The relations between the Italian and French High Commands, during the Great War, constituted the first example of military collaboration between the two nations by the 2 ° War for Italian Independence, which ended with the Armistice of Villafranca of 12 July 1859.

It is also true that, apart from the strong contrasts on the conduct of military operations that distinguished it, the relationship established between the Italian Supreme Command and theHaut Commandement transalpine was always characterized by clarity of intent and undoubted loyalty. Although it could not build neither the synergy of efforts nor the convergence of the war strategies that many - more in Rome than in Paris - had hoped, nevertheless the collaboration between the two nations succeeded in realizing the common objective of the defeat of the Central Empires.

The 24 may 1915 the Kingdom of Italy entered the war alongside the powers of the Entente (Great Britain, France and the Russian Empire) against the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Salandra government, when the conflict broke out on the European continent and the main Powers declared each other war, had officially chosen the path of neutrality (2 August 1914), despite the treaty of the Triple Alliance - to which the Kingdom of Italy he had joined the 1882 and renewed in the 1912 - he still formally linked it to his Austrian and German allies.

However, the treaty did not provide for the automatic entry into the war of one of the signatory Powers, in the case of an attack triggered by the others and, in any case, prior consultations between the allies should have preceded any eventuality of this kind. In reality, Germany had violated Belgian neutrality by attacking the northern regions of France; following the arrest of the Russian offensive, in East Prussia, with the battle of Tannenberg and the Masuri Lakes (August-September 1914) it had switched to the counter-offensive in Poland. Austria-Hungary in turn, with great difficulty, had defeated the Serbian Army forcing it to a hasty retreat on the Albanian coast, only to be saved, in December of 1914, by the Italian Navy. Neither of the two Powers had bothered to warn the Italian ally in time of their intentions, demonstrating once again the usual disregard for what was, in its own right, the minor Power - and Latin - of the Triple Alliance.

The Government of Rome therefore considered itself free from the commitments made in the past and refrained from taking part in the conflict, thereby provoking the bitterness of the Austro-Germans, who would later accuse the Kingdom of Italy of treason, and at the same time mixed attitude of hope and suspicion by the Entente Powers.

The Government of Rome therefore considered itself free from the commitments made in the past and refrained from taking part in the conflict, thereby provoking the bitterness of the Austro-Germans, who would later accuse the Kingdom of Italy of treason, and at the same time mixed attitude of hope and suspicion by the Entente Powers.

We must also underline the loyal behavior that Italy held towards France in the course of those feverish moments, especially bearing in mind the tensions that had characterized the Italian-French relations from 1870 to 1915, in Europe as in North Africa: the claims on Alps, frictions in Tunisia, Ethiopia and Libya.

There is no doubt that at the end of the nineteenth century, the young Kingdom of Italy felt threatened by the transalpine expansionist policy. The adherence to the Triple Alliance had been a precaution precisely in order to protect itself from a possible French attack. In fact, a conflict with its neighbor on the West side of the Alps was believed at the beginning of the twentieth century, both by the Government and by the Italian General Staff, much more likely than one with the Habsburg monarchy, with which there was still the serious problem of unredeemed lands.

Despite this, the Kingdom of Italy did not take advantage of the situation to launch a surprise attack against Paris and remained respectful of the agreements signed with the French government starting from 1902 (Prinetti-Barrère agreements), according to which the two countries reciprocally not to participate in a war of aggression directed against the other.

It is therefore clear that a different behavior on the Italian side could have had disastrous consequences for Paris, preventing the French army, in the summer of 1914, to concentrate all its forces in the decisive battle of arrest on the Marne river.

Following political, strategic and military evaluations following the progress of the conflict, but also the sympathies for French democracy and the reaction of Italian public opinion to the German aggression of Belgium, induced the Government of Rome to join the Intesa.

On the French side, the entry into the war of the kingdom of Italy had fueled not a few hopes of a rapid solution to the conflict. In fact, the transalpine High Command, while trying in vain to break through on the western front - Joffre's offensive in Artois in May 1915 and in Champagne in the following September - believed possible a great joint offensive of the Italian and Serbian armies on Trieste, and subsequently on Budapest and Vienna, in conjunction with a decisive Russian advance in the Carpathian and Eastern Alps region.

On the French side, the entry into the war of the kingdom of Italy had fueled not a few hopes of a rapid solution to the conflict. In fact, the transalpine High Command, while trying in vain to break through on the western front - Joffre's offensive in Artois in May 1915 and in Champagne in the following September - believed possible a great joint offensive of the Italian and Serbian armies on Trieste, and subsequently on Budapest and Vienna, in conjunction with a decisive Russian advance in the Carpathian and Eastern Alps region.

It was a strategic vision, however, that was not based on a sufficiently detailed examination of the situation on the Italian front. Accustomed to the operations conducted on the wide plains of northern France, where very soon, however, after an initial phase of movement, the barrage of large-caliber artillery, artificial obstacles and substantial equivalence in the number of opposing armies had transformed the maneuver in position warfare, the French High Command had not well considered the difficulties represented by the terrain on which the Italian armies would have to conduct their attacks, namely the Alpine arc, the region of the Altipiani and the Karst. All places characterized by a complex orography, with the dominant heights occupied by the Austro-Hungarian troops, who had previously had the time to reinforce them with the construction of trenches and camp fortifications. Moreover, the trend of the front line, in the shape of an arch and with the concavity occupied by Italian forces, made it particularly vulnerable to an Austrian counter-offensive from Trentino which, breaking into the area between Vicenza and Padua, would have risked encircling the troops 'Isonzo.

The immobilization of the Italian front, after the summer of 1915, as well as the failure of the Russian offensive in Galicia, which was added to the collapse of Serbia in the autumn, helped to change the initial optimism, soon convincing the French High Command that no truly decisive result would have been obtained on the Italian theater of operations. Even the periodic reports of military observers sent on the Italian front, substantially negative for what concerned organization, equipment and morale of the troops, increased the distrust of the French General Staff against the Italian one regarding the possibility of planning effective offensives. All this fueled by the persistent transalpine prevention towards everything that has the defect of coming from the Italian side of the Alps.

In June of the 1916, despite the Austro-Hungarian offensive on the Altipiani - the Strafexpedition (Punitive shipping) - had been brilliantly arrested, from the earliest stages, by the Italian troops, who later forced the enemy to retreat to his starting positions, Joffre remained anchored to his conviction that the Italian was only a secondary front and therefore it was not worthwhile to send French armies to reinforce it. Not even the resumption of the Italian offensive in August, which would have allowed the occupation of the city of Gorizia (VI Battle of the Isonzo), served to make the French High Command change its mind, inclined only to support the Russian ally and , to a lesser extent, the Romanian one.

In June of the 1916, despite the Austro-Hungarian offensive on the Altipiani - the Strafexpedition (Punitive shipping) - had been brilliantly arrested, from the earliest stages, by the Italian troops, who later forced the enemy to retreat to his starting positions, Joffre remained anchored to his conviction that the Italian was only a secondary front and therefore it was not worthwhile to send French armies to reinforce it. Not even the resumption of the Italian offensive in August, which would have allowed the occupation of the city of Gorizia (VI Battle of the Isonzo), served to make the French High Command change its mind, inclined only to support the Russian ally and , to a lesser extent, the Romanian one.

The Czarist Army, which would have collapsed the following year, received the 1916 equipment supplied by France in the 897. Those promised to Italy, which would never have failed to its commitments, were not that 60, and all supplied with the dropper. The aid sent to Romania had no better luck, given that this, not even four months after its entry into the war alongside the Entente (27 August 1916), was defeated by the lightning-fast German and occupied in almost the entirety of its territory, forced to surrender in the following March. Even the supply of large calibers to the Italian artillery, despite the obvious shortcomings, was only symbolic in the 1915, despite repeated requests sent to Paris by General Luigi Cadorna. Still the following year, the sending of 60 field cannons from 120 / 25 on the Italian front was characterized by long polemics between the Government of Paris and General Joffre, who categorically opposed that they were moved from the artillery park of his front.

Cooperation had not encountered less difficulties in the naval field. At the end of the 1916, when the threat of a German invasion of France through Switzerland appeared more real than in the past, the possibility of establishing a continuous front from the Channel to the Adriatic was taken into account by both Joffre and Petain and Foch , the latter author of the plan to cope with the danger (plan H). Consequently, the consideration of the French High Command regarding the Italian front changed slightly. The prospect of sending 2-4 divisions to Italy - sufficient, according to the opinion diffused in the transalpine military environments, to give back confidence to the Italians - was taken into account by Nivelle, who took over 12 December 1916 in Joffre as commander in chief of the Armies of the North and Northeast. The project, however, was quickly discarded.

Cooperation had not encountered less difficulties in the naval field. At the end of the 1916, when the threat of a German invasion of France through Switzerland appeared more real than in the past, the possibility of establishing a continuous front from the Channel to the Adriatic was taken into account by both Joffre and Petain and Foch , the latter author of the plan to cope with the danger (plan H). Consequently, the consideration of the French High Command regarding the Italian front changed slightly. The prospect of sending 2-4 divisions to Italy - sufficient, according to the opinion diffused in the transalpine military environments, to give back confidence to the Italians - was taken into account by Nivelle, who took over 12 December 1916 in Joffre as commander in chief of the Armies of the North and Northeast. The project, however, was quickly discarded.

At the 6 1917 January inter-city conference in Rome and ten days later in London, Nivelle firmly opposed Lloyd George's proposal to plan a major Allied offensive on the Isonzo. It is probable that, behind the French refusal, there was a will to give absolute priority to the next offensive in preparation on the western front, in the region of Chemin des Dames (9-19 April 1917), which, in the intentions of Nivelle, would have to inflict a decisive defeat for the German forces. It would have instead resulted in a colossal fiasco, one of the most sensational failures of the entire conflict for the French and British, which led, among others, to the definitive dismissal of the commander in chief transalpine.

Despite this, the French interest in the Italian front continued to remain lukewarm and a change of strategy in the conduct of the war, with the consequent shift of the war effort from the western to the southern front, was almost never taken into consideration by the transalpine strategists. The idea that the Germanic territory could be invaded via Vienna, thus concentrating the attacks on the weaker of the two Central Empires, always remained foreign to the military mentality beyond the Alps, totally focused on direct confrontation with Germany in the North and East. ; second floors, in the perspective of revenge, had been conceived and repeatedly reworked in order to resume what had been lost with the burning defeat of the 1870: Alsace and Lorraine.

The 15 May 1917, following the torch of Nivelle, General Philippe Pétain became the commander in chief of the French Armies of the North and North-East, practically of the entire French Army.

The 15 May 1917, following the torch of Nivelle, General Philippe Pétain became the commander in chief of the French Armies of the North and North-East, practically of the entire French Army.

Petain, who was one of the best commanders of the Great War, was one of the few who did not look at the events of the Italian front with disinterest typical of his predecessors. Although he was convinced of the lack of preparation of the Italian army at the time of entry into the war, he often had words of sincere admiration for the heroism and spirit of sacrifice shown by Italian troops throughout the conflict and he repeatedly recognized the importance of the Italian war contribution to the common effort of the Entente.

Also the strategic vision of the operations to be conducted in the ongoing conflict was decidedly more extensive in Petain than in the other French military leaders of the time. Convinced of his strategic plan to move the axis of the war from Champagne and Flanders, where it had been held up to now, to the Alsace of the North, in anticipation of reaching objectives in the regions of the Rhine and the Danube, Petain had planned four possible battles for the coalition of the Entente: one of rupture, French, in Upper Alsace; a Franco-American in Lorraine; a Franco-British in Picardy and a French-Italian in Northern Italy. In his view of the war, therefore, the Italian front was closely linked to the operations that would be carried out on the North-East front.

The following 25 June took place in Jean-de-Maurienne a bilateral meeting between Foch and Cadorna. The latter complained about the already known shortcomings of his army on the artillery - the Italian Army needed at least 180 batteries - a lack of which the Austrians could have benefited. The requests of the Italian Chief of Staff fell again into the void, on the other hand Foch was profuse in many exhortations to continue the offensive efforts, considering now the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of the forces. Also, three days later, in a conversation with General Robertson, Chief of Staff of the British Army, Foch once again expressed the futility of sending French troops to the Italian front.

Therefore, the Italian Supreme Command had to rely once again on its own strength, starting from 10 in August 1917 launched yet another offensive against the Austrian lines (XI battle of the Isonzo). The attack managed to break them in several points on the Bainsizza plateau, forcing the enemy forces to retreat for a few tens of kilometers, but not to obtain a decisive victory.

Therefore, the Italian Supreme Command had to rely once again on its own strength, starting from 10 in August 1917 launched yet another offensive against the Austrian lines (XI battle of the Isonzo). The attack managed to break them in several points on the Bainsizza plateau, forcing the enemy forces to retreat for a few tens of kilometers, but not to obtain a decisive victory.

On the Italian side, instead, the French request was accepted to send a first contingent of 5.000 militarized workers (TAIF, Italian Auxiliary Troops in France) on the other side of the Alps, to be employed in the French armaments industry, in the construction of railways and in setting up a third defensive position in Lorraine. An aspect little known by the official historiography, especially from the transalpine one, but which proved to be decisive - at the end of the conflict the Italian workers in France will be 136.000 - for the victory of the Entente Powers on the western front.

The turning point is 24 October 1917, when the Austro-Hungarians, with the help of 7 German divisions, carry out a massive attack between the Tolmino and the Plezzo, in the region of Caporetto (XII battle of the Isonzo).

It was only then, fearing that the Austro-German troops could spread into the Po Valley and reach up to Milan, if not to Genoa, that the French and the British decided to intervene directly on the Italian front. Their expedition, consisting of 11 divisions, of which 6 French and British 5, was deployed in the Po Valley between October 31 and the end of November, nevertheless was able to conduct some truly decisive action, since already the 6 November the Italian Army had succeeded, by itself, to definitively arrest the advance of the enemy on the Piave and on the Grappa.

Without having to return to the endless controversies that arose at the end of the conflict about the attribution of this victory, which the French and English did not hesitate to attribute to their presence in Italy, it will be sufficient to report the calm admission of Marshal Petain, in the speech of entry on the occasion of his admission among the Immortals of the French Academy on 23 January 1931: the enemy had already been stopped on the banks of the Piave, before it was necessary to engage our divisions.

Without having to return to the endless controversies that arose at the end of the conflict about the attribution of this victory, which the French and English did not hesitate to attribute to their presence in Italy, it will be sufficient to report the calm admission of Marshal Petain, in the speech of entry on the occasion of his admission among the Immortals of the French Academy on 23 January 1931: the enemy had already been stopped on the banks of the Piave, before it was necessary to engage our divisions.

To further increase the tension contributed, the November 5, the Italian request, formulated by General Porro, that the French Shipping Corps in Italy were under the command of the Supreme Command, which would have used it in the ways and times that it deemed most appropriate. Request that, of course, both Foche and Petain, they agreed not to even take it into consideration.

At the inter-allied Rapallo Conference, from the 5 to the 7 November 1917, Prime Ministers Lloyd George and Painlevé forehead of Cadorna in exchange for aid to the Italian army. Their political vision was fully supported by their military leaders, who, in their reports on the situation on the Italian front, had spoken of a real panic which, according to them, after the Austro-German breakthrough, also involved the Supreme Command. It was in reality an unjust and obviously false judgment. Cadorna had committed, during his command, the same errors that had caused, in the 1915 and 1916, the definitive torpedoes of Joffre and Nivelle. Above all the obstinacy in expensive offensive in men and means, but not very profitable on the tactical level, which in the long run had exhausted the army and brought down the morale of the fighters.

However, albeit with all the shadows of his work, Cadorna was able to keep himself always very lucid and active, even during the dramatic hours of retreat and it is also undeniable that his work as head of the Staff is to plan the victorious resistance on the line Piave, who would have permanently blocked the enemy's advance and threw the premises for the final victory.

In any case, relations with the other powers of the Entente had to be preserved and the King and the Italian Government agreed to replace him with the general Armando Diaz.

In any case, relations with the other powers of the Entente had to be preserved and the King and the Italian Government agreed to replace him with the general Armando Diaz.

However, that of the future Duke of Victory was a choice which, if it proved to be extremely positive for the Italian Army, was also counterproductive for the Allies. Diaz, in fact, contrary to Cadorna, always showed little inclination to accept the requests of the other military leaders of the Entente and to subordinate his action of command to the global interests of the other Powers.

After the Caporetto crisis, the interest of Paris for the Italian front quickly began to decline. Hence the concern of the Transalpine High Command to recall as soon as possible the French troops that still found there - at least the two Divisions of the XII Army Corps - that was insistently requested by Pétain to Clemenceau starting from 14 January 1918, as soon as it became clear that the Austro-German offensive capacities, on the Piave line, had been frustrated. However, the French prime minister was opposed to this request, fearing retaliation for the interruption of the flow of militarized workers to France, so this withdrawal did not begin but starting from 24 March 1918, faced with the emergency arising from the new German offensive on the western front in the San Quintino region and the consequent breakthrough of the sector held by the British. The only French forces remaining in Italy until the end of the war were the XXIII and the XXIV Infantry Division.

Starting from 15 April 1918, moreover, in order to balance the French aid to Italy, the Supreme Command consented to send the II Army Corps commanded by General Albricci, formed by two Divisions plus support departments, to fight on the western front, in the Champagne.

The Great Unity would participate, among others, in the great defensive battle of 15 July 1918 (The Battle of the Marne), which permanently blocked the remaining German hopes of quickly resolving the war and took part in the Allied offensive of the following September against the salient of Laon. The November 11 Armistice took the Italian troops in full swing, over 90 km from their starting lines, in front of the historic town of Rocroi, on the Meuse, which was liberated by the 19 ° Infantry Regiment of the Brescia Brigade.

28 March 1918 Foch, following the Interallied Conference of Doullens, was named Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces. Following this event, relations between the Italian Supreme Command and the Interallied Headquarters became prominent compared to those with the French High Command.

It is interesting to note that the most relevant aspect of this period of the war was the insistence shown by Foch for Diaz to quickly resume the offensive on the Piave. However, the opposition of the Italian Chief of Staff to this solicitation, considered to be premature, was based on a very thorough examination of both the military situation of the Italian forces and that of the Austro-Hungarians. In fact, following the breakthrough of Caporetto, the Italian forces had reduced from 61 to 37 divisions, moreover a huge quantity of artillery pieces had been lost.

This situation took time to be remedied, it was essential to replace the losses of material and to provide both the incorporation and training of new classes called to arms, including that of 1899. Moreover, Diaz was perfectly aware that time played in his favor, due to the slow but inexorable political-military decline of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which could not but have a devastating effect on the operational capacity of its Army. This had suffered a series of heavy defeats on the Piave, Grappa and Montello, in June of 1918, because of the relentless resistance - almost desperate - exerted everywhere by Italian soldiers (battle of the Solstice) and began to show signs of disruption to following the increasingly strong autonomy ambitions of oppressed minorities.

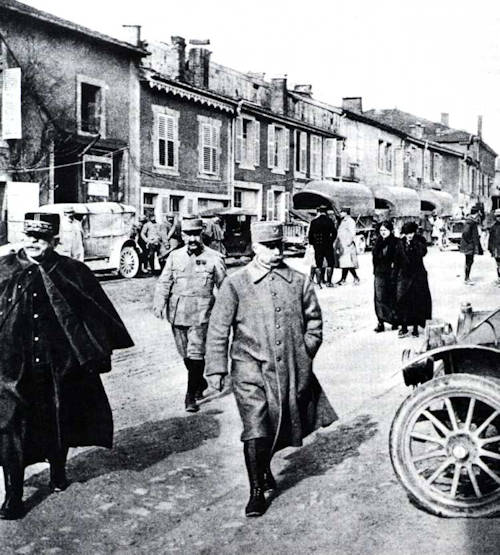

It is also interesting to note how, despite the French military personnel posted in Padua at the Supreme Command, they communicated that the Italian Army was not yet ready to launch a large-scale offensive, Foch (pictured, right) remained firm in his request of an immediate attack on the Piave.

It is also interesting to note how, despite the French military personnel posted in Padua at the Supreme Command, they communicated that the Italian Army was not yet ready to launch a large-scale offensive, Foch (pictured, right) remained firm in his request of an immediate attack on the Piave.

However, when Diaz asked him in the summer of 1918 the support of a dozen allied divisions with which to set up the necessary reserve for the much-demanded offensive, he again expressed a refusal. That was renewed when, a short time later, the Supreme Command asked that the sending of US troops into Europe was also extended to the Italian front. The answer was an infantry regiment and some ambulances: here is the totality of American support that was sent to Italy.

It should therefore not be surprising if Diaz, supported by the president of the board Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (second from left in the opening photo), proved to be very resistant to submitting to the directives of the Interallied War Committee, claiming that autonomy of conduct Italian front that the French, after so much disregard for it, did not seem now more willing to accept. On the other hand, the influence of Foch, which the 7 August 1918 had received the Marshal's staff, formally did not extend to the Italian front.

So, when Diaz unleashed the final offensive of Vittorio Veneto, the 24 October 1918, which would have routed the enemy troops and led to victory, the forces he could dispose of were still inferior to those of the Austro-Hungarian army: 57 divisions, of which 51 Italian, 3 British, 2 French and a Czechoslovak against 60 fielded by the enemy.

The scope of this battle - the only spectacularly decisive one in a four-year war, according to the opinion of the transalpine historian Henry Contamine - was unjustly underestimated by both Foch and the other French military chiefs, convinced by reports sent by General Julian of Padua that they asserted that the Austro-Hungarian armies had withdrawn without putting any resistance. This does not explain, however, the heavy losses suffered by the Italian army during the last months of the war (36.498 between dead and wounded), caused by an enemy resistance that was, as always, fierce and determined.

After the unconditional surrender of the Habsburg Empire (4 November 1918), with the Italian troops launched in the direction of Innsbruck, it was probably the threat of an Italian offensive conducted from the south, through the Tyrol and Bavaria, whose planning was underway at the Supreme Command, which forced Germany to abandon a fight that otherwise could have successfully led at least until the spring of 1919. The consequences would have been negative especially for France, with still a large part of its occupied territory and systematically devastated by the enemy.

It is also true that, without the battle of Vittorio Veneto and the consequent Italian-Austrian armistice of the November 4, with the cession to Italy of all intact Austrian railways and therefore with the real possibility of an attack on German territory through Tyrol, Berlin it would not have, already the November 5, issued the precipitous retreat that six days later would have led to the surrender of Germany.

It is also true that, without the battle of Vittorio Veneto and the consequent Italian-Austrian armistice of the November 4, with the cession to Italy of all intact Austrian railways and therefore with the real possibility of an attack on German territory through Tyrol, Berlin it would not have, already the November 5, issued the precipitous retreat that six days later would have led to the surrender of Germany.

It is clear from what has been written up to now that, during the Great War, the Italian and French strategic plans met only occasionally. Above all because the Italian front was always considered by the High Transalpine Command as secondary, whose only interest was that it did not collapse. Even the scant consideration in which the French military leaders held the Italian ones certainly did not help to facilitate the integration of this front, which experienced a temporary interest only during the crisis generated by the break-up of Caporetto.

Moreover, the conflict of jurisdiction that caused strong contrasts, between Foch and Petain, for the command of the French Corps of Expedition in Italy aggravated the situation, increasing the suspicions and the discontent of the Italians.

General Diaz, who became the new Chief of Staff of the Italian Army in November 1917, was able to profit from this situation. He led the war with an autonomy of action that made its subordination to the supreme inter-allied chief, Marshal Foch, completely formal, and made the Italian Army the least integrated into the command system of the Entente.

(photo: web)