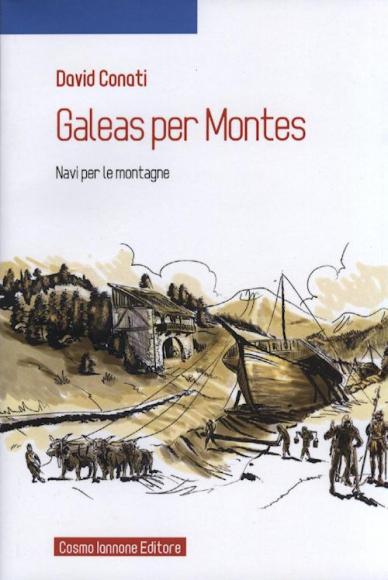

David Conati

Ed. Cosmo Iannone, Isernia 2019

Pag.272

Fitted into the historical novel genre, this book tells of an event that occurred between 1438 and 1440, when the Republic of Venice, which was expanding towards the mainland, encountered an obstacle in the Duchy of Milan, which was expanding towards the east.

The city of Brescia, a friend of Venice, was the cause of the clash as Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, decided to besiege it with the mercenary captain Niccolò Piccinino and Venice, with the mercenary captain Erasmo da Narni, better known as Gattamelata, he decided to free her.

The narrative voice is that of a boy, Menico who, employed by the squire Mercutio, followed the Gattamelata army. “Our enemy believes that the mountain route, between impervious gorges, with the risk of avalanches and boulders blocking the roads, is impracticable for an army like ours, accustomed to the great plains. […] Well, we will show him that he is wrong. We will go up the Ledro valley, we will go around the Garda or Benaco, if you prefer, from the north, we will pass through the Loppio valley and then descending through the Longarina valley we will reach the plain of Verona, where an army of the plain like ours will meet again at ease". This is the plan that Gattamelata explained to his staff and which was also listened to by Menico who entered the room, where the meeting was taking place, to bring some jugs.

On the night of 24 September 1438, having left Detesalvo Lupi to defend the city, an army of 4.000 men - of which Bartolomeo Colleoni was also part - under the command of Gattamelata, evading Piccino's surveillance, left Brescia with the intention of returning and free her, towards Verona.

Near the Sarca river there was a clash with Visconti's men. During the battle Menico lost consciousness and, when he woke up, he realized that he had lost his army with which, however, after a series of vicissitudes, he managed to reunite in Venice, where Gattamelata and Colleoni had asked the Maggior Consiglio, to finance a military undertaking which involved the construction of a fleet within a month. The Arsenal of Venice, on the other hand, was able to provide one ship a day, a fact which allowed the arsenalotti to be held in such high regard that they were the only non-noble people who did not have to kneel before the Doge.

“On the first days of January of the year of the Lord One thousand four hundred and thirty-nine, the Gattamelata flotilla commanded by Bartolomeo Colleoni is ready to set sail”: thirty-three boats in total went up the river, entering the Adige from its mouth, near Chioggia, until reaching Legnano and then Verona, while the bulk of the army followed the Gattamelata by land. The plan previously conceived by the latter was therefore put into action, namely to drag the fleet up the Trentino mountains until it reached northern Garda and then descend onto the plain in the direction of Brescia. To do this, the boats were pulled ashore and the hulls were then slid on wooden rollers called scalandroni.

“By dint of oxen, arms and rollers the ships reach the San Giovanni pass”. The climb, up to Mount Altissimo of Nago, lasted two weeks. For the descent, the sails were unfurled which, inflated by the wind, slowed the boats.

Near Torbole, on Lake Garda, in a small port quickly set up at the mouth of the Sarca, the entire flotilla was reassembled and armed. It was a very risky and very expensive undertaking, celebrated throughout Europe for the military engineering technique, which allowed supplies to be brought to the besieged Brescia.

“We are worthy of Hannibal and Scipio Africanus! – exclaimed Gattamelata when all the ships were brought down from the mountain”.

Gianlorenzo Capano