The Japanese air force was not an independent armed force, both the Army and the Navy had their own air force and the two were often in conflict with each other, both in terms of operational strategy and priority in the supply of vehicles and materials.

The real backbone of the Japanese air forces was the aviation embarked on the large aircraft carriers, in addition to the bombing, torpedoing and reconnaissance wings based on land. The latter are responsible, for example, for operations such as the sinking of English ships Repulse e Prince of Wales and the aircraft carrier Hermes. With the progressive sinking of the aircraft carriers by the United States and the decimation carried out on their embarked groups, naval aviation played an increasingly marginal role, going from an offensive weapon to a simple close escort (in the best of cases) or a tank of means and increasingly inexperienced pilots due to the widespread use of kamikazes towards the end of the war.

In 1910, Japan acquired its first airplane, a type similar to the one designed and flown by the French aviator Henri Farman (1874-1958). In 1912, the Royal Navy had established its own embarked air force called the “Royal Naval Air Service”. The Japanese Navy had observed technical developments in other countries, recognizing that the aircraft had considerable potential for use.

The following year, in 1913 an Imperial Navy transport ship, the Wakamiya it was transformed into a seaplane support ship, and a series of aircraft was purchased.

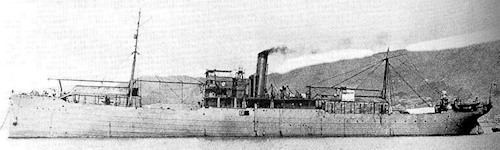

Il Wakamiya (following photo) was originally the English cargo ship Lethington, built by the Duncan shipyard of Port Glasgow for WR Rea Shipping of Belfast, and launched on 21 September 1900. Chartered by the Russians during the Russo-Japanese War, on 14 February 1905 while traveling from Hong Kong to Vladivostok she was captured by a Japanese torpedo boat off the Oki Islands (Okinoshima). After compensation to the shipping company, she officially entered service in the Japanese Merchant Navy in September 1905 under the name Wakamiya Maru.

In 1913 the unit was purchased by the Imperial Navy and converted into a seaplane carrier and renamed simply Wakamiya.

In April 1920, it underwent further modifications and was renamed to Wakamiya-kan, and in June of the same year it made the first Japanese takeoff from a carrier. Further take-off and landing tests were carried out in 1924. In 1925 it was placed in reserve at the Sasebo Naval District. She was deregistered in 1926 and sold for demolition in 1932.

On August 23, 1914, Japan declared war on Germany. The Japanese laid siege to the German colony of Kiaochow and its administrative capital Tsingtao on the Shandong Peninsula. During the siege, starting in September, Maurice Farman seaplanes, a two-seater reconnaissance and bombing biplane (two effective and two reserve) based on the Wakamiya they conducted reconnaissance and bombing of German positions. September 30th Wakamiya it was damaged by a mine, but the landed seaplanes continued their raids until the German surrender on 7 November 1914.

In military history the Wakamiya it was the first ship in the world to launch air raids. By the end of the siege the Japanese air force had conducted 50 raids and dropped 200 bombs, although damage to German defenses was negligible.

The Japanese Navy had closely followed the naval aviation progress of the three Allied Powers during World War I, and concluded that Britain had made the greatest progress in that area. In September 1921, with the aim of helping the Imperial Navy develop its naval and air forces, the British sent the “Sempill” mission to Japan led by Captain Sempill (1893-1965), an air and naval technician. The mission consisted of a group of 29 instructors, who remained in Japan for 18 months, providing the Japanese Navy with quality support in aviation, training, and technology.

The Japanese Navy had closely followed the naval aviation progress of the three Allied Powers during World War I, and concluded that Britain had made the greatest progress in that area. In September 1921, with the aim of helping the Imperial Navy develop its naval and air forces, the British sent the “Sempill” mission to Japan led by Captain Sempill (1893-1965), an air and naval technician. The mission consisted of a group of 29 instructors, who remained in Japan for 18 months, providing the Japanese Navy with quality support in aviation, training, and technology.

With new Gloster aircraft Sparrowhawk, (photo - single-seat biplane fighter designed by the British Gloster Aircraft Company and produced in the following years initially in the Gloster factories and subsequently in Japan from the first technical naval aeronautics arsenal of Yokosuka) the Japanese learned various techniques on flight control, torpedoing and bombing .

Lo Sparrowhawk It entered service in 1921 and was used to train pilots and personnel on take-off and landing operations, remaining in service as a trainer at naval bases until its withdrawal in 1928.

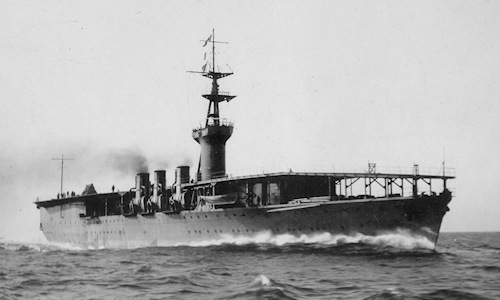

The mission also brought the plans of the recent British aircraft carriersArgus andHermes, which influenced the final stages of the development ofHosho (photo) which became the first aircraft carrier designed and built entirely in Japan.

With the debut of the first Japanese aircraft carrier in 1920, the naval air force initially had reconnaissance and attack tasks but - like the US Navy - the Imperial Navy had difficulty integrating aircraft into naval tactics.

During the 20s, a second foreign delegation for army training was also in Japan: the German one. Like the German Air Force in World War I, the Japanese Army Air Force was closely tied to it and its movements.

Until the early 1930s, the two Japanese air transport services, Army and Navy, were primarily equipped with obsolete foreign aircraft either imported or built under license. In this period, Japanese designers began to produce various aircraft at home that were more suitable for their operational needs.

Due to the distances and general secrecy of the Japanese government and the manufacturing company, this important change was not received in the West and not fully appreciated by the Americans.

Even in 1941 at the beginning of the Pacific War, it was widely believed in US military circles that Japan had at most a few hundred aircraft, mostly copies of older British, German, Italian and American ones. There seemed to be no reason to suppose that the Japanese had very well-trained aircraft and pilots, in particular. They compared the Japanese air force to the Polish air force of 1939.

Even in 1941 at the beginning of the Pacific War, it was widely believed in US military circles that Japan had at most a few hundred aircraft, mostly copies of older British, German, Italian and American ones. There seemed to be no reason to suppose that the Japanese had very well-trained aircraft and pilots, in particular. They compared the Japanese air force to the Polish air force of 1939.

In 1937 from the start of hostilities, until 1941, the Imperial Navy's aviation played a key role in military operations on the Chinese mainland, then in 1941 its forces were diverted to fight the Americans.

Despite the strong rivalry between the military branches, in the autumn of 1937 the army general in command of the Chinese theater of war, Iwane Matsui (1878-1948), admitted the superiority of Navy aircraft. Aircraft that attacked Chinese positions in and around Shanghai, naval bombers such as the G3M and G4M (photo) were used to bomb Chinese cities. Japanese fighter planes, especially the Mitsubishi Zero, having gained tactical air superiority, mastered it in the sky.

Unlike other naval aviation, Navy aircraft were responsible for the bombing raids that were carried out largely against large Chinese cities, such as Shanghai, Wuhan, and Chongqing, with approximately from February 1938 to August 1943, over five thousand raids.

The bombing of Nanjing and Canton (photo), which began on the 22nd and continued on the 23rd of September 1937, provoked international protests which ended with a resolution of the consultative committee of the League of Nations against Japan.

The bombing of Nanjing and Canton (photo), which began on the 22nd and continued on the 23rd of September 1937, provoked international protests which ended with a resolution of the consultative committee of the League of Nations against Japan.

The Imperial Navy was assigned a considerable amount of tasks and, with these, the resources (planes, factories, personnel, depots, etc.) necessary to carry them out.

At the beginning of the Pacific War, the Imperial Navy consisted of five fleets. At the start of hostilities the Japanese had ten aircraft carriers, six of the fleet, three smaller carriers and one under construction.

On December 10, shore-based Navy bombers belonging to the 11th Group sank the ships Prince of Wales e Repulse. Raids were also carried out on the Philippines and on Darwin in northern Australia.

From 16 December 1941 to 20 March 1945 the naval aviation had 14.242 deaths of which 1.579 were officers.

In 1941 the Imperial Navy had approximately 3.100 aircraft and another 370 for training and pilot training. 11.830 front-line aircraft, including:

In 1941 the Imperial Navy had approximately 3.100 aircraft and another 370 for training and pilot training. 11.830 front-line aircraft, including:

- 660 fighters, mostly Mitsubishi Zero,

- 330 based on aircraft carriers,

- 240 land-based bombers,

- 520 seaplanes (including fighter and reconnaissance).

The best pilots were the carrier-based groups named “kokutai”, and later called “Sentai koku”, whose composition varied from 80 to 90 aircraft.

The ships of the fleet had three types of aircraft: fighters, torpedo bombers and dive bombers. Smaller aircraft carriers had only two: fighters and dive bombers.

The Imperial Navy maintained a system based on named air fleets “Koku Kantai and Kantai Homen” comprising mostly twin-engine aircraft, bombers and seaplanes, the command was the 11tha Air Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Nihizo Tsukuhuru. Each air fleet consisted of one or more flotillas under the command of naval officers, each with two or more groups of aircraft. Each group consisted of several “hikotai” (squadron) composed of 9, 12, or 16 aircraft. Everything is fine “hikotai” it was commanded by a lieutenant (JG), while most of the pilots were non-commissioned officers. There were usually four sections in each “hikotai”, and each section (“shotai”) was made up of three or four planes.

At the beginning of the Pacific War, there were over 90 groups each with a name or number. Groups with a name were usually tied to a particular Navy air command, or a Navy base. While groups with a number usually received it when they left Japan.

At the beginning of the Pacific War, there were over 90 groups each with a name or number. Groups with a name were usually tied to a particular Navy air command, or a Navy base. While groups with a number usually received it when they left Japan.

This situation of use of the air forces divided between the army and the navy led to the Japanese air collapse. A high-level meeting to resolve these discrepancies and to make the most of the activities that each service had, would have been a reasonable response to the situation. But it never happened.

When the Japanese empire teetered toward total collapse a couple of years later, the preponderance of tasks and activities still fell to the Navy's air force.

During the final months of the Pacific War, the surviving units were mostly isolated and helpless, their planes parked close to the airstrips, with no prospect of supplies of aviation gasoline, spare parts and ammunition, at the mercy of the efficient American air force.

Photo: US Navy / web