"In my book, On the edge of the foiba, I wanted to make a journey on the roots of Italianness in Istria, Fiume, Dalmazia and Venezia Giulia, precisely to make it clear that what is commemorated on February 10, Day of Remembrance, is a story that comes before the sinkholes and the exodus. This contrast of the Italians with the Slavic world was fueled above all by the Austrian empire, with the suicidal logic of the divide et impera, of which the Austrians themselves paid. So, everything that happens next, with the sinkholes and the exodus, in reality it is only the last stage of a very long journey that has its roots in a project, even expansionist, Slavic".

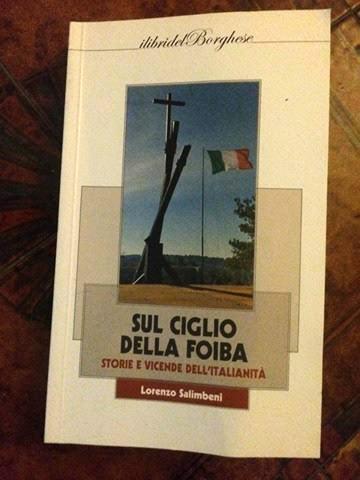

On the edge of the foiba. History and events of Italianness, The books of the Borghese publisher, is the first work by Lorenzo Salimbeni, a historian with various scientific publications behind him, a researcher at the National League of Trieste and the 10 February Committee and head of communications at the National Association of Venezia Giulia and Dalmatia. Triestino, class 1978, Salimbeni presented the work in Rome, at the Casa del Ricordo, together with Donatella Schürzel, president of the provincial committee of Anvgd and Giuseppe Parlato, professor of contemporary history at the University of International Studies in Rome. On the cover, the Foiba of Basovizza, a national monument.

You call the book On the edge of the foiba. And foiba means the communists titini, defenseless people slaughtered because they are Italian, the various treaties where Italy has actually sold its compatriots, the exiles treated by foreigners in their homeland and unpopular, the local left that still today minimizes or denies. It is a situation that after 70 years is not yet pacified. Perhaps because the exiles pay the price of having escaped from that paradise of real socialism that was communist Yugoslavia?

Yes, it is. In the 2017 the 70 years of the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty occur precisely and it is absurd to see how there are still problems open. Also because that peace treaty has united Italy and the eastern border with all those territorial transfers, but inside it had, also, some small guarantees to protect the property and rights of Italians. None of this has been respected, neither on the Yugoslav side nor, paradoxically, on the Italian side, if we think that even today the exiles are waiting for compensation from the Italian State which, with their property, abandoned in Istria, Dalmatia, Rijeka and who were nationalized by Yugoslavia, in fact our country has paid much of its war debt to Belgrade.

In the 1975, with the Treaty of Osimo, Italy could have claimed those territories. Instead he made further concessions to Yugoslavia ...

There was room for maneuver in the Treaty of Osimo. The Italian State did not want to understand that, having died Tito, Yugoslavia would have collapsed and agreed to sell what it could still claim against the former Zone B of the ever-established free territory of Trieste. The worst thing is that in Yugoslavia, dissolved around the nineties, there was not even the will to reopen the dispute with Slovenia and with Croatia. This is well explained by high-level jurists such as the professor of constitutional law Giuseppe De Vergottini: at least the question of Osimo could have been reopened, but it did not happen.

Instead the Italian State has preferred to pay the pension to some of the most famous Yugoslavian "infoibatori", Oskar Piskulich a name for all ...

Instead, we are still waiting for Italy to pay an acknowledgment to the Italian persecuted of the Tito regime as has been rightly granted to the persecuted anti-fascists or the deportees. Provisions are in their favor on the part of the Italian state and for a long time they have been asking equally for those who have suffered these things as Italians.

The Church, which however provided help in the reception, has always given the idea of being more in favor of the Slavic peoples and a little less on the side of the exiles. Is that so?

The problem is that, in the context of the eastern border, Italians, Slovenes and Croats represent a component of the strongly Catholic Slavic peoples and where even the same national element is born within the churches. Through preaching in Slovenian and Croatian, Slovenian and Croatian priests were, at the end of the nineteenth century, among the leaders of nascent Slavic nationalism and also of the Second World War. Many of them were also among Croatian collaborators, particularly among the Ustasha or even blessed the massacres carried out by Croatian nationalists at the expense of Orthodox Serbs, Jews and nomads. And yet, there were also Italian priests victims of the sinkholes, such as Don Angelo Tardicchio, parish priest of Villa di Rovino, taken at night by the Titini partisans and imprisoned in Pazin of Istria. He was killed and thrown into a bauxite quarry. When he was exhumed, it was seen that they had put a crown of thorns on his head, for further disfigurement. He is considered the first martyr of the sinkholes. Or, again, the Istrian Don Francesco Bonifacio, whose body has never been found, most likely thrown into a foiba. He too was beatified as a martyr for odium fidei. However, perhaps this lacked a more significant contribution from the center (Vatican, ed), certainly not from the territory. Suffice it to think, for example, of the bishop of Trieste and Capodistria Antonio Santin, who personally spent himself defending the city, to defend the population and later had a great role in the reception of refugees in Trieste.