From the red-hot Egyptian dunes, in the shadow of the Pyramids, General Bonaparte, together with his loyal helper General Louis Alexandre Berthier, looked worriedly over the horizon beyond the coast. The news coming from France was very bad: Paris was in turmoil, but what was even worse was the military defeats that followed each other at an impressive pace. The Austro Russian soldiers were spreading in northern Italy, helped by the masses of the people in revolt who shouted the soldiers of the Republic to the cry of "Viva Maria". The return from the sands of Alexandria in Egypt would not have been easy since the British fleet controlled the main routes of the Mediterranean, yet it was necessary to attempt the enterprise. The 22 in August 1799 the Corsican general wrote a heartfelt letter to Kléber confiding the command of the entire army while he boarded the frigate La Muiron accompanied by Jean Lannes, Gioacchino Murat, the artillery general Antoine François Andréossy and Auguste Marmont.

The prodromes of the battle

The more time passed, the more the rising star of Bonaparte took power: his establishment as Consul alongside Cambacérès and Charles François Lebrun was only the first act of a career that led him to dominate Europe. For France, from the military point of view, the 1799 closed in a disastrous way: the offensive of the Austrous Russian armies of General Aleksandr Souvarov were demolishing French rule in northern Italy and approaching dangerously the borders with France. The "Trees of Liberty" were overthrown and there was very little left of the victorious Italian Army of the 1796.

The 3 March 1800 Napoleon addressed a letter to the Minister of War Berthier communicating his intention to create the Army of the Reserve: "You will maintain the utmost secrecy on this decree, providing notice to all the persons appointed to be ready to leave and take all necessary measures to bring Dijon everything necessary to supply this army"1. The town of Dijon was chosen as the headquarters of the headquarters, while Auxonne as a collection point for the artillery park.

In the general vision of Bonaparte the new army had to help troops in trouble on the Italian front where General André Masséna, now isolated between the borders of the Ligurian Republic, was defending with a few men, but so much courage, that thin strip of land that separated the Austrians of the General Mélas from Provence. The central point of this obstinate resistance was Genoa, the next theater of a dramatic siege. Napoleon had to hurry because if the capital of the Republic had fallen, it would have paved the way for the Austrians; it was necessary to surprise the troops of Mélas and beat them in a single and decisive battle.

In the general vision of Bonaparte the new army had to help troops in trouble on the Italian front where General André Masséna, now isolated between the borders of the Ligurian Republic, was defending with a few men, but so much courage, that thin strip of land that separated the Austrians of the General Mélas from Provence. The central point of this obstinate resistance was Genoa, the next theater of a dramatic siege. Napoleon had to hurry because if the capital of the Republic had fallen, it would have paved the way for the Austrians; it was necessary to surprise the troops of Mélas and beat them in a single and decisive battle.

The passage of the Alps

The plan of the First Consul foresaw the application of one of the fundamental principles of Napoleonic tactics, namely the Manoevre sur le derrières. Through this maneuver, in which the speed and secrecy of the movements counted above all, Napoleone engaged his adversary without letting himself be involved in a font battle, and then surprised him with an enveloping maneuver, behind him as he tried to retreat. The march of soldiers destined to break into the enemy's fold line was secretly hidden by cavalry shields and natural barriers whose only crossing points were manned2. In this way the opposing armies, seeing the escape route precluded, became demoralized and it remained for them only to surrender. To obtain an immediate success on the Austrians of Mélas it was indispensable that General Massena resisted behind the walls of Genoa for as long as possible; if the city had fallen, the Austrian commander would have had one more chance to retire, aided by British boats off the harbor3. The First Consul had to exploit the surprise factor guaranteed by the risky passage of the Alps in a month when the passes were still blocked by the snow.

Emil of Hannibal, 15 May 1800, the future emperor of the French marched towards the Great St. Bernard: there was no time to lose because the news from Liguria worsened from day to day4. Unlike the great painter Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Bonaparte crossed the Alps on the back of a mule: certainly less fascinating than a white steed, but more functional and above all credible. Exposed to continuous avalanches and avalanches, the most difficult thing for the soldiers was to transport the artillery. Each piece was broken down by the wooden barrels and loaded into pieces: the heavy gauges were placed inside the dug trunks and let slip - with the help of ropes and levers - towards the valley. In the memoirs of Captain Jean Roche Coignet, at the time simple grenadier of the 96 ° line, the passage of the Saint Bernard is described with scrupulousness: "We put our three pieces of cannon in deep cones. At the bottom of those basins there was a large mortise to fit a lever that served as a rudder to guide our piece, ruled by a strong and intelligent gunner. With the most absolute silence we had to obey him in all the movements that his piece could do"5. Each gunner's leader formed a team of forty grenadiers for each cannon "twenty to pull the piece (ten on each side with a stick across the rope that served as an extension) and the other winds carried the rifles of the first who pulled the piece"6.

Emil of Hannibal, 15 May 1800, the future emperor of the French marched towards the Great St. Bernard: there was no time to lose because the news from Liguria worsened from day to day4. Unlike the great painter Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Bonaparte crossed the Alps on the back of a mule: certainly less fascinating than a white steed, but more functional and above all credible. Exposed to continuous avalanches and avalanches, the most difficult thing for the soldiers was to transport the artillery. Each piece was broken down by the wooden barrels and loaded into pieces: the heavy gauges were placed inside the dug trunks and let slip - with the help of ropes and levers - towards the valley. In the memoirs of Captain Jean Roche Coignet, at the time simple grenadier of the 96 ° line, the passage of the Saint Bernard is described with scrupulousness: "We put our three pieces of cannon in deep cones. At the bottom of those basins there was a large mortise to fit a lever that served as a rudder to guide our piece, ruled by a strong and intelligent gunner. With the most absolute silence we had to obey him in all the movements that his piece could do"5. Each gunner's leader formed a team of forty grenadiers for each cannon "twenty to pull the piece (ten on each side with a stick across the rope that served as an extension) and the other winds carried the rifles of the first who pulled the piece"6.

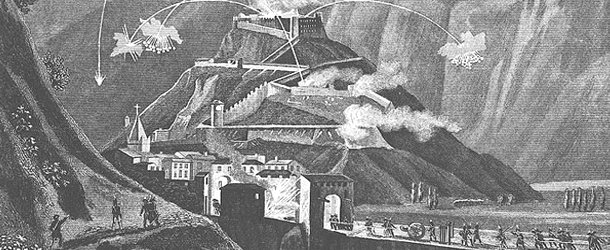

The first real impediment, however, occurred in front of the fortress of Bard that, guarded by the Austrians of the captain Stockard von Bernkopf, barred the road to the French 40.000 of the Reserve Army. After some unsuccessful attempts, General Berthier received orders from Bonaparte for the fortress to be bypassed thanks to an alternative passage represented by Mount Albaredo. In just two days 500 soldiers dug the rock, making their way with picks: ladders were made and new paths with bridges connecting.

The problem concerned the artillery, which certainly could not move from those steep and landslide paths.

General Marmont and the general of the genius Armand Samuel de Marescot ventured to place cannons on high positions, but without any success: the situation was increasingly dangerous because in the narrow valley the French were forming a stopper with no way out. In his memoirs Marmont - future marshal of the Empire - mentioned the difficulties of that enterprise: "That path presented even more sinuosity and consequently much greater difficulties than that of the Saint Bernard"7. He was also ordered to disassemble the guns for the umpteenth time, running a risk on the future functioning of the pieces: "If you can get by so much care you will no longer have to rely on this very bad material, being disjointed many parts and not very solid as a consequence of the operations already performed. If you dispose of beautiful again it will no longer be good for nothing".

After some assaults rejected by the defenders, General Berthier tried to play cunning by passing men and artillery from the nearby village of Bard, a few meters from the fortified walls, concealing their movements with artificial smoke. The French soldiers collected straw and anything else to light fires: it was necessary to act in complete silence and at night. Unfortunately for Berthier the Austrians were vigilant and as soon as the first French were sighted, a fiery hell rained down on them. The fight was hard, but although the French losses were high, most of the cannons crossed the obstacle, leaving behind the Bard massif.8. Once bypassed, the fortress was laid siege and the 1 ° June commander von Bernkopf surrendered surrender to the French.

Three days after the fall of Bard, a more important stronghold yielded weapons to the enemy: the 4 June 1800, on the bridge of Cornigliano, General Massena surrendered to the Austrians. Napoleon had to change course and hurry to Alexandria if he wanted a decisive confrontation with Melas.

The plain of Marengo

The stalemate caused by the fort of Bard and the worry that the artillery did not arrive in time for the battle convinced Napoleon to point towards the east, in the direction of Milan. He entered the city triumphantly in the hope of finding the artillery park intact and in the meantime being reached by the body of General Moreau from the Gotthard. Discarded the possibility of occupying Stradella served absolutely block the road to the Austrians of Mélas bringing the main attack force to Alexandria. On the afternoon of the 13 June, the Reserve Army began to line up in the Marengo plain with an actual total of about 31.500 men. The Austrian commander, far from accepting a clash in the open field - a serious mistake according to Napoleon because he would have precluded the use of the cavalry - moved back to the Citadel of Alexandria, perhaps for fear of the French troops of Suchet and Massena from the south. At this point it was Napoleon who made a mistake by fragmenting his forces; he decided to send two contingents, under the command of General Lapoype and Desaix, in order to close any lines of retreat to the enemy. In possession of small forces (about 23.000 men), the First Consul suffered the surprise of Mélas when he crossed the three points on the Bormida to attack him in front of Marengo. Napoleon thought it was a diversionary skirmish so as to support the Austrian retreat, however around the 11 in the morning and after repeated attacks it became clear that Mélas was anything but willing to fall back. The generals Jean Lannes, Giocchino Murat and Claude Victor were opposed to the Austrian pressure with just 15.000 men, and suddenly, towards the 11 the situation precipitated. The only employable reserve was barely counting on 900 Consular Guard men, the Monier division and part of the cavalry, while the Austrian general Peter Karl Ott marched briskly with 7.500 men towards the French right flank, who risked being encircled. Napoleon began to worry and consequently ordered that Desaix and Lapoype return back to join the Marengo field. A defeat would have meant the end of the campaign, but not only: although General Bonaparte could bear such an eventuality, the political leader could not afford to make mistakes9.

After a brief pause by the Austrians to close the ranks, the attacks resumed more vigorously and around the 15,00 the battle seemed to have been lost with the French deployment that was moving back towards Torre Garofoli. But just when all the dreams of glory seemed to have vanished, two events occurred that changed the fate of the day: General Mélas imprudently left the command to General Zach, while Charles-Antoine Desaix arrived in Marengo with a reinforcement of about 5.000 men. The First Consul, surprised by so much luck, ordered his trusted friend to counteract the Austrian lines vigorously: at 17.30 at the head of 9a demi-brigade légère the young Desaix overturned the barrage of the Austrian infantry regiments of Wallis and Kinsky. Unfortunately during the advance, near Vigna Santa, Desaix was reached by a deadly shotgun.

After a brief pause by the Austrians to close the ranks, the attacks resumed more vigorously and around the 15,00 the battle seemed to have been lost with the French deployment that was moving back towards Torre Garofoli. But just when all the dreams of glory seemed to have vanished, two events occurred that changed the fate of the day: General Mélas imprudently left the command to General Zach, while Charles-Antoine Desaix arrived in Marengo with a reinforcement of about 5.000 men. The First Consul, surprised by so much luck, ordered his trusted friend to counteract the Austrian lines vigorously: at 17.30 at the head of 9a demi-brigade légère the young Desaix overturned the barrage of the Austrian infantry regiments of Wallis and Kinsky. Unfortunately during the advance, near Vigna Santa, Desaix was reached by a deadly shotgun.

The office of Kellermann

One of the decisive events that turned the defeat of the French into a historic victory was the charge of the cavalry of General François-Étienne Kellerman. They were the 18,00, but the days of June still guaranteed a few hours of light so they could continue fighting and allow the Austrians a strategic retreat. Shortly before Desaix's death, Commander Kellerman was ordered to charge his opponent as soon as possible, in order to break the deployment. The 2 °, 20 ° and 21 ° cavalry regiment together with the 1 °, 8 ° and 9 ° Dragons threw themselves on the imperial grenadiers of General Christof Lattermann, supported by the fire of 16 cannons of General Marmont10. "Three battalions of grenadiers and the entire Wallis regiment were sabotaged and captured"- recalls in his memoirs the son of Commander Kellermann -"the citizen Riche, knight of the 2 regiment, took prisoner a general of the General Staff together with the loot of six flags and 4 pieces of artillery"11.

The battle was won, but that day had cost Napoleon many men including one of his dear friends, General Desaix. Just the same general companion of a thousand adventures in Egypt and who had escaped several times to the sad fate; shortly before dying, mindful of the dangers escaped from the sands of the desert, he seems to have whispered: "I fear that the balls of Europe no longer recognize me"12. The 15 June 1800 Napoleon sent a letter to the consuls Cambacérès and Lebrun: "The army news is very good. I can not tell you anything else, I am afflicted by a deeper pain for the death of the man whom I esteemed and loved more"13. For the burial of that brave man was chosen a symbol of the entire countryside, the pass of the Great St. Bernard where even today a plaque consecrated to him recalls his courage.

The battle was won, but that day had cost Napoleon many men including one of his dear friends, General Desaix. Just the same general companion of a thousand adventures in Egypt and who had escaped several times to the sad fate; shortly before dying, mindful of the dangers escaped from the sands of the desert, he seems to have whispered: "I fear that the balls of Europe no longer recognize me"12. The 15 June 1800 Napoleon sent a letter to the consuls Cambacérès and Lebrun: "The army news is very good. I can not tell you anything else, I am afflicted by a deeper pain for the death of the man whom I esteemed and loved more"13. For the burial of that brave man was chosen a symbol of the entire countryside, the pass of the Great St. Bernard where even today a plaque consecrated to him recalls his courage.

The 14 June 1800 sun set on a bloody day, but destined to enter the myth of imperial historiography. Just a few years later, in December of the 1805, another clash, in Austerlitz, upset the fate of Europe, nevertheless Marengo always occupied a privileged place in the heart of Napoleon, until his departure on the desolate rock of Sant'Elena.

The Marengo Museum

For those who want to relive the highlights of the 1800 campaign, the Museum of the Battle of Marengo offers an interesting perspective of what happened on 14 on June 1800. The well-equipped museum rooms with striking iconographic reproductions cover the days that brought Napoleon Bonaparte to triumph. The museum is a rare pearl in the small museum panorama dedicated to the Napoleonic era in Italy, above all because, after alternating events, the local authorities have been able to re-evaluate it by constructing a modern and impressive structure.

1 The decree for the Army of the Reserve was dated 8 March 1800; the new unit was destined to provide reinforcements both to the Armata d'Italia of General Massena and to that of the Reno of General Moreau. Napoléon Ier, Correspondance générale, Paris, Fayard, Tome III, p. 119.

2 Hubert Camon, The Napoléonienne Wars. Les systèmes d'opérations théorie et techniques, Paris, Economics, 1997, pp. 33-34.

3 For a detailed description of the plan see David Chandler, Change historical memory: Napoleone and Marengo, in Vittorio Scotti Douglas (edited by), Europe discovers Napoleon 1793-1804, Proceedings of the Napoleonic International Congress (Citadel of Alexandria, 21-16 June 1997), Vol. II, p. 868.

4 The initial plan foresaw that Napoleon would pass through the Sempione or the San Gottardo, but the news from Genoa forced him to change his mind and to throw himself from the Valle d'Aosta directly onto Genoa via Alessandria. The Napoléonienne Wars, op. cit., p. 84.

5 Jean-Roche Coignet, The memories of Captain Coignet, Milan, Longanesi "I Cento Libri", 1970, p. 121.

6 Ibidem.

7 Marmont, Memoirs of Marshal Marmont Duke of Ragusa. From the 1792 to the 1841. First Italian translation for Emprando Framarini, Milan, Francesco Sanvito Libraio Publisher, 1857, p. 272.

8 Victoires, conquetes déstastres, revers et guerres civiles des français, Paris, Au Bureau des Publications Illustrées, 1840, vol. VII, p. 31.

9 Bruno Ciotti, La dernière campaigns de Desaix, in Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 324, avril-juin 2001, URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/381#ftn46.

10 Digby Smith, Charge. Great Cavalry Charges of the Napoleonic Wars, London, Greenhill Books, pp. 43-44.

11 Duc de Valmy, Histoire de la Campagne de 1800, Paris, Dumaine, 1854, p. 181.

12 Marmont, op. cit., p. 280.

13 Correspondance générale, op. cit., p. 301.

(photo: web / Marengo Museum)