The history of Kosovo is extremely extensive in time and full of numerous crucial events. This article will examine, however briefly, the main historical passages up to the conclusion of the Great Battles of Kosovo.

The geographical area of Kosovo was part of the Macedonian Empire in ancient times and later of the Roman Empire. With the weakening of the Byzantine Empire, while retaining the proto-Albanian social and cultural structure, it was colonized by the Slavs and became part of the Bulgarian Empire and then became part of the medieval kingdom of Serbia and the Serbian Empire. With the fragmentation of the latter, and following the defeat in the Battle of the Plain of Merli in 1389 (opening image), Kosovo came under Ottoman rule for more than five centuries.

From Ancient History to the Middle Ages

The area of Kosovo has been inhabited without interruption since the Neolithic, a period in which human communities belonging to the Starčevo culture were active1 and, which century later, to the Vinča culture2.

In the XNUMXth century BC, the area of Kosovo was located at the eastern end of Illyria3, on the border with Thrace4. The first tribes of which we have information are the tribal Thracians, concentrated in present-day Wallachia, whose reach however extended up to present-day Kosovo until the XNUMXrd century BC, and the Dardanians, who followed them between the XNUMXrd and XNUMXst centuries B.C

In the following centuries, the area of Kosovo, known as part of Dardania and characterized in ancient times by a very low level of urbanization and penetration of classical civilization, was occupied by Alexander the Great in the XNUMXth century BC

In the following centuries, the area of Kosovo, known as part of Dardania and characterized in ancient times by a very low level of urbanization and penetration of classical civilization, was occupied by Alexander the Great in the XNUMXth century BC

The ancient Balkan region included approximately present-day Kosovo and neighboring areas of Albania, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Montenegro. It was inhabited by the Illyrian tribe of Dardanians, from whom it took its name.

It was conquered by Rome in 160 BC and subsequently incorporated into the Roman province of Illyricum in 59 BC. It then became part of Moesia5 in the year 87 AD

Starting from the XNUMXth century, the area of Kosovo, now largely Romanised, was integrated into the Province of Dardania of the Byzantine Empire, which was however constantly focused on the wars in the East against the Persians and the Arabs6.

As Byzantium's authority and control over the Balkan hinterland weakened, the region remained exposed to various barbarian incursions, culminating in the great Slavic migrations of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries from Eastern Europe7.

The subsequent political and demographic history of Kosovo is not known with absolute certainty until the XNUMXth century.

The region was absorbed into the first Bulgarian Empire around 850, with the definitive consolidation of Christianity and Slavic-Byzantine culture. It was reconquered by the Byzantines in 1018 and became part of the new Subject of Bulgaria8.

As a focal point for Slavic resistance to the power of Constantinople on the peninsula, the region often changed domination, between Serbs and Bulgarians on the one hand and Romans from Byzantium on the other, until the arrival of the Serbian prince Stefan Nemanja9 (image), who secured control of it at the end of the XNUMXth century.

As a focal point for Slavic resistance to the power of Constantinople on the peninsula, the region often changed domination, between Serbs and Bulgarians on the one hand and Romans from Byzantium on the other, until the arrival of the Serbian prince Stefan Nemanja9 (image), who secured control of it at the end of the XNUMXth century.

Serbia at that time was not yet a unified kingdom: there existed a large number of small Serbian principalities to the north and west of Kosovo, the most powerful of which were Rascia (corresponding to the central area of modern Serbia) and Doclea (i.e. the current area of Montenegro and northern Albania). These principalities were often at war with the Empire.

In 1180, the Serbian lord Stephen Nemanja took control of Doclea and part of Kosovo. His successor, Stephen Prvovenčani, assumed control of the rest of the area by 1216, thus creating a state that incorporated most of the area consisting of today's regions of Serbia and Montenegro10.

The ethnic composition of the population of Kosovo during this period is still a subject of controversy between Serbian and Albanian historians today.

The Serbian ethnic group seems to have been the culturally and linguistically dominant population, and probably also represented the demographic majority: this is proven by the foundation charter of Dečani, the oldest of the very rare existing documents, which however dates back to 1330, about a century after beginning of Serbian domination.

In the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, Kosovo became the political and spiritual center of the Serbian kingdom. At the end of the XNUMXth century, the seat of the Serbian archbishopric was moved to Peć, while the rulers moved between Pristina, Prizren and Skopje.

Hundreds of churches, monasteries and feudal strongholds were built in the same period. Kosovo was, in those years, economically important, as was the capital of modern Kosovo, Pristina, which was an important commercial hub on the roads leading to the ports of the Adriatic Sea. Likewise, mining activity also had great importance.

The peak of Serbian power in the region was reached in 1346 with the formation of the Serbian Empire and the coronation of Stephen Dušan as Tsar of the Serbs, Vlakhs, Greeks and Albanians. However, upon his death in 1355, the Serbian Empire fragmented into a series of feudal principalities. Kosovo became the hereditary land of the Mrnjavčević and Branković families.

The peak of Serbian power in the region was reached in 1346 with the formation of the Serbian Empire and the coronation of Stephen Dušan as Tsar of the Serbs, Vlakhs, Greeks and Albanians. However, upon his death in 1355, the Serbian Empire fragmented into a series of feudal principalities. Kosovo became the hereditary land of the Mrnjavčević and Branković families.

In the late XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, some areas of Kosovo, reaching even Pristina itself, were part of the principality of Dukagjini, later incorporated into the anti-Ottoman federation composed of all the Albanian principalities, the League of Alexios11.

This occurred in conjunction with the first Ottoman expansion in the Balkans: the Ottoman Empire seized the opportunity offered by Greek and Serbian weakness and invaded those territories12.

The Great Battles of Kosovo

One of the best known clashes in the history of the Balkans is certainly the Battle of Piana dei Merli. The conflict occurred on the field of the same name on 15 June 1389, when the knez13 of Serbia, Lazar Hrebeljanović, gathered a coalition of Christian soldiers, composed of Serbs but also Bosnians and Magyars, and a contingent of Saxon mercenaries14.

The Ottoman sultan Murad I also assembled a coalition of soldiers and volunteers from the neighboring countries of Rumelia and Anatolia. Providing exact figures is certainly not easy, but some accounts provided by historians suggest that the Christian army was far inferior to the Ottoman one. The total of the two armies is believed to have been less than 100.000. The Serbian army was routed and Lazar was massacred. Murad I also perished in that legendary clash15.

Following this, Lazar's son and other Serbian principalities accepted a form of nominal vassalage to the Ottoman sultan, to whom Lazar's daughter was offered in marriage to seal the peace. Already in 1459, however, the Turks conquered the new Serbian capital, Smederevo, leaving Belgrade and Vojvodina under Magyar power until the mid-XNUMXth century16.

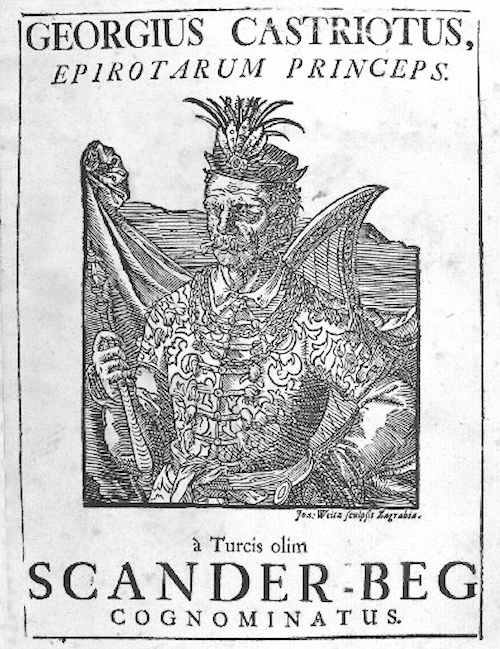

The second and most important battle of Kosovo was fought by Giorgio Castriota Scanderbeg, who liberated Kosovo and Albania from the invading Ottomans at the Battle of Mokra on 10 October 1445. The Ottoman army, composed of 15.000 knights and led by Firuz Pasha, he had orders to destroy Scanderbeg and the Albanians. Castriota decided to wait for the offensive at the Prizren gorges on 10 October 1445 and, thanks to his strategic skills, he emerged victorious.

The second and most important battle of Kosovo was fought by Giorgio Castriota Scanderbeg, who liberated Kosovo and Albania from the invading Ottomans at the Battle of Mokra on 10 October 1445. The Ottoman army, composed of 15.000 knights and led by Firuz Pasha, he had orders to destroy Scanderbeg and the Albanians. Castriota decided to wait for the offensive at the Prizren gorges on 10 October 1445 and, thanks to his strategic skills, he emerged victorious.

Murad II had sent an army of 25.000 men, including 15.000 cavalry, under the command of Ali Pasha, his most illustrious general. The latter entered Albania from the north-eastern part of Kosovo. One of the first measures of the Albanian prince was to create a host of military spies distributed in all communication nodes between Adrianople and Albania. Thanks to this intuition, he remained aware of every movement and always knew precisely the number of enemies headed towards him. He immediately recruited 15.000 men, including 7.000 cavalry, and camped in Torvioll, near modern-day Tirana, in a small valley (a rectangle of land measuring approximately seven by three miles), surrounded by mountains, which were in turn covered with woods . In these woods he hid half of his cavalry, leaving only a small part of the infantry on the field and then moving Ali Pasha towards him, luring him with maneuvers into the small field where he had decided to do battle.

He arrived here on 28 June 1444 and that day he definitively deployed all his units. On the right the mountaineers of Dukagjini, on the left the Bulgarians of Mokrena and in the center the guard of Scanderbeg. There was also a rear reserve of over 3.000 men. Another 3.000 under the direct command of Hamza Castriota were hidden in the woods around the camp.

The enemy's superiority was therefore canceled out by the narrowness of the field: the Turks were unable to surround the Christian army in any way.

The Turks had 8.000 dead, 2.000 prisoners, 24 flags lost and their entire camp ended up in the hands of the victors. Murad II, fearful of the stratagems used by the Christians, asked the Hungarians for peace and obtained it for ten years.

On 12 July 1444 it was signed in Szegedin, with the conditions for the sultan to return occupied Serbia to Đurađ Branković, together with his children taken as pledge, and the commitment not to invade Scanderbeg's lands.

The ten-year peace, however, lasted only six weeks. Ladislaus, king of Poland and Hungary, decided to break the treaty and attack, taking advantage of the sultan's absence. The King then entered Bulgaria with an army made up of 14.000 Poles, Hungarians and Romanians. He set up camp in Varna and waited for the Crusader allies to arrive. Scanderbeg in fact committed himself to reaching his Polish ally and set off on 15 October, after having gathered another 15.000 men. He would have reached it if the sovereign Brankoviç had not found the pass blocked, who, having not broken the peace with the sultan, certainly did not want to antagonize the latter.

The ten-year peace, however, lasted only six weeks. Ladislaus, king of Poland and Hungary, decided to break the treaty and attack, taking advantage of the sultan's absence. The King then entered Bulgaria with an army made up of 14.000 Poles, Hungarians and Romanians. He set up camp in Varna and waited for the Crusader allies to arrive. Scanderbeg in fact committed himself to reaching his Polish ally and set off on 15 October, after having gathered another 15.000 men. He would have reached it if the sovereign Brankoviç had not found the pass blocked, who, having not broken the peace with the sultan, certainly did not want to antagonize the latter.

Scanderbeg thus lost more than three weeks in negotiations and, exhausted and restless, gave orders to his men to pass anyway, despite the Serbs' disagreement. He had already reached Serbia when, however, he learned of Ladislaus' defeat and death from Hungarians and Polish fugitives.

Murad II therefore had to continue the fight in the Balkans and deal with Scanderbeg. The sultan sent Hajredin Bey with peace proposals, which were however rejected. To keep the situation under control, an army of 9.000 knights led by Firuz Pasha was sent. Their task was not to provoke the Albanians, but they should have stalled and set up an ambush when the latter crossed the border.

Scanderbeg faced the Ottoman army in the Mokrena plain, inhabited by Bulgarians, but under his direct rule, with only his guard. He confronted him on 10 October 1445 in a wood, near Prizren, where he had pushed him with numerous, rapid and decisive guerrilla actions. The Ottoman horsemen were impeded by the trees and were annihilated by the Albanians on foot who appeared from everywhere. Leaving 1.500 dead and 1.000 prisoners, Firuz Pasha returned defeated to Adrianople.

Giorgio Castriota Scanderbeg was the only leader, still considered an Albanian national hero, to free Kosovo from the Ottoman invasion.

Kosovo maintained its independence together with Albania until Scanderbeg's death in 1468. Afterwards, the region was again conquered by the Turks again.

The third battle was fought over two days in October 1448, between the Hungarian force commanded by John Hunyadi and the Ottoman army led by Murad II. Significantly larger than the first battle, with both armies double the size of the 1389 conflict, the final result was the same, however, and the Hungarian army was defeated in battle.

When the Albanian troops of Scanderbeg, who was unable to personally take part in the battle, moved to join the Hungarian ones, they fell into an ambush set for them by the Serbian Đurađ Branković, officially allied with the Ottomans, and never reached the field of battle.

Although the defeat in battle was a step backwards for those resisting the Ottoman invasion of Europe, it was not a definitive blow, so much so that Hunyadi was able to maintain active Hungarian resistance against the Ottomans throughout his entire life .

Read "Kosovo (second part): the Ottoman Empire"

Read: "Kosovo (third part): the Balkan Wars (1912-1913)"

Read: "Kosovo (fourth part): the First World War and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia"

Read: "Kosovo (fifth part): Socialist Yugoslavia and the Pristina Spring"

Read: "Kosovo (sixth part): towards conflict"

1 Neolithic archaeological culture from Eastern Europe and the Balkans, dating back to between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth millennium BC. The population who developed the Starčevo culture is considered the founder of Belgrade, the current capital of Serbia, in an era in which, however, no there were still Slavic peoples in the Balkans.

2 Prehistoric culture that developed in the Balkan peninsula between the XNUMXth and XNUMXrd millennium BC

3 Region corresponding to the western part of the Balkan peninsula, i.e. the south-eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea, inhabited by the Illyrians, an ancient Indo-European speaking population.

4 Region located in the extreme south-eastern tip of the Balkan peninsula. Compared to today's borders, it includes northeastern Greece, southern Bulgaria and European Turkey.

5 Area corresponding to current Serbia and Bulgaria.

6 A. Stipčević, The Illyrians: history and culture, Noyes Press, 1977, p. 76

7 F Curta. The Making of the Slavs. 2001, p. 189

8 The term "thema" designates the districts that were created in the XNUMXth century by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius I, in order to renew the administrative and territorial structure of the entire empire.

9 The Grand Prince is still considered the father of the Serbian nation, as he brought together the various Slavic entities of the Balkans in a single state.

10 A. Madgearu and M. Gordon, The Wars of the Balkan Peninsula: Their Medieval Origins, Scarecrow Press, 2008, p. 25

11 The League of Alexios, or League of Lezhë, was a defensive alliance of Albanian princes, formed in Lezha (Alexios) on 2 March 1444, as part of the rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. On November 28, 1443, Albania proclaimed its own flag, which still exists today, and declared independence from the Turks.

12 M. Sellers, The Rule of Law in Comparative Perspective, Springer, 2010, p. 207

13 Principle of use

14 M. Vickers, Chapter 1: Between Serb and Albanian, A History of Kosovo, New York Times, Columbia University Press, 1998

15 Essays: 'The battle of Kosovo' by Noel Malcolm, Prospect Magazine May 1998/30, prospectmagazine.co.uk

16 B. Jelavich, History of the Balkans, Cambridge University Press, 1983, p. 31