The history of 6 aviators resurfaces in the memory Royal Air Force survived well 11 days in the icy Atlantic seas.

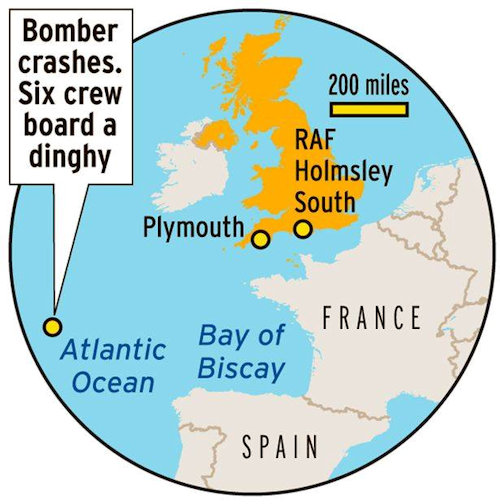

At the height of the Battle of the Atlantic a four-engine bomber Halifax, which took off on 27 September 43 from the Holmsley base, is on reconnaissance on the Bay of Biscay (off the coast of Brittany) when it intercepts and sinks a German U-boat, the U-221. At the controls of the British bomber is Eric Hartley who, irremediably hit in an engine, disengages after destroying the target and is forced to land 600 kilometers south-west of the coast of Ireland. Two crew members lost their lives during the action, the other six are now on a small yellow 'life-boat', without having been able to launch an SOS, with emergency rations sufficient for a few days and all around the freezing cold Atlantic waters that in October can reach 3-4 ° in temperature.

Freeze-dried milk, some biscuits, chocolate and chewing gum to keep you alive. The flight suits designed for bombers, 'Irvin Suit', consisting of a padded jacket and sheepskin trousers worn over the uniform to defend themselves from the cold, but not from high waves and rain. They are perpetually soaked, they try to fish - unsuccessfully - by using rudimentary nets made from the underpants of theair-gunner Ken Ladds and chewing gum as bait. They try to feed on 'jellyfish', the only thing they can catch, but they are disgusting.

They sew their shirts with copper wire to get a sail which, at 2 knots, slowly pushes them towards the continent. Together with the commander are the co-pilot, cpt. Roger Mead, the navigator, sgt. T. Bach, the borough engineer, sgt. George Robertson, the radio operator, sgt. A.Fox, and machine gunner Ken Ladds. Everyone suffers from the sea, the frost, some give the first signs of madness due to isolation and loss of hope. Hope that is deceived on the night of October 3, after six days adrift: when the light of Mars, which when it rises from the horizon in the starry nights of the Atlantic is orange and clear, is mistaken for the signal light of a vessel ; false alarm.

They sew their shirts with copper wire to get a sail which, at 2 knots, slowly pushes them towards the continent. Together with the commander are the co-pilot, cpt. Roger Mead, the navigator, sgt. T. Bach, the borough engineer, sgt. George Robertson, the radio operator, sgt. A.Fox, and machine gunner Ken Ladds. Everyone suffers from the sea, the frost, some give the first signs of madness due to isolation and loss of hope. Hope that is deceived on the night of October 3, after six days adrift: when the light of Mars, which when it rises from the horizon in the starry nights of the Atlantic is orange and clear, is mistaken for the signal light of a vessel ; false alarm.

Every night they watch the puffs of whales, a few meters from the inflatable boat. Every morning they empty the water brought on board by the waves with flight boots, to avoid sinking. A small ration of chocolate is prayed and distributed, until the end, until it loses hope, until October 8, when a ship is sighted. Three signal flares fired with a 'very' gun fill the sky, and the HMS Mahratta he rescues them, disembarking them in Plymouth on October 10.

This story, forgotten like many other war stories, resurfaced in memory after more than 70 years because relatives of pilot-commanded Eric Hartley decided to sell the Distinguished Flying Cross who earned that 27 September of the 1943 - "We have no children to pass it on to, we just need the memory to be proud of my father", the words of the sixty year old daughter before giving up the high recognition for the acts of value expressed last the conflict.