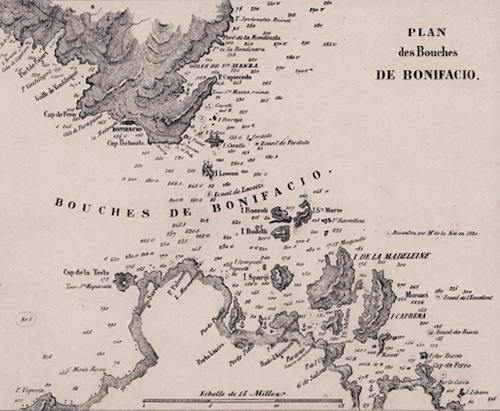

The mouths of Bonifacio separate Sardinia from Corsica and have, at their narrowest point, a distance of only 12 km. This has always favored trade between the two islands, also allowing Corsican shepherds to easily cross the strait to bring their flocks to graze in Gallura or on the islands of the archipelago of La Maddalena, which has seven major islands (La Maddalena, Caprera, Santo Stefano, Spargi, Budelli, Ralòli and Santa Maria) with a large number of smaller islets. They are all islands separated by small stretches of sea which are mainly unnavigable by medium/large vessels and this, if on the one hand it was a danger to navigation, on the other it represented a natural protection for those who stopped in the waters of the archipelago. to protect themselves from pirates or from the strong Mistral/Ponente wind which, due to the proximity of the two coasts, reached significant intensities.

In this context, the three major islands (La Maddalena, Caprera and Santo Stefano) form the most significant group, also because they border on navigable waters, which offer both good protection and possibility of monitoring the traffic passing through the mouths. The geographical position of the archipelago, in fact, has always been a source of attraction for those who had an interest in controlling (or developing) trade in that part of the Mediterranean. Being so close, the populations residing in Corsica and in the archipelago developed and then maintained numerous and fruitful relationships, from Neolithic times until the beginning of the XNUMXth century, when everything changed.

The background

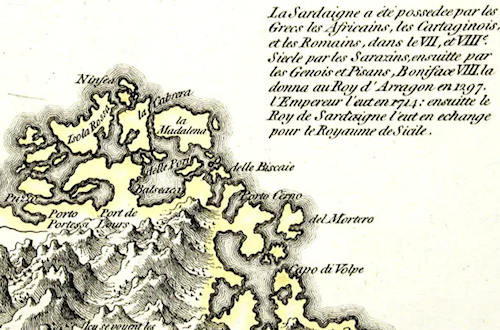

In 1720, in fact, Sardinia (with the archipelago of La Maddalena) was attributed to the Savoys, who until then knew neither the area nor the populations nor the islands of the archipelago. As Corsica was the "property" of Genoa, which at the time was not yet Savoy, some tensions began to flourish at a political level regarding the possession of the islands of the archipelago. Not among the inhabitants who, on the other hand, continued indifferent to weave commercial relations that were satisfactory for both sides.

Things began to get complicated in 1768, following the signing of the Treaty of Versailles with which Genoa, now bankrupt and which had long ago lost control of the island, sold its rights (sic!) to France under Louis XV. on Corsica, which was however independent de facto from 1755 (Pasquale Paoli). The French military occupation took place immediately by the troops commanded by Noël Jourda, Count of Vaux. However, the formal annexation took place later, four months after the storming of the Bastille (November 30, 1789), with an act of the French National Constituent Assembly.

The passage of Corsica to France completely changed the geopolitical framework of the area, given that the United Kingdom had continued to send aid to Corsica, placing itself once more as an antagonist of the transalpines. Although London had decided not to intervene, having clear the strategic value of the archipelago, it approached the Savoys, in order to allow it to maintain some type of surveillance on traffic through the Bocche di Bonifacio.

The strategic value of the La Maddalena archipelago was also very clear to the French who immediately set themselves the goal of controlling the two sides of the Strait, supported in this by the Bonifacini, who had never stopped asking their government to do everything possible to "regain possession" of those islands.

The strategic weight of the position and of the landings of the archipelago was therefore becoming clearer and clearer, even in the minds of the Savoyards who re-evaluated these strategic positions for trade in the area and began, with guilty delay, to build military defense works, which have now become undeferrable.

Military preparation and French aggression

The fear of an imminent French attack also accelerated the preparation of the crews of the Savoyard ships, among whose ranks many young La Maddalena soldiers fought, previously enlisted to fight against the incursions of the Barbary pirates, frequent and dangerous at the time. During these hard battles, the La Maddalena people covered themselves with glory for their courage and seamanship, earning themselves gold medals for bravery. These results are all the more important if one considers that the La Maddalena people, despite living on an island, had not until then acquired significant seafaring skills, having left these duties to the Campania and Maltese sailors who traded in the area.

In May 1792 the rumors of a possible French expedition against the archipelago and the Gallura coast, fundamental for the control of the strait and, therefore, of the Tyrrhenian Sea, became more insistent. The French decision-makers broke the delay the following December, also because they were supported by information from intelligence according to which the La Maddalena people would have been flattered by a possible annexation to Corsica and, therefore, to France.

In order not to miss anything, the French decided that northern Sardinia alone would not be sufficient, and prepared two expeditionary forces, one of which had the task of occupying Cagliari. As Giovanna Sotgiu writesi, it was about “…a notable but disorganized expeditionary force, with ragged volunteer troops who, hampered by the south-west wind, the coastal ponds and great inexperience, were forced to go back to sea after two months, defeated…”.

The other expeditionary force, more consistent and made up of 22 ships, landed in Santo Stefano carrying cannons and howitzers with which they began to bombard La Maddalena without stopping, which, from that position, was a rather easy target. Among the French Forces was a certain young artillery officer, Napoleon Bonaparte (image), who was then in command of the French batteries. Furthermore, from their position, the French prevented the people from La Maddalena from receiving reinforcements from Gallura as the island stood between La Maddalena and the Sardinian coast.

The other expeditionary force, more consistent and made up of 22 ships, landed in Santo Stefano carrying cannons and howitzers with which they began to bombard La Maddalena without stopping, which, from that position, was a rather easy target. Among the French Forces was a certain young artillery officer, Napoleon Bonaparte (image), who was then in command of the French batteries. Furthermore, from their position, the French prevented the people from La Maddalena from receiving reinforcements from Gallura as the island stood between La Maddalena and the Sardinian coast.

The French had left Bonifacio convinced that they would easily return victorious, thanks to the information received and the carrying out of aquick and painless action. The frigate was placed to support the French action Warbler, with the task of shelling the flank of the defenders.

The response of the Magdalenini

Two days after the attack, the ammunition of the defenders began to run dangerously low, but the indomitable nature of the Maddalena inhabitants did not give in to the noisy pressures of the transalpines. The commander of the square of La Maddalena then detaches a group of brave men, under the orders of boatmanii Dominic Millelire, which with a cannon must silence the artillery of the enemy ship. Which happens thanks to the precision of their shot, which forces the transalpines to seek shelter behind the island of Santo Stefano.

At this point the Millelire knows that La Maddalena will not be able to resist for much longer and, given the serious situation and the continuous and precise hammering by the enemy batteries, he takes the initiative and, having made other cannons arrive from the central square, he decides to pass to the counterattack against the French forces, decidedly superior and attested on better positions.

Despite the vigilance of the enemy, with a daring nocturnal action and on vehicles with limited capacity, he crosses the arm of the sea that separates La Maddalena from the Gallura coast and places two small batteries of cannons in positions such as to be able to hit the artillery commanded by Napoleon from behind and the cove where the opposing ships were anchored.

Thus, while the French were intent on bombarding La Maddalena, on 24 February 1793 the group led by Domenico Millelire suddenly began to strike the French, who found themselves from besiegers to besieged.

Once again the precise fire of the La Maddalena troops stationed on the Sardinian coasts had the effect of upsetting the enemy devices, throwing them into confusion. The French therefore found themselves in a difficult position, under enemy bombardment from La Maddalena and from the coasts behind them and without the possibility of making good use of the ships, blocked in the roadstead by the lethal cannonade from La Maddalena organized by Millelire.

As Giovanna Sotgiu always points outiii, “…the lack of discipline and military preparation of the volunteers (French, ed.) prevailed over all other considerations, dignity and duty and… they forced the withdrawal. Napoleon, who saw victory close ... objected and tried to resist, but disorder and anarchy now predominated forcing everyone to retreat or, if you prefer, to a dishonorable and disorderly escape ... " also leaving part of the armament on the island due to the hurry that the French were in to escape from what had now become a death trap. Napoleon vowed to return to finish the job, but history tells us that things turned out very differently.

Legend has handed down to us a Millelire who, not satisfied with the hasty escape of the aggressors, embarks on a gunboat and chases the enemy convoy almost as far as Corsica in its disorderly flight.

Domenico Millelire was acclaimed as a hero who, together with a few other brave men, had carried out actions of undoubted daring, assuming the burden of carrying out risky personal initiatives which had led to victory, saving the independence of the archipelago and, probably, all of Sardinia.

A humble helmsman, thanks to his courage and resourcefulness, he managed to close a leak in La Maddalena's defense system and to surround the aggressor, putting him in serious difficulty. His valor was adequately rewarded with numerous promotions, later also becoming commander of the port of La Maddalena, a prestigious position that he was able to carry out with dignity and competence. He is historically considered the first gold medal for military valor of the Italian Armed Forces.

The geopolitical consequences

The geopolitical consequences

The failure of the French attacks, which proved to be far from easy and rapid, had a positive effect on the morale of the Savoy and Maddalena crews and allowed them to influence the course of history, both in terms of the fight against the Barbary pirates and the collaboration with the navy of his British majesty.

The fight against the pirates, in fact, regained strength and, in an epic battle, two Barbary boats were sunk and the surviving enemies captured. In a nutshell, the valor and combativeness of the Madeleine sailors prompted the pirates to remain from that moment on at a respectful distance from the archipelago and the northern coasts of Sardinia.

But another problem loomed on the horizon. Napoleon's rise to power in France meant that he could keep the promise made at the time of his disorderly escape from Santo Stefano. On the continent, the clashes between the French and Savoy saw the latter lose ground and, therefore, the people of La Maddalena expected an attack at any moment. Added to this were the damages caused by the French corsairs, which prevented free trade on those waters. In short, everything worked in favor of further rapprochement with the British, both to ensure the archipelago a sort of unofficial protection and to ensure the continuation of merchant traffic, essential for the livelihood of the population.

Thus it was that Admiral Nelson's fleet, which arrived in the Mediterranean to counter the French one, made the archipelago of La Maddalena a privileged base for resting the crews and for its supplies, between a pursuit of the Bonapartist fleet and the subsequent . In fact, between October 1803 and January 1805, the English fleet stopped eight times in the calm and safe waters of La Maddalena bay, from where it was more convenient to supervise the French fleet, anchored in the port of Toulon. The archipelago, in fact, was only 24 hours of navigation from the important French port and this allowed the British to easily check and study the moves of the transalpines, allowing the crews a rest period and stocking up on fresh food.

Even if the famous English admiral never went ashore, he maintained excellent relations with the Magdalene authorities and, in particular, with Agostino Millelire (Dominic's older brother), who was often his guest aboard the Victory. As thanks for the hospitality received on October 18, 1804, at the end of the penultimate of his eight stops in the archipelago, Nelson presented him with an altar set (two candlesticks and a silver crucifix). The gift was accompanied by an autographed letter now kept, together with the altar equipment, in the Diocesan Museum of La Maddalena. The reply letter from the Magdalenini is now kept in the British Museum.

Even if the famous English admiral never went ashore, he maintained excellent relations with the Magdalene authorities and, in particular, with Agostino Millelire (Dominic's older brother), who was often his guest aboard the Victory. As thanks for the hospitality received on October 18, 1804, at the end of the penultimate of his eight stops in the archipelago, Nelson presented him with an altar set (two candlesticks and a silver crucifix). The gift was accompanied by an autographed letter now kept, together with the altar equipment, in the Diocesan Museum of La Maddalena. The reply letter from the Magdalenini is now kept in the British Museum.

final Thoughts

The French intervention of 1793 is the classic example of how military operations which, in the minds of planners, should develop in a simple, rapid and victorious manner, instead become a nightmare for the aggressor, when the will, the determination and the ability of those who defend themselves, even if outnumbered and outnumbered.

Domenico Millelire's courageous action prevented the conquest of the Tyrrhenian Sea by the French who, with control of that area, would have deprived the British fleet of a comfortable and safe port of support, very close to French waters/ports and to the area of operations. This allowed Nelson to avoid ports far from Toulon, which would have more busy Majesty's crews than him. Without those rest periods and without holds filled with fresh food (especially vegetables as scurvy was always the biggest threat to crews), almost certainly the British (however outnumbered)iv they would not have fought at Trafalgar with the same determination and impetus and, perhaps, they would not have beaten Villeneuve, victoriously closing the duel with the French for control of the oceans, which would have lasted undisputed until the First World War.

But the action of the Millelire was possible thanks to the strong bond that had been established between the crews of the Savoy navy and the population of the island, certainly favored by the presence of many Magdalenini on the king's ships. Today, that bond that unites the Maddalena people to the Navy is still alive and finds practical realization in the training of young helmsmen at the Officers' School of the Navy, which is based in La Maddalena (read the article "Mariscuola La Maddalena, between tradition and innovation")

Domenico Millelire maintained his humility in the years following his feat and never considered himself a hero, despite the acknowledgments he received, including the nomination to knight of the military order of Savoy, going down in history as the helmsman who defeated Napoleon.

i Giovanna Sotgiu, History of La Maddalena and its archipelago, Paolo Sorba Editore, 2022, p. 79

ii It is a term used to indicate who is in charge of the government and services on board a ship. He is assigned to the service of helmsman, to weigh the anchor or to the maneuvers of the tackles or the crane. It is also a fundamental part of the equipment of motorboats (master and bowmen).

iii Giovanna Sotgiu has taught in the high schools of La Maddalena and is a founding member of Co.Ri.S.Ma.

iv His British Majesty's fleet consisted of 33 units for a total of 2.136 guns. The allied fleet (France and Spain) fielded 40 units for a total of 2.894 guns.

Photo: web