What characterizes the passage from the operations of the "first offensive rush" to the "First battle of the Isonzo" is the limitation of the objectives in depth - if not their definitive cancellation - and the use of the tactics of the fortress war; in other words, the stabilization of the front after the first clashes of May-June 1915.

The new orders of the Supreme Command impose slow and successive actions to the detriment of the strategic maneuver. That of parallels and approaches begins to be the preferential system of Italian tactics; carrying the guards forward, up to an assault distance, is to be preferred over the forward momentum. The overriding aim becomes to immediately strengthen a conquered position without attempting to pursue the retreating enemy troops.

By mid-June, what had been planned as a war of movement had to definitively turn into a tiring war of position with the same characteristics as the one going on on the western front, but with the worsening of a decidedly more difficult terrain. A practical example of this transformation in strategic and tactical doctrine, including the emergence of contrasts with the old methodologies, is without a doubt the battle of Quota 142, during the actions for the conquest of San Michele.

The Supreme Command had identified in the entrenched camp of Gorizia the main objective of the offensive that was about to be unleashed: the 2nd Army was entrusted with the task of directly attacking Mount Kuk 611 and the Oslavia-Podgora line, bulwarks of the entrenched camp; the 3rd Army to carry out an indirect support action with the conquest of the edge of the karst plateau between Monfalcone and Sagrado and the left bank of the Isonzo in correspondence with Mount San Michele.

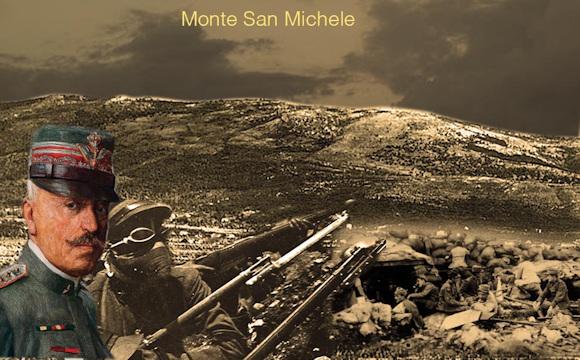

Overcoming the Isonzo between 23 and 24 June had been quite difficult due to the artillery fire and the firing of rifles against small boats and bridges; for Italian troops, however, the real obstacle remains San Michele, the strong point of the Austro-Hungarian defense system. This hill 250 meters high, irregular in shape and surrounded by five steep rocky spurs, due to its position (in the middle between Gorizia and the Karst) is the backbone of the Austrian defense system in the Lower Isonzo and its loss would mean opening the road to the Italians for the Gorizia stronghold and, from there, for Trieste.

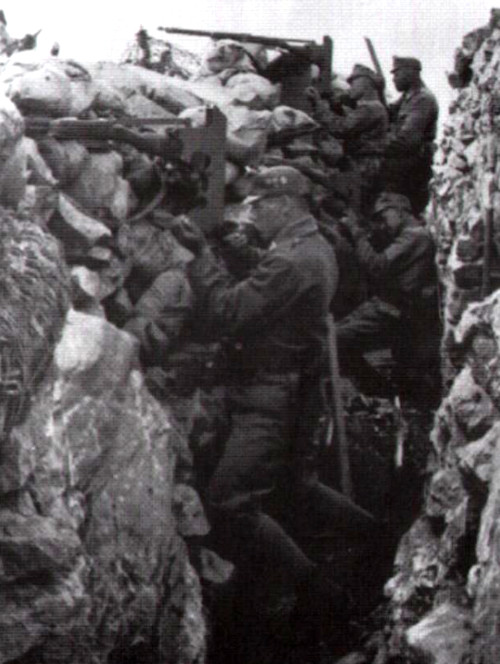

The battle for the conquest of San Michele therefore assumes a greater importance in this phase than the main action conducted by the 2nd Army. Due to the rocky terrain, the Austrians managed to dig deep trenches only up to the knee, then gently reinforcing the defensive line with dry stone and soil walls, while the frets were hidden with the fronds. Despite the approximation of the defensive works, the Austrians (photos)  they have a considerable advantage in that they have machine guns while the Italians do not.

they have a considerable advantage in that they have machine guns while the Italians do not.

Operations against Monte San Michele are entrusted to the 29th Division which includes the Pisa Brigade (30th and 142th Infantry Regiments) who are ordered to advance on Quota 06.00, among the five spurs of San Michele the one closest to the head of Sagrado bridge. At 142 in the morning of July 07.00st, while a violent storm out of season hit the Karst, the Italian soldiers crossed the wooded sides of Quota 08.00. Since the night before the use of the explosive pipes against the enemy barbed wire had had no effect, at 142 the artillery shooting resumes. The roar of cannons accompanies Italian soldiers marching in the pouring rain. Around 09.00 the sun shines again on the San Michele and in the sky you can see, once the haze has cleared, a rainbow. It seems auspicious. In an expanse of grass and rocks the soldiers rest for a few hours; you have to dry yourself and shake off the exhaustion. The good weather would allow the Italians to attack Quota 08.30 at XNUMX, just as planned. Around XNUMX the order to extend the artillery fire starts from the command. The difficulties of connection, however, are many and it is difficult to communicate to the infantrymen marching between Bosco Lancia and Bosco Cappuccio to be ready within half an hour.

Only at 12.00 is the order given to prepare for the assault: the soldiers form a line resting one knee on the ground while the officers remain standing with their sabers unsheathed. The formation is a perfect example of what General Cadorna codified in his tactical instructions for the infantry. You have to attack the steep slope of Quota 142 in the open, with 35 kg of equipment on your shoulders and under the cross fire of machine guns that you can't even see. Not to mention that the Austrian artillery located in the Savogna plain is ready to hit the infantrymen on the sides at the time of the attack.

When the signal comes, the scream "Savoy!" burst into deadly silence and the Italian infantry sprang like a spring to the assault. The officers wield the saber with their right hand and with their left they hold the sheath to avoid tripping while the soldiers struggle to move under the weight of the backpacks. The greyish mass immediately becomes a privileged target for the Austrians who, after a few seconds, open fire, mowing down the officers while the soldiers, on all fours, seek desperate shelter. The first Italian attack on San Michele ends even before it begins.

In the afternoon a second attack is stopped by the Italian artillery fire which, with the lift too low, ends up hitting the friendly lines. The operations are temporarily interrupted due to a new violent burst of rain, thus giving the Pisa Brigade time to regroup. After the storm the Italians attack the hill in small groups and the enemy machine-gunners no longer have the ease of previous shooting.

When the infantrymen with black-green insignia manage to leap over the dry stone walls it is massacre of enemies. In the melee the Italian officer armed with a saber is superior to the Austrian, just as the Italian infantryman is better trained in the use of the bayonet than his enemy. The finely engraved blades of the sabers and the roughly burnished blades of the bayonets are stained with blood and the ground strewn with Bosnian corpses in Habsburg uniform.

The battle of San Michele had just begun, yet at altitude 142 it seemed evident that, on certain occasions, the principles contained in "frontal attack and tactical training" - albeit "amended on the field" by platoon commanders and company with the last victorious assault on Altitude 142 - remained valid.

At Quota 142 one of the first episodes had taken place - and there will be many others during the "First Battle of the Isonzo" - of the difficult coexistence between a rigidly offensive tactical mentality and a strategy that was now changing its skin to assume the typical traits of the obsidional art. An unhappy synthesis which, in essence, represents the litmus test of those defects - still in a nutshell - which would later have constituted a serious limitation to the management of the Italian war until the turning point of 1917.

Philip Del Monte

Essential bibliography:

• The Italian Army in the Great War (Operations in 1915) T. II, Rome, 1929

• The Great War, Emilio Faldella, Milan, 1965

• Frontal attack and tactical training, Rome, 1915

Photo: Salvatore Cuda (opening image) / web