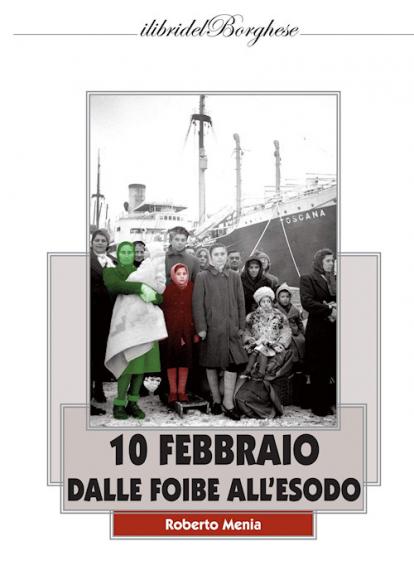

Robert Menia

Ed. Il Borghese, Rome 2022

Pag.306

“This book is a collection of stories. Stories of a world that no longer exists, of places that are no longer recognized for what they were and remain only places of the soul, of men and women, children of a people now dispersed from Italy to the other side of the world. ” So Senator Menia introduces us to this book of his, divided into sixty stories that have a common thread: the atrocities committed by the Tito communists - on which, for years, there has been an absurd silence - against “thousands of people barbarously killed in sinkholes guilty only of being Italian or of being servants of the state. A black page especially for Italy that has forgotten its children” started with “the political, military and institutional disbandment that followed 8 September 1943 which left the populations of Istria at the mercy of the advance of Tito's Yugoslav partisans who for over a month raged against anything Italian. That first wave of infoibamenti and massacres, which ended thanks to the re-establishment of Italian state garrisons, was followed by a second one at the end of the war when, from May 1945, the people of Tito, undisputed masters of the situation from Trieste to Gorizia, Pula, Fiume and Zara, completed their design of denationalization and ethnic cleansing against the Italians, with further massacres, infoibamenti, violence, abuses that continued in the ceded territories even several years after 1945 and will cause the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Italians.

To this must be added "the scandal of infoibatori who received the INPS pension which is another of the shames always kept silent by this Italy."

The first story is dedicated to Norma Cossetto, a 23-year-old girl - who lived on the Istrian peninsula, in Santa Domenica di Visinada - guilty of being the daughter of Giuseppe, mayor and former militia officer. The Tito communists, not finding her father in her house, took her away. The night between 4 and 5 October 1943 “Norma and the other prisoners, tied together with wires, were taken on foot to the foiba of Villa Surani, a ravine 136 meters deep, and here they were plunged, still alive.” Before this happened, according to the testimony of a person who lived near the place where she was imprisoned, Norma was raped by the Tito communists. When her body was recovered, she had Norma “a piece of wood stuck in the genitals”.

“Concept Marchesi, a communist professor and deputy of the constituent assembly, rector of the University of Padua, wanted to award Norma Cossetto an honorary degree: and, to those who objected to him that she was not an anti-fascist, he replied that she was worthy of it because died for being Italian.” In 2005 the President of the Republic awarded her the Gold Medal of Civil Merit in memory.

There are those who were forced, like Giuseppe Cernecca, to carry themselves “on his shoulders the cross of his Calvary: a heavy sack of stones with which they would have stoned him.” After having massacred him with stones, the Tito communists beheaded him and took his head to a watchmaker to have him extract two gold teeth.

It was Arnaldo Harzarich, marshal of the Pola fire brigade who recovered many foibati bodies, who became, for the Istrians, the Angel of the sinkholes while, for the Tito partisans, he became the target of threats.

October 31st was the last day of Italian Zadar, the capital of Dalmatia. “There were no sinkholes in Zara. But the sea. The partisans chose drowning as a method to make the victims disappear.” There Nicolò Luxardo was assassinated and was confiscated "the ancient Luxardo factory that had made Zara famous throughout the world for its Maraschino." In Malga Bala (now in Slovenia) twelve carabinieri were killed just because they were Italians. Vice-brigadier Perpignan was hanged "upside down tied to a beam so that he could see the torture of his men" who were slaughtered with a pickaxe. “Finishing a man with a pickaxe was a system which, in the communist code of the time, meant absolute contempt, humiliation, annulment… Someone had their genitals removed and stuck in their mouths. Others had their hearts and eyes taken away.”

River, now disappeared from the national memory, “offered to the motherland an enormous tribute of lives and examples that must not be lost,” Despite, “in order not to annoy its Croatian neighbor, its Italian name is not even pronounced anymore because today it is called Rijeka.” An example for all is that of the eighteen-year-old Giuseppe Librio, shot in the back of the head by the Slavic partisans because, having climbed the flagpole in Piazza Dante, "tore down the red white blue flag and fluttered the tricolor of Italy again."

When the Big Four Inter-Allied Commission went to Istria to assess the population's willingness to be annexed to Yugoslavia, the children were taught to shout Tito alive and raise their clenched fists. “But when they were in front of the commission cars, the children unclenched their little fists and the palms of their hands painted red, white and green appeared. [...] In Pazin, a note sent by an anonymous hand to the delegates of the Commission said: since you cannot interrogate the living, interrogate the dead. There were those who understood and asked to go and see the cemetery where, as in all of Istria, the vast majority of graves bore Italian names. From that day on, ethnic cleansing also began in cemeteries and thousands of Italian gravestones were destroyed."

On August 18, 1946, at 14 pm, the sun went dark in Vergarolla. “Suddenly a huge detonation sowed death on the beach and a column of black smoke rose above Vergarolla. 28 old depth mines had exploded, piled up long ago on the beach after having been cleared and detonators removed.” It was the men of the OZNA, as ascertained by the British secret services, who had reactivated the bombs the previous night. 116 were the dead. Among these were the two sons, aged 5 and 9, of the doctor Geppino Micheletti who, destroyed by pain, continued to operate anyway. He left Pula with the great exodus of 1947 because, he said, “I couldn't stand there and think I could cure my children's killers.” And, to accompany the memories of the exiles of Pula there is the continuous beating of the hammers, necessary to close the houses and the crates containing the household goods of the exiles.

On February 3, 1947, the first of ten voyages of the "Toscana" began, the steamer that brought about 20.000 refugees to Italy to the ports of Venice and Ancona. From here, with the railway convoys, these were directed to other areas of Italy where, however, not always, they were well received. In Bologna “The train was stoned by men waving the red flag with the hammer and sickle, others threw tomatoes, still others threw bread and pots with hot food on the ground. The milk for the children was spilled on the rails, the water was spilled and carried away. Meanwhile a loudspeaker croaked: We don't want the fascist train."

The exodus, which “it was really a plebiscite of Italianness”, had several waves: the first in 45-46, the last in 54-56. There were 117 refugee camps set up in Italy. “When the exile left, he tried to take away everything he could.” What was not collected over the years was kept in the port of Trieste. “In the 90s [...] the household goods were transferred and placed more rationally in Warehouse 18: two thousand cubic meters of 'stuff' that speaks and tells stories. For those who know how to listen. Simone Cristicchi listened to the voice of what he called 'the Spirit of household goods' and transferred it to his touching 'Magazzino 18', which was able to move the whole of Italy."

On February 10, 1947, the Peace Treaty was signed in Paris between Italy and the victorious nations of the Second World War, with which Pola and a large part of Istria, Fiume, Zara and the Adriatic islands were wrested from Italy, all delivered to Yugoslavia.

"The martyrdom of the sinkholes of Trieste and Istria, with their tragic burden of thousands of dead without a cross and the exodus of 350.000 Istrians, Fiume and Dalmatians have become the heritage of the common conscience of Italians since 2004 thanks to the law on Day of Remembrance, which is celebrated on February 10th every year. " The author of this book was its promoter.

Gianlorenzo Capano