Some recent articles in the prestigious US newspaper New York Times have explained to the public across the Atlantic (and beyond) some of the excellent results achieved by the Navy during the "Mare Nostrum" operation. The American press noted with admiration that, beyond the fundamental safeguarding of human lives, this was an extremely effective military operation in identifying and targeting the trafficking networks that lurk behind the trafficking of human beings. In reality, the Navy's ability to combine operational effectiveness with the protection of humanitarian law has distant roots and many precedents, known and less known.

In the same days of the 1940 in which, in full Battle of the Atlantic, the commander Todaro and the men of the submarine Cappellini were doing their utmost to rescue the shipwrecked people of the adversary merchant Kabalo, another humanitarian operation, certainly less known, but also significant, was underway in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Il war diary of the Marine Command in Stampalia, in the Aegean, in fact, reports that on 5 October, at the end of an antisom hunt, the MAS 523 and 531 of thea squadrons had returned escorting a mysterious, small steamer, overloaded and smelly, intercepted in our territorial waters. It was the Pentcho, a battered river boat with on board, in indescribable conditions, 509 people among which 142 women and 9 children, all refugees from Israel of various nationalities.

Il war diary of the Marine Command in Stampalia, in the Aegean, in fact, reports that on 5 October, at the end of an antisom hunt, the MAS 523 and 531 of thea squadrons had returned escorting a mysterious, small steamer, overloaded and smelly, intercepted in our territorial waters. It was the Pentcho, a battered river boat with on board, in indescribable conditions, 509 people among which 142 women and 9 children, all refugees from Israel of various nationalities.

The ship had left Bratislava, Slovakia, sailing in shocking conditions for months to finally enter the Caso Channel, where it was sighted by the Italian MAS. After the stop in Stampalia, during which the cart was stocked with fruit and vegetables, also providing the sanitary and sanitary needs of all, the refugees set sail again in an attempt to travel the last route to Palestine, forcing the English blockade . Along the route the Pentcho but he was hit by a series of failures, brought to the carving on the uninhabited rock of Kamila Nisi and abandoned by the crew.

Sighted by the efficient British reconnaissance, the refugees remained abandoned to themselves. The British did not consider it useful to intervene, being already engaged in the difficult trailer of the cruiser Liverpool, badly damaged in Suda, shortly before, by an Italian torpedo aircraft.

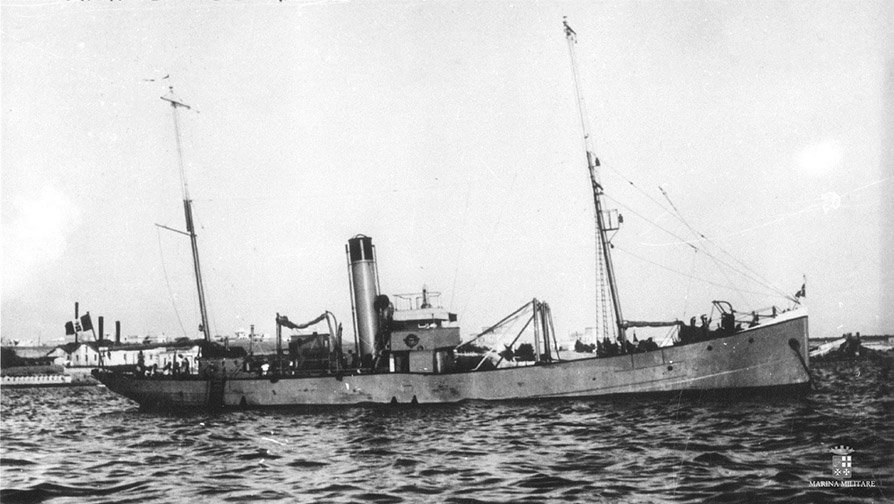

So it was the turn of the small transport of the Royal Navy Camogli (photo below) under the command of the head of 1a class coachman Carlo Orlandi, who recovered the survivors, supplying them and transporting them, one group at a time, to Rhodes between 18 and 26 October 1940. According to the immutable and fundamental laws of the sea, precedence was given to women and children. Through complicated diplomatic and humanitarian affairs, Jewish refugees were finally transferred to Italy in the 1942, interned in the field of Ferramonti in Calabria. Everyone was saved, less one family, remained in Rhodes near a distant relative and fallen victim of the Germans in the 1944.

So it was the turn of the small transport of the Royal Navy Camogli (photo below) under the command of the head of 1a class coachman Carlo Orlandi, who recovered the survivors, supplying them and transporting them, one group at a time, to Rhodes between 18 and 26 October 1940. According to the immutable and fundamental laws of the sea, precedence was given to women and children. Through complicated diplomatic and humanitarian affairs, Jewish refugees were finally transferred to Italy in the 1942, interned in the field of Ferramonti in Calabria. Everyone was saved, less one family, remained in Rhodes near a distant relative and fallen victim of the Germans in the 1944.

To the acts ofhistorical office is the request for information at the time made to the Navy regarding the possibility of adding the name of Commander Orlandi in the famous list of the "Righteous" drawn up by Yad Vashem of Jerusalem.

This story of smugglers, then tracked down and punished by the Italian authorities, and of sorrowful humanity, dates back to World War II: today things do not seem much changed. Perhaps the nature of men never changes, certainly that of the Navy has never changed.