It was the record and absolute success of the High Speed Department, an elite school for sprinters, a "Top Gun" of other times, where it was taught to lead the seaplanes at speed, for the time, from chills.

But how did this record, still unbeaten, come in the piston engine seaplane?

Like any history worthy of the most glorious successes we start with a failure and the need for revenge and revenge. This story begins in 1912, when the Schneider Cup was established: an international competition between seaplanes aimed at encouraging aeronautical development, especially in the motor industry. In the mind of pilots and builders this competition, however, took on a different meaning. It was immediately clear, from the first editions, that the Schneider Cup would be, first of all, a race to the speed record.

The first edition of the 1913 disputed in the waters of the Principality of Monaco involved all the most technologically advanced countries in the aeronautical field and was won by a Frenchman, Maurice Prevost, with an average of 73,56 Km / h. The next edition of the 1914 was instead awarded to the English Howard Pixton, who aboard his Sopwith Schneider reached a speed of 139,74 Km / h.

The first edition of the 1913 disputed in the waters of the Principality of Monaco involved all the most technologically advanced countries in the aeronautical field and was won by a Frenchman, Maurice Prevost, with an average of 73,56 Km / h. The next edition of the 1914 was instead awarded to the English Howard Pixton, who aboard his Sopwith Schneider reached a speed of 139,74 Km / h.

With the outbreak of World War I, the cup was suspended and resumed only at 1919 in Bournemouth, England. Italian Guido Jannello driving a Savoy S.13 is the only rider to complete the 370km route. However, his victory was annulled by a race judge who challenged the Italian pilot to jump off a buoy. Unfortunately, because of the dense fog nobody was able to refute that decision. However, as a consolation prize, Italy was awarded the next edition of the cup, which was held in Venice, and which eventually saw the first time an Italian player, Luigi Bologna, who won the record on Savoia S.12 bis reaching the 170,54 Km / h. The following year, again in Venice, a new Italian success arrived, this time signed by Giovanni De Briganti with Macchi M.7 who beat the record with the speed of 189,66 Km / h.

The Schneider Cup rule stipulated that the trophy was definitively awarded to the country that won the competition three consecutive times. So Italy had ahead of him with the opportunity to finally win the trophy.

The 1922 edition took place on the waters of the Gulf of Naples. All eyes were on the Italian pilots. After the first sessions the French were eliminated and the race remained limited to three Italians and Englishman Henry Biard. Despite the numerical superiority of the Italians, the English turned out to be the winner, thus making the Italian triumph fade and reopening the race for the trophy.

The subsequent editions of the cup, namely Cowes (Great Britain) 1923 and Baltimore (USA) 1925 saw the United States triumph. The last Italian triumph of the competition reached the 1926, blocking the series of successes to "stars and stripes", with the Macchi M.39 piloted by Mario De Bernardi, which reached the 396,69 Km / has the previous record of 374,28 km / h.

The subsequent editions of the cup, namely Cowes (Great Britain) 1923 and Baltimore (USA) 1925 saw the United States triumph. The last Italian triumph of the competition reached the 1926, blocking the series of successes to "stars and stripes", with the Macchi M.39 piloted by Mario De Bernardi, which reached the 396,69 Km / has the previous record of 374,28 km / h.

The 1927 edition took place again in Venice, but the Italians were all put out of the race by a series of motor accidents. The English Sidney Webster on the Supermarine S.5 hydro-stroke had an easy life, and won the victory. This time the Italian disappointment was enormous.

In the public opinion there was a strong interest in Italian participation in the competition and many expected a new heroic success of the Italian wing. In addition, aviation was seen with great attention by fascist propaganda, the regime was deeply interested in showing the world the excellence of the national aviation industry and the triumph of the Schneider Cup was an absolute prerogative to achieve this goal.

Those were the golden years of aviation, the Regia Aeronautica was making a big contribution to writing the history of world aviation through the successes of its aviators. Just think of the enterprise of the 1921 by Arturo Ferrarin who completed the flight Rome-Tokyo and that of 1925 by Francesco De Pinedo, who together with the motorist Ernesto Campanelli, with a seaplane Savoia S.16 flew from Italy to Australia circumnavigating the latter, reached Tokyo and returned to the homeland. A flight of 370 hours for over 55.000 km flying over well 3 continents. To these successes, the regime, wanted and had to add the Schneider Cup and it is from this awareness that the project of a school of pilots, inside the Regia Aeronautica, that in collaboration with all the national aeronautical industries and with the best engineers, comes to life. could succeed in conquering, finally, the much sought-after trophy.

In the 1926 Italo Balbo had been appointed Minister of the Air Force and, after the defeat of Venice, decided to set up in 1928 the High Speed School based at the Desenzano del Garda hydro-boat under the command of Colonel Bernasconi, an officer with remarkable talents organizational. The school created a highly specialized team in which they cooperated, in close cooperation: pilots, engineers and industry.

In the 1926 Italo Balbo had been appointed Minister of the Air Force and, after the defeat of Venice, decided to set up in 1928 the High Speed School based at the Desenzano del Garda hydro-boat under the command of Colonel Bernasconi, an officer with remarkable talents organizational. The school created a highly specialized team in which they cooperated, in close cooperation: pilots, engineers and industry.

Despite the Italian efforts to go in the right direction, the only success that mitigated the Italian disappointments was that of Mario Bernardi, who with his Macchi Mc.52 was the first in the world to exceed the 500 km / h limit, for accuracy 512,776, earning the red "V" on his own Military Eagle, which was only awarded to those who exceeded the 500 Km / h speed.

De Bernardi was the only success, in fact, the British won the 1927 edition and the next edition of the Schneider Cup 1929. A further success of the British would end the games and finally deliver the triumph to the UK. We had to react with a new project with a new aircraft.

The Aeronautical Director had a challenge ahead of him that he could not avoid: to break the British victorious cycle and to challenge the Schneider trophy.

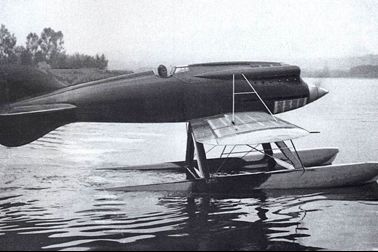

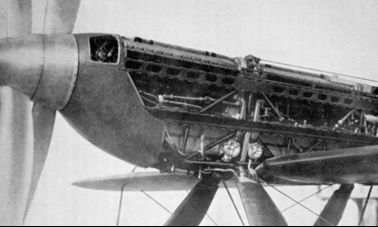

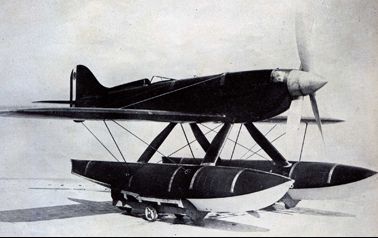

The 1931 edition represented the last chance to achieve this goal. To the engineer Mario Castoldi, father of the last hydroclaces Macchi Mc.39, Mc.52, Mc.67, the new project was entrusted. Castoldi immediately realized that the English were winning results because they had focused a lot on the reliability of the engine and the power it could generate. So he concentrated his work on the drive unit. As a first step he decided the formula, for the unusual era, of counter-rotating propellers, then he matched two Fiat AS 5 engines to 12 V-cylinders in a complex of well 51.256 liters of displacement with 3100 hp power.

This engine guaranteed enormous power and a series of additional advantages. An advantage was represented by the counter-rotating propellers, which being smaller in diameter involved aerodynamic benefits, moreover, again due to the smaller diameter, it was possible to optimize the size of the floats, since the risk of contact with the water surface was lower, obtaining so new benefits in terms of aerodynamics and therefore speed.

While Mc.72 Macchi was hoping, on the other hand, he showed great problems precisely because of his strength: the power of the engine. This engine needed a very complicated cooling system, but above all, it was the feeding system that gave the biggest problems, creating dangerous flame returns. To solve these problems, the group had to go into long and complicated work. All this resulted in the loss of valuable time to appear at the upcoming 1931 September Schneider Cup.

While Mc.72 Macchi was hoping, on the other hand, he showed great problems precisely because of his strength: the power of the engine. This engine needed a very complicated cooling system, but above all, it was the feeding system that gave the biggest problems, creating dangerous flame returns. To solve these problems, the group had to go into long and complicated work. All this resulted in the loss of valuable time to appear at the upcoming 1931 September Schneider Cup.

In fact, in April 1931, the High Speed School was still engaged in engine testing trials but could not generate the expected power of 3100 cv stopping at 2200. The first flight took place only on June 22 and engine problems continued to keep the group busy. Captain Giovanni Monti, who had the honor of bringing Macchi Mc.72 for the first time, was forced on an emergency landing for compressor breaks. The August 2, Monti, lost its life by flying in flight due to a failure of the counter-rotating propeller system. The tests were suspended and later carried out by the tenants Neri and Bellini, but it was now apparent that participation in the 1931 edition, fixed at the September 12, was seriously compromised. In addition, the 10 September lost its life in a test flight, with its Mac.72 Macchi, also Lieutenant Bellini, due to the plane's explosion.

Italy tried, in every way, to request a postponement of the date set for the 1931 Schneider Cup, but this request was always rejected. In that edition the English competed practically alone and finally won the Schneider trophy with the third consecutive victory.

Italy tried, in every way, to request a postponement of the date set for the 1931 Schneider Cup, but this request was always rejected. In that edition the English competed practically alone and finally won the Schneider trophy with the third consecutive victory.

But Italo Balbo was aware that thanks to the High Speed School's experience had achieved high technical knowledge and the aircraft could have won more successes, perhaps far superior to those of the Schneider Cup. In fact, there was still something to be able to conquer: the world's highest speed. The High Speed School was rethought, changed its name to the High Speed Department and addressed all the efforts to fine-tune the Mac.72 Macchi, eliminating first and foremost the problems related to dangerous flame retrieval. The goal was to beat the record set by Englishman George Stainforth in the 1931 edition of the Schneider Cup, ie beat the 655 km / h of his Supermarine S.6 B.

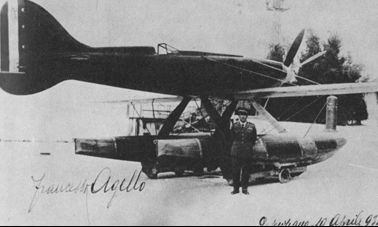

The 10 April 1933, after two years of intense work by the entire department, the Macchi Mc.72 was not just a plane with captivating lines, elegant and a beautiful aircraft dressed in a flaming red, but also a concentrate of power and above all reliability . The reliability that had been missing two years ago and that if it had been reached in time, it would have written a whole other story. The car was ready, it was time to choose the man. The choice fell on the marshal Francesco Agello, a veteran pilot of the High Speed School and an experienced test driver with excellent driving skills and professionalism. Everything was ready. On the morning of the 10 April Colonel Bernasconi took off, personally, to check the weather conditions, in particular the visibility on Lake Garda.

The 10 April 1933, after two years of intense work by the entire department, the Macchi Mc.72 was not just a plane with captivating lines, elegant and a beautiful aircraft dressed in a flaming red, but also a concentrate of power and above all reliability . The reliability that had been missing two years ago and that if it had been reached in time, it would have written a whole other story. The car was ready, it was time to choose the man. The choice fell on the marshal Francesco Agello, a veteran pilot of the High Speed School and an experienced test driver with excellent driving skills and professionalism. Everything was ready. On the morning of the 10 April Colonel Bernasconi took off, personally, to check the weather conditions, in particular the visibility on Lake Garda.

Agello was able to take off with the MM.177 hydrograph, performing five lake speeds at a mean speed that FAI inspectors calculated at 682,078 Km / h.

The English record had been beaten, the speed record was Italian. Finally the RAV men were rewarded with the years of efforts and sacrifices undertaken to achieve this great goal, so they could honor the pilots who had given their lives to make this venture possible, like Monti and Bellini.

But at the RAV the scent of victory did not extinguish the ambitions. Colonel Bernasconi, was convinced that the Macchi Mc.72 could reach higher speeds and exceed the 700 Km / h. Thus the 23 October of the 1934, Marshal Agello was called to beat himself. On board the MM.181 crossing, he made four passes on Lake Garda, touching the maximum speed of 711,462 Km / h, marking an average of 709,202 Km / h.

Another extraordinary page in the history of aviation was written, a page destined to last in time, a page that still, after eighty years, remains unbeaten.

Another extraordinary page in the history of aviation was written, a page destined to last in time, a page that still, after eighty years, remains unbeaten.

The history of this company has always generated a bitter reflection: it is incredible how in the 1934 the Italian aviation genius was able to develop an aircraft that still, for its category, remains the fastest aircraft in the world, but then, when the 1940 entered the war, he equipped our Regia Aeronautica with the agile, but modest biplanes, Fiat Cr.42.

Carmine Savoia