passengers, pressed one on top of the other.

The 28 October the company is tempted and fails. Bad weather does not help and the informants, previously traced by one of the two Italian rescue teams, had to leave the agreed point whose characteristics, now standardized, were identified in time by the enemy, who executed immediately after a heavy mopping up . The 29 another pigeon arrives over the Piave; the other - with a copy of the encrypted message - was probably shot down by the Austrian rifle fire. Of course the modest code available to informants is not destined to last long under the cryptographic analysis of the Evidenzbureau. Ours are in the swamp of Villaviera, also hunted with dogs and about to be taken.

Casagrande volunteers by proposing a beautiful and good madness: to go during the day, so that he can be seen and reached even without a specific appointment. His life is at stake since the size, well known also on this side of the Piave, says that the sum will be paid even for the simple corpse of that sailor-aviator. However, there are other ghosts that emerge from the fog of those autumn days: Nazario Sauro, Cesare Battisti, Fabio Filzi and Francesco Rismondo, all hanged. It is the same fate that awaits those two who have been hiding for weeks in the mud and among the reeds.

The first landing occurs at dawn. The fugitives see it, but also the Austrians who take the hydro to shot. The plane is hit, but not in vital parts; only holes in the canvas that, fortunately, does not tear. The plane takes off and seems to be saved. For informants, it's over. But no. The L.3 returns, gliding and firing with the engine off. The surprise is maximized. The pilot will have two, maybe three minutes. Who will arrive first? The one or the other? Casagrande's hand is on the gun and at a certain point he gets up and takes aim because there are three shadows, muddy and unrecognizable, that come running and stumbling, but there are no shots. The password is the right one, shouted with all the breath by those thin and filthy ghosts.

What happened? The two informers, Captain Paoletti and Lieutenant Bertozzi of the Royal Army, have brought with them a cavalryman taken prisoner in Caporetto, who has escaped and has been sharing their hellish life for weeks. There is no room for everyone on the seaplane. The two informants matter, the other doesn't. Dogs barking through the fog is heard nearby. There is no time to exchange a glance. Everyone on board. The weight is too much and the Austrians are already in sight and are coming. Crouching on Bertozzi's lap, Casagrande gives the gas. The plane floats slowly, but does not take off, cannot. It is too heavy and the technical manual is clear: maximum takeoff weight 1350 kilograms, not a ton and a half. Shout from the ground, if the shore of the lagoon can be called land.

The flyer is slowly pulled towards the pilot's chest. Very slowly. The wooden hull bites the water that does not spring. It is cold that morning, very cold and there is a little wind. Just a drool that just frays the fog, but the years at the Academy of Livorno, Corso 1911, class leader Giuseppe Fioravanzo, served, like the hours and hours spent on the regatta jigs and on the old Flavio Gioia, training ship of a wind master , the frigate captain Leoniero Galleani.

The hydro runs against the wind, whistling the first shots and cutting water. It comes off, falls, flies. It's grotesque. A real duck looking desperately for the nest where they lay their eggs. The Isotta Fraschini engine from 150 horses, those of a motorcycle today, sings. On board, one of those present will remember, there is an Ave Maria, Gratia plena.

An hour later I am in Venice, the largest seaplane base in the world and the naval aviation base of the Regia Marina. The Gold Medal will be awarded, motu proprio, by the King to Lieutenant Eugenio Casagrande on 11 November 1918. Thirteen days for practice. It's another record.