La battle of the Nile, known in France as the battle of Abukir (located north-east of Alexandria), which took place on August 1798, XNUMX, is the "daughter" of Horatio Nelson's great military prowess, the unpreparedness of the French navy and British naval dominance.

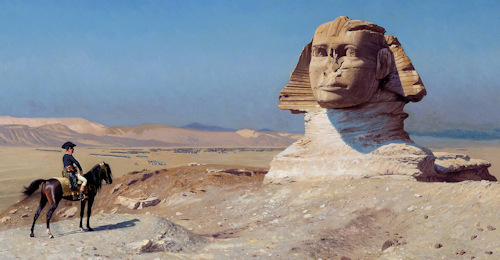

Napoleon Bonaparte, who came out of the great triumph of the Campaign of Italy in 1798, was to be considered the rising star of the new revolutionary army, and for this reason the Directory supported his courageous plan which had as its objective that of conquering Egypt. An expedition to the East would have seriously threatened British trade with the Indies.

France had not given up on her great dreams about India, and General Bonaparte not only revived them now, but he also tried to turn them into reality. Napoleon, in fact, among the many innovations brought the breakdown of geostrategic balances, and the Mediterranean Sea will play a decisive role in this.

The Mediterranean is a very complex system for geography, climate, culture and history, a set of various realities linked by a common destiny. During the period under consideration, this sea was large enough to accommodate interests and actions of disparate origin, and at the same time small enough for all events to end up influencing each other, adding up and producing universal consequences. All this, however, makes us understand the strategic role that the Mediterranean has.

In the period that I draw the sea was (and still is today) basically a way of communication, a space through which people and goods, raw materials or manufactured goods, could move in all directions, but favoring, for obvious reasons of convenience , certain routes, because they are shorter or only because they are easier to navigate. All this, together with the ports of departure and destination and the dislocated bases, represented a dense network of relationships and interests of particular value. The bases were emporiums, warehouses, access to continental areas, but at the same time they also had to serve as reference points for merchant ships and military ships that were forced to sail to areas far from their nation. This latter requirement, "of a more typically strategic-military nature, was the cause of many of the disputes that occurred in the Mediterranean"1. Exactly as was the case with Abukir.

In the period that I draw the sea was (and still is today) basically a way of communication, a space through which people and goods, raw materials or manufactured goods, could move in all directions, but favoring, for obvious reasons of convenience , certain routes, because they are shorter or only because they are easier to navigate. All this, together with the ports of departure and destination and the dislocated bases, represented a dense network of relationships and interests of particular value. The bases were emporiums, warehouses, access to continental areas, but at the same time they also had to serve as reference points for merchant ships and military ships that were forced to sail to areas far from their nation. This latter requirement, "of a more typically strategic-military nature, was the cause of many of the disputes that occurred in the Mediterranean"1. Exactly as was the case with Abukir.

In absolute secrecy - only the government and Bonaparte were aware of the real target by sea - the Armée d'Orient sailed from the city of Toulon on 19 May 1798. Other divisions embarked in the cities of Marseille would then have reached it, Genoa and Civitavecchia. It was the largest fleet ever seen in the Mediterranean. In total there were 280 ships, including 13 scheduled, with a number of cannons between 74 and 118 (the one with 118 cannons, the largest, was the flagship L'Orient, commanded by Vice-Admiral Francois Brueys). Bonaparte had assembled 38000 soldiers, 13000 among sailors and marines and 3000 sailors of commercial ships.

The English spies who were based in Toulon understood that a major operation was being prepared in the Arab countries, but they were unable to report to London what the real target of the French was. So to the rear admiral Horation Nelson was given an order to "blind": try to intercept the French fleet. The information collected first in Naples and chased by some crossed ships on the route convinced the admiral that the real target of the French was Egypt.

Napoleon's great army was very fortunate to be able to cross the Mediterranean without being attacked by Nelson, who was on his trail with 13 liners. The evening before Bonaparte sailed, a storm had dispersed Nelson's fleet around Sardinia, and on the night of June 22 the two fleets crossed in the fog, passing just 20 miles from each other near Crete.

In doing so, Napoleon arrived in Alexandria without too many problems on the first of July and the following days he was already marching with the army to Cairo. Now we had to figure out where to repair the naval team. Admiral Brueys decided for Abukir, a bay not very deep and protected by a sandy promontory where there was a fort.

It was on the afternoon of August XNUMXst that Nelson's lookouts sighted the French. Although the French team was anchored in a fortified port, surrounded by shallows and slums that limited the space for an offensive maneuver, "the French admiral Brueys had left too many spaces between his ships, thus allowing the most maneuverable British vessels to infiltrate in a row to attack enemy ships at close range thanks to the power of the new artillery "2. This was the tactic preferred by the British, who aimed at the opposing bridges and crews, while the French gunners were trained to hit the maneuvers of enemy ships, with the aim of immobilizing them to make them harmless, without continuing in their destruction. Admiral Nelson had 13 vessels of 74 cannons and one of 50, with a total of 938 cannons, the French instead of more than a thousand. But the French team was taken by surprise.

Nelson decided to take advantage of the situation without allowing time for the French team to implement countermeasures. So in command of the British formation began to advance concentrating immediately on a few opposing units in order to destroy them before the others could intervene.

Nelson's tactic was strategically decisive. The Englishman made the attack on the column against an opposing fleet, breaking the traditional doctrines that were based on line fighting in a row. The French vanguard was positioned far from the fort, making it difficult for howitzers and cannons to hit British ships from the ground. Among other things, the row of ships of Admiral Brueys had positioned itself far from the coast, and in this way gave the opponent a navigable channel. So Admiral Nelson wasted no time and had five of his ships threaded to seize the opponent between two fires.

In the late afternoon, the British units engaged the seven French avant-garde ships with hard and precise stringing fire which, in the end, were reduced to wretched boats. Admiral Brueys was killed in the course of the fight and L'Orient jumped into the air (opening and bottom image).

Taking stock of the battle, it turned out that apart from two liners and two frigates, all French units had been sunk, captured or run aground. The survivors left Abukir bay under the command of Rear Admiral Villeneuve.

The defeat for the French resulted in the isolation of the Armée d'Orient, the interruption of the connections between Bonaparte and Paris and was, in particular, the cause of the failure of the expedition to Egypt.

The route with the Indies remained exclusive to the British who with the victory in Abukir confirmed that they were masters of the seas.

Later, thanks to naval and maritime power, the United Kingdom emerged from the Napoleonic wars as the largest of the powers, the richest and most important. In fact it had no rivals.

It had a new industrial system and dominated maritime trade, through which, with the protection of the most impressive military navy in the world, it could export the products resulting from its technical and organizational superiority. In fact, he always had the strength to influence the Mediterranean Sea in a determined way.

It can be said, without too many problems, that the British managed to maintain this position of strength at least until the Second World War, when they were then replaced by the United States of America as a hegemonic power. Even in that case, as in the Napoleonic wars, the defense of the Mediterranean from the Axis powers was of vital importance. As well as avoiding, at all costs, that Egypt could be conquered by the Axis. In fact, a victory in Egypt would have paved the way for the entire Middle East (rich in oil reserves). Thereafter there would be a high risk of reaching - as in the past - to India.

This demonstrates how in history, characters, contexts, alliances and businesses (before there were spices, now oil) can vary. But nations, objectives and economic-strategic interests in the end remain and will always remain. Just as the maintenance of certain geostrategic areas (such as the Mediterranean) is fundamental for controlling others.

1 L. Donolo, The Mediterranean in the Age of Revolutions. 1789-1849, Pisa University Press, Pisa, 2012, p. 8.

2 A. Savoretti, The great admirals of the sailing age, Odoya, Bologna, 2018, p. 264.

Images: web