The "Premier Mine", owned by the diamond company Petra Diamonds, located in the city of Cullinan, 40 km. east of Pretoria, is famous for the discovery, in 1905, of the Cullinan diamond which, weighing 3.160 carats, is the largest rough diamond ever discovered.

In 1907 the South African government offered the stone to Edward VII, King of England, on the occasion of his 66th birthday as a sign of gratitude to the sovereign for the autonomy recently granted. Subsequently the stone was divided into nine huge diamonds and in particular were obtained:

- the Cullinan I or Great Star of Africa (530 carats) which adorns the British imperial scepter known as the "Scepter of St. Edward";

- the Cullinan II (317 carats) mounted on the imperial state crown.

I had the pleasure of seeing them both, displayed in the Tower of London with all the British Crown Jewels.

Well, on land adjacent to this famous mine, in an amphitheater-shaped wasteland called Sin water (which in the Boer language means "without water"), the English, thanks to an agreement with the South African ally, began to convey the first prisoners from the fronts of Eritrea and Cyrenaica; already after the battle of Sidi El Barrani (December 1940), General Archibald Percival Wavell, commander of the Operational Theater which included all of Africa and the Middle East, found himself having to manage thousands of prisoners that security reasons required to remove from those scenarios in continuous and rapid change, too close to the areas of operations, with the frequent alternation of reciprocal advances and withdrawals.

But let's go back to that end of January 1941, surroundings of Tobruk: for convenience I will refer to places and dates concerning the group in which my father was inserted, implying that the facts were replicated in the same way also for other prisoners.

In the previous piece (v.articolo) we had left the twenty thousand defenders of the Piazzaforte, stripped by the Australian soldiers of all their possessions or personal memories, set out on foot, in long distinct columns of about two thousand men each, towards the port of Sollum (photo); the injured and a few more fortunate ones were also herded into trucks (about twenty per vehicle).

For everyone it was a humiliating, inhumane and contrary to the Geneva conventions; for five days neither food nor water was distributed and dozens of prisoners died of dehydration. Despair arose and the less fussy eaters, including my father, at the suggestion of someone who boasted knowledge of medicine, collected their urine in the bottle and then drank it at night, cool, when the temperature dropped significantly; has always been one of the first things my father told to those who asked him what his imprisonment was like (consequently, the fear that he lacked water haunted him throughout his life: he always drank greedily and immoderately and wherever the first thought went was to bring water in tow).

At Sollum two thousand were put on ships that could carry a thousand. Once in Alexandria in Egypt, after about a day of navigation, they were loaded onto goods trains for transporting livestock and transferred to the various sorting camps along the Suez canal.

My father was assigned to camp 306, in the Geneifa area, a few hundred meters from the canal along the road that leads from Ismailia to Suez. The field consisted of about thirty so-called "cages" of 100x100 m. surrounded by a fence with the guards walking around and illuminated at night by photoelectrics. Each cage could accommodate up to three hundred prisoners.

Inside the cages were mounted conical tents with a circular plan, with an iron pole in the center, where one went to sleep, eight per tent, clothed in cloth and full of lice.

We slept arranged radially with the feet towards the pole; to combat the sweltering heat, the prisoners tied a string to their foot connected to the inner sheet of the tent and in turn pedaled to create the fan effect!

There were two distribution shifts for water, from XNUMXpm to midnight and from one to two in the afternoon; you had to make it enough because then the taps remained closed all day.

In the meantime the disinfestation had begun; prisoner clothing was distributed and the old Italian Army uniform was withdrawn and burned along with the lice.

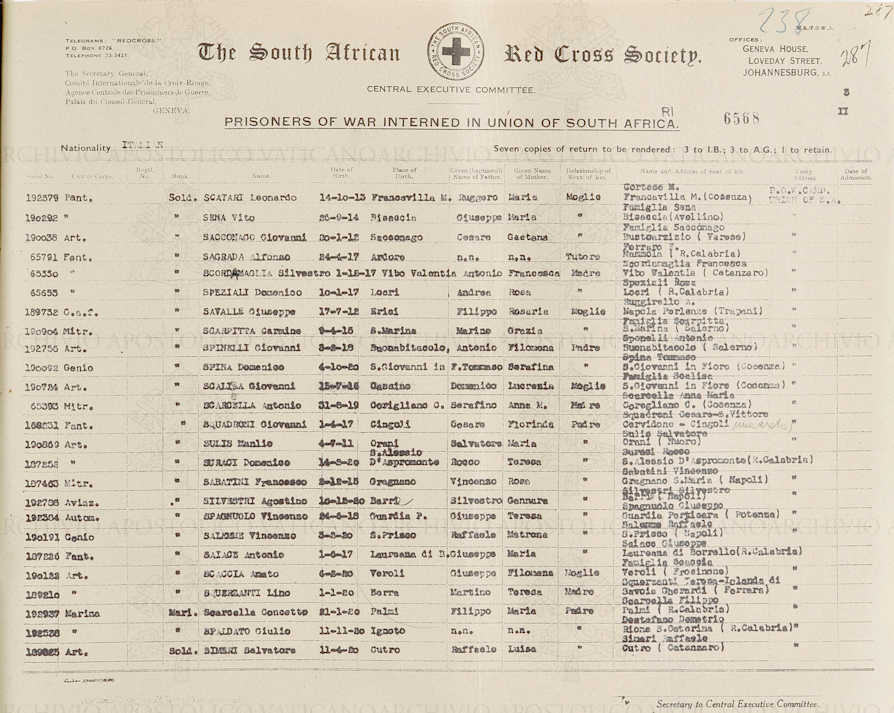

The ritual interrogations also began which ended for each one with the assumption of the juridical status of Pow (Prisoner of War) and the assignment of a serial number.

The ritual interrogations also began which ended for each one with the assumption of the juridical status of Pow (Prisoner of War) and the assignment of a serial number.

The food consisted almost exclusively of a "soup" of lentils, chickpeas or beans while for breakfast they distributed tea, a piece of bread and, sometimes, a spoonful of jam. From time to time they gave a can of meat to divide in two and in this case it was advisable to go to the line with a trusted friend: one took the box and the other collected the bread. Fights between prisoners were not infrequent because whoever collected the box, dishonestly, tried to make him lose track.

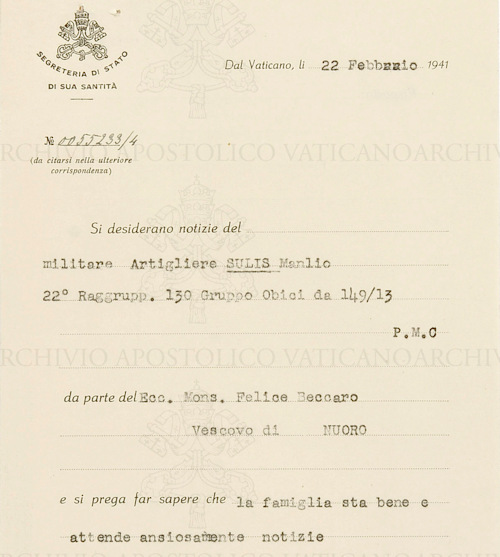

Meanwhile, news of Tobruk's fall had also reached Sardinia; as usual my father was reported missing and my grandmother, to get news, turned to the parish priest of the country who in turn activated the bishop who in turn interested the Vatican (photo).

On April 29, 1941, three months after the capture, a group of about 1500 prisoners were boarded in Suez for South Africa.

The steamer, following the route of the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean, with stops in Aden (Yemen) and Mombasa (Kenya), landed in Durban after fifteen days.

From the port of Durban, on foot, they were transferred to the transit-camp of Clairwood on the outskirts of the city: here a second disinfestation took place with complete shaving of beard and hair and distribution of other clothing. Then I board the trains to reach, after two days of travel and 600 km of railway, the final destination: Sin water. The calendar marked June 2, 1941, and winter had begun in the Transvaal region.

The camp, opened in April 1941, when my father arrived, contained about twenty thousand Italian prisoners.

The barracks had not yet been built and the prisoners had to sleep in the usual eight-person circular tents with an iron pole in the center: very dangerous because when it rained it attracted lightning and several prisoners died because of this as the storms were frequent and sudden. .

The behavior of the guards was very gruff and the food absolutely inadequate; the diaries and letters of prisoners who escaped censorship testify to this, but in particular the neutral reports of the International Red Cross.

For breakfast they gave coffee and milk with a piece of bread, for lunch and dinner a piece of bread, fruit, vegetables and, alternatively, a ladle of polenta or broth with a piece of meat, potatoes ... sometimes a little of cheese. Every day they also distributed 5 “Springbocks” cigarettes which non-smokers traded for food.

In the meantime my grandmother (it was August 1941) received from the Red Cross, via the Vatican, news that her son was alive, interned in South Africa (following photo).

Meanwhile, the number of prisoners from the war theaters of North and East Africa was increasing month by month.

The turning point came at the end of 1942 when a sensitive and enlightened personality such as South African colonel Hendrik Frederik Prinsloo was sent to direct the camp; of Boer origin, confined as a child with his mother in an English concentration camp in the war that had seen them opposed to the Boers, he had experienced firsthand the harshness of segregation and deprivation.

With foresight and concreteness he started the construction of roads and brick shacks, canteens, theaters, schools and gyms where the prisoners could avoid boredom and prostration.

In its final configuration, the camp came to accommodate over one hundred thousand Italian prisoners. It was a small prison town divided into 14 blocks: each block had 4 camps of 2000 men each. Coordinated by an Italian non-commissioned officer reporting to a South African counterpart, each camp had 24 tin roofed barracks. Each block was fenced off by barbed wire and guarded by armed guards on the rooftops; colored guards circulated along the fence, equipped only with spears or sticks, perhaps because they were considered unreliable by the white South African soldiers. Inside the block you could move freely but you could not pass from one block to another.

Until 8 September 1943, the division into blocks was made on the basis of certain ideological criteria in order to avoid understandable tensions between prisoners according to different political orientations; in fact some had chosen to collaborate with the keepers by obtaining permission to go outside the field for work mainly in agricultural activities, others, believing they had to keep faith with the initial oath, preferred not to collaborate while waiting for repatriation in more precarious general conditions and food. However, even the food improved significantly in such a way as to be defined as "excellent and abundant", certainly higher than what was distributed to Italian comrades on the war fronts.

Thirty kilometers of roads connected the shacks with the canteens (3-4 per block), the 17 theaters, schools for the illiterate or for those who wanted to study English. 16 football fields, volleyball and basketball facilities were built; among the hundred thousand there were also national and European athletes in various disciplines. In this regard my father, a boxing enthusiast, told of the double match organized in the spring of 1943 between two professional boxing prisoners; he did not remember the names but I later discovered they were Verdinelli and Manca, refereed by Lieutenant Stevens, South African champion, which was attended by a large audience but also the local press1.

Manca won both matches and then challenged the South African champion; The match, which was causing a great deal of debate in the local press, was never authorized for obvious reasons of expediency.

Literary and craft activities were organized with exhibitions and prizes for the best; periodically newspapers / newsletters in Italian were also published, edited by the prisoners themselves. Hospitals were built for a total of 3000 beds (photo) where each department was directed by Italian medical officers, some who later became very famous. Little by little, chapels or real churches were also built where the military chaplains tried to maintain that minimum of discipline necessary in the absence of the officers intentionally interned in India in disregard of the Geneva Conventions.

All this was possible thanks to the far-sightedness of Colonel Prinsloo but also to the activity of the International Red Cross as well as to the presence in South Africa of a large Italian community that actively collaborated in the field of assistance committees that were gradually forming to make life less burdensome. of fellow prisoners.

It can be observed that we have focused only on some positive aspects of what some historians have defined as a "good imprisonment" compared, for example, to that reserved after 8 September by the Germans for interned Italian soldiers; it was and remains, however, a story of deprivation of freedom which, for those who suffered it, was nevertheless destructive and unsustainable. It is obvious that within the camp there were also acts of coarseness and arrogance, fraudulent episodes between "gangs" or facts of real crime. However, we believe that they belong more to incivility than to history.

It can be observed that we have focused only on some positive aspects of what some historians have defined as a "good imprisonment" compared, for example, to that reserved after 8 September by the Germans for interned Italian soldiers; it was and remains, however, a story of deprivation of freedom which, for those who suffered it, was nevertheless destructive and unsustainable. It is obvious that within the camp there were also acts of coarseness and arrogance, fraudulent episodes between "gangs" or facts of real crime. However, we believe that they belong more to incivility than to history.

Of the hundred thousand, 252 did not have the good fortune to return home; died from accidents or illness and are now buried in a cemetery which, together with a Museum, a Chapel and a monument called the "Three Arches", constitute all that remains after in 1947, with the departure of the last prisoners, the camp was dismantled.

A worthy association called "Zonderwater Block ex Pow" chaired by Dr. Emilio Coccia, a highly esteemed engineer from Parma who has lived and worked for several years in South Africa, has obtained from the South African government the right to the perpetual use of the Shrine and to the management of the Museum where documents, objects and memories of that time and of those facts are kept.

Every year, at the beginning of November, the Italian community and the Diplomatic Authorities of the two countries meet to commemorate the 252 fallen but also the more than one hundred thousand soldiers who sacrificed part of their youth thousands of kilometers away from Italy.

The gunner Manlio Sulis, born in 1911, Pow 190869, interned in block 4 - field 16, left Zonderwater with 444 other prisoners on 24 August 1944, setting sail from Cape Town on the SS “Nieuw Amsterdam” motor ship for the United Kingdom.

The fear of torpedoing by German submarines accompanied the prisoners all the way (tragic news of the sinking of the ocean liner "Laconia" - September 12, 1942 - which left Cape Town and headed for Great Britain in 1800 Italian prisoners while sailing off the African coast near the island of Ascension and the sinking of the "RMS Nova Scotia" - on November 28, 1942 - by the German submarine U-177 about 150 miles from Durban, with 769 prisoners Italians from East Africa).

They landed in Glasgow on a date which I could not ascertain, presumably at the end of September; it is certain that on 14 October 1944 my father was registered at the entrance to Mellands Camp n.126 in Manchester with the new registration number 162782. He remained in Great Britain until his repatriation on 11 February 1946.

A question arises: why were the Italian prisoners in the hands of the British not released after September 8, 1943, considering that on that date we became "co-belligerents" or allies? Why did the British government refuse to repatriate them even after the end of the conflict, so much so that most of them returned to Italy only in late 1946?

The answer… will be in another story!

Giovanni Sulis (general of ca on leave)

1 Gino Verdinelli former Italian welterweight champion / Giovanni Manca (1919-1982) East African champion and Italian middleweight champion / Lawrence Stevens (1913-1989) South African lightweight champion and gold medalist Los Angeles Olympics (1932).

Photo: author