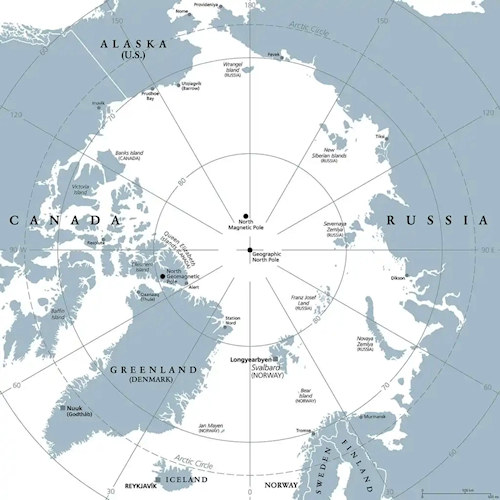

It will not constitute the maritime alternative to Suez and Malacca, at least for a few more years, but certainly there Northern Sea Route Arctic (NRS, 6000 miles, from the Barents Sea to the far eastern Bering Sea), with a dominant Russian presence (about 22 thousand km of polar coasts), is taking on more and more interest and space in the strategic and security debates of the United States, Canada and Europe. Its alternative role to the traditional hot routes, in particular Suez, which has now become incandescent with the Houthi missile attacks on merchant ships in the Red Sea, has in fact returned to the fore also in consideration of doctrinal statements and concrete actions that leave no doubt about the future plans of the two protagonists present and dominant in the region, namely Russia and China.

Hence the countermoves, especially from the United States, and the fear - already emerging in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with the end of the neutrality of the Scandinavian countries and the repercussions on the security of the entire northern European arc - that the Arctic exceptionalism, that is, being immune from open conflict over its control, has come to an end.

“There is no Arctic without Russia and Russia without the Arctic, and we will knock the teeth out of anyone who thinks they challenge our sovereignty” in fact, these were the words of Putin himself, in June 2022, the day after those of Biden according to whom “a war could break out over domination of the Arctic”1. And these squabbles, albeit routine, were followed by facts: in line with the Regaining Arctic Domination of 2021, Biden had already agreed to the allocation of one billion dollars in order to strengthen and consolidate new military bases in Alaska, while for the European Arctic the focus is on NATO enlargement to Sweden, after Finland has already entered be part of it last year.

Russia has various economic interests in the Arctic including oil and gas (estimated at 18 trillion dollars), fishing and minerals (30 trillion)2. The protection of extraction, processing and economic development of the region, evaluating possible risks of maritime, environmental and nuclear accidents, make Russia's military presence in the Arctic, and "in peacetime", a priority, on which however revolve at least two key military interests.

Russia has various economic interests in the Arctic including oil and gas (estimated at 18 trillion dollars), fishing and minerals (30 trillion)2. The protection of extraction, processing and economic development of the region, evaluating possible risks of maritime, environmental and nuclear accidents, make Russia's military presence in the Arctic, and "in peacetime", a priority, on which however revolve at least two key military interests.

First of all, the development and security of the Kola Peninsula are urgent for Moscow, located at the northwestern end of the territory of the Federation, as part of theregion' of Murmansk, the northern part of which is the only Russian region of Lapland. For some years now it has been the site of exercises for radar surveillance and communications activities, as well as for submarine warfare as it is the base for 7 of its 11 nuclear-powered submarines (SSBN) and armed with ICBM missiles. Practically the backbone of the Russian mobile nuclear deterrent. For this reason, for some years now, Moscow has launched projects to relaunch airport bases in Kola, a legacy of the USSR, of which 2 (Severomorsk-1 and Severomorsk-3) are already the main air bases of the Northern Fleet and used for Small and medium sized UAVs.

In the Kremlin's most optimistic forecasts, the development plan for Kola includes, by 2030, the construction of two new airports in Nagurskoye and Temp, for all types of aircraft of the Russian air and naval fleet, such as essential strategic and cargo bombers to logistical support for goods and weapons destined for other islands in the Russian Arctic. Furthermore, new landing strips are planned (Severomorsk-2, Severomorsk-3, Rogachevo, Talagi and Kipleovo), and the modernization of the former Safonovo plant, south of Severomorsk, right in the Kola Bay3. These are, therefore, strategic outposts that allow us to control the North-East Passage and the GIUK Gap (Greenland – Iceland – United Kingdom), the area that would see its value renewed in the containment strategic of Russian and now also Chinese commercial rivals but which, in the event of war, could prove to be one of the most important hubs for the navies of the region.

Then comes Moscow's interest, related to the first protect the entire range of its operational capabilities in the North Atlantic and the European Arctic in the event of conflict with NATO: its northern fleet, in fact, has direct access to the Barents and Norwegian seas, up to the Atlantic Ocean. It follows that Moscow's operational capabilities in Arctic waters are strategic and determining the outcome of a possible conflict on NATO's eastern flank.

But, in fact, it is not just Russia: because Beijing's maritime ambitions - considering that 90% of Chinese goods travel by sea and China-Europe maritime trade is three times greater than air trade - extend beyond the seas warm oceans and aim to have access and influence in the Arctic, in shared control with Moscow.

But, in fact, it is not just Russia: because Beijing's maritime ambitions - considering that 90% of Chinese goods travel by sea and China-Europe maritime trade is three times greater than air trade - extend beyond the seas warm oceans and aim to have access and influence in the Arctic, in shared control with Moscow.

The data speak for themselves: from 18 million tons of all goods sailing those icy waters in 2018, it is hypothesized (Russian sources) that they will rise to 90 million in 2024 up to 100 by 2030, while others (US sources) speak of a more modest 35-40 million .

China, trying to position itself competitively in world trade, is focusing on the NRS, shorter (an estimate of 13 thousand km compared to 21 thousand), and currently safer than the traditional routes to the south (Malacca and especially Suez), now also accessible due to the gradual melting of the ice. Hence, the intention to increase its infrastructure in the polar region, consequently also strengthening its defense activities.

All of this is part of the Chinese belief that the 21st century is the "century of oceans", recognizing the importance of sea routes in its development strategy, and also because it is a "nation close to the Arctic"4, hence their defense, as already outlined in the 2018 White Paper, which highlighted Beijing's political aims regarding the Arctic, such as "protect, develop and participate in its regional governance"5. And precisely with a view to defense, "and in compliance with international law", the joint military exercises of Russia and China took place in the Arctic waters and skies in August 2023, with 11 warships which, having set sail from the Sea of Japan, crossed the Bering Strait and passed off the coast of the Aleutian Islands, opposite Alaska6. A deployment of forces that alerted the US Department of Defense's Arctic Defense office, which showed concerns about "increasing levels of investment in (Russian and Chinese) military capabilities in the Arctic region"7.

In recent weeks, these fears have been fueling rumors of a US reset on DOD policies in the region, including changes in the way it trains and equips its forces, requiring it to rethink everything from an operational perspective in Arctic waters. Elements of change that will be outlined, according to sources from the US Arctic Defense office, in the publication by the end of January regarding the DOD's global strategy. Hence the renewed interest and alertness of military security analysts. Not only more regular and joint exercises with NATO forces, like those last November in the Baltic Sea, led by Finland8, but also further increases in federal budgets (already 200 million dollars in 2023) for the modernization of military infrastructure in Alaska (old and heavily corroded).

In recent weeks, these fears have been fueling rumors of a US reset on DOD policies in the region, including changes in the way it trains and equips its forces, requiring it to rethink everything from an operational perspective in Arctic waters. Elements of change that will be outlined, according to sources from the US Arctic Defense office, in the publication by the end of January regarding the DOD's global strategy. Hence the renewed interest and alertness of military security analysts. Not only more regular and joint exercises with NATO forces, like those last November in the Baltic Sea, led by Finland8, but also further increases in federal budgets (already 200 million dollars in 2023) for the modernization of military infrastructure in Alaska (old and heavily corroded).

But in recent weeks something else has been decided in the US which has agitated Moscow.

The State Department's statement is from the end of December 2023 new geographic coordinates to define the boundaries of the continental shelf of the United States: in practice, one million square kilometers distributed in seven regions which, years of research, scientific missions and detailed mapping, have contributed to proving as US territory9. In short, an area, above and below their already extensive continental shelf, including the Arctic, the size of two Californias, which the United States claims as its own on the basis of international law and the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (which however, the United States has not yet ratified), because it is for the protection and management of vital resources and habitats. In this way, Washington seeks to preserve mineral reserves crucial for the development of its future technologies. This expansion, particularly in the Arctic region, has the potential to trigger conflicts over its possession and control, and is supported by a determination by the United States, as resolute as that of China for the South China Sea and certainly no less than the Russian one for most of "its" seabed, from the Bering Sea to the Arctic.

The Russian response was, and could not have been otherwise, dry and immediate: in addition to being "unacceptable", it was stated that “we have taken and will continue to take all necessary measures for our national interests in this geographical area”10. In short, while waiting for the new DOD document at the end of the month, the start is decidedly open, on all fronts, even the cold and inhospitable one of the great white expanse of the North Pole.

1 On the role of the Arctic in Russian political and military thought, see G. Tappero Merlo, NATO-Russia, a global clash over the Arctic, “The Glass Door” 29 January 2023, https://www.laportadivetro.com/post/l-editoriale-della-domenica-nato-rus...it's-global-clash-for-the-arctic

9 For a graphical view, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P5506Qq0pRs

10 https://www.aa.com.tr/en/americas/us-broadens-maritime-territories-into-...

Images: MoD Russian Fed. / U.S. DoD / MoD China / U.S. Army