Western military history books are full of heroic battles won, but they often tend to put less emphasis on defeats. Especially those of the last two centuries, in which the concept of Euro-American military superiority is taken for granted. Yet things didn't always go well for the thundering imperial war machines of the 27th and 1880th centuries. The battle of Maiwand, fought in the context of the second Anglo-Afghan war on XNUMX July XNUMX between the Anglo-Indian and Afghan armies, is undoubtedly one of the most striking cases. It was in fact the only big one debacle of the Anglo-Saxon Empire, along with that of Isandlwana, against a non-western people in modern times.

Little known in the United Kingdom itself, the battle of Maiwand is instead well rooted in the memories of the Afghans who still consider it one of the founding moments of their history and national identity. Leading the Afghan army was the governor of the province of Herat, Ayub Khan, who, driven by the dual objective of chasing foreign invaders from their land and conquering Afghanistan itself, decided to march to the capital, passing through the southern city of Kandahar. Having learned of Ayub's plan, the British military leaders, who were already organizing the retreat after the installation of Abdur Rahman as the new emir in Kabul, instructed General George Burrows to end the "revolt" and conclude once and for all , the war in the Asian country.

Despite the overall superiority of the British military instrument, in this case the Anglo-Indian army found itself fighting at a marked disadvantage, mainly due to its numerical inferiority. In fact, it has been calculated that the Burrows contingent numbered just over 1500 men, 350 cavalrymen and about ten artillery pieces, against Ayub's over 10 soldiers, 000 cavalry and more than 3000 artillery pieces. However, if numerical inferiority has undoubtedly played an important role, its importance should not be overestimated. For the European armies of the time, it was normal to fight with numerically superior forces, but qualitatively and technologically inferior. In the Afghan case, however, the British clashed against a well-trained army equipped with artillery of the same level. In turn, the Anglo-Indian soldiers who fought in Maiwand were mainly new recruits and not yet fully accustomed to the harsh climatic conditions of Central Asia. Lack of water, tropical diseases and unbearable temperatures were constant elements for British soldiers employed in those regions.

Despite the overall superiority of the British military instrument, in this case the Anglo-Indian army found itself fighting at a marked disadvantage, mainly due to its numerical inferiority. In fact, it has been calculated that the Burrows contingent numbered just over 1500 men, 350 cavalrymen and about ten artillery pieces, against Ayub's over 10 soldiers, 000 cavalry and more than 3000 artillery pieces. However, if numerical inferiority has undoubtedly played an important role, its importance should not be overestimated. For the European armies of the time, it was normal to fight with numerically superior forces, but qualitatively and technologically inferior. In the Afghan case, however, the British clashed against a well-trained army equipped with artillery of the same level. In turn, the Anglo-Indian soldiers who fought in Maiwand were mainly new recruits and not yet fully accustomed to the harsh climatic conditions of Central Asia. Lack of water, tropical diseases and unbearable temperatures were constant elements for British soldiers employed in those regions.

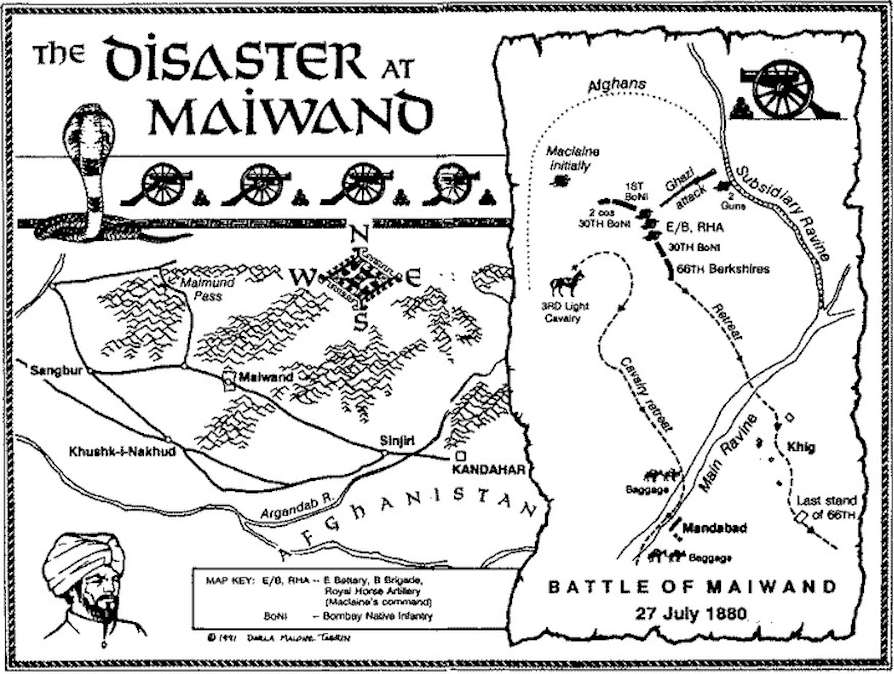

At the time of the battle, the two parties immediately engaged a clash with their respective artillery, in which the Afghan country surprisingly prevailed. This, in fact, did not only possess more pieces of artillery, but also managed to get hold of some of the best western cannons, such as Armstrong, built in England. He followed the advancement of the Anglo-Indian Infantry, but he was soon surrounded by the many Afghan forces who, using their number and knowledge of the territory, surrounded the enemy, forcing him into defensive positions and ultimately a disastrous retreat. At the expense of over 1500 men, compared to the Anglo-Indian 900 victims, Ayub had gained a historic victory, and could now besiege Kandahar, in which he had been sheltering the rest of General Burrows's troops, awaiting receiving reinforcements .

If, on a strategic level, Maiwand's defeat did not alter the outcome of the Anglo-Afghan War, it still had a strong symbolic and psychological impact, both in Great Britain and Afghanistan itself. For the Afghans, as already mentioned, the battle was a ransom moment and contributed to the creation of a national identity sentiment, founded on the unity and the courage of the Afghans, as opposed to the outer invader.

If, on a strategic level, Maiwand's defeat did not alter the outcome of the Anglo-Afghan War, it still had a strong symbolic and psychological impact, both in Great Britain and Afghanistan itself. For the Afghans, as already mentioned, the battle was a ransom moment and contributed to the creation of a national identity sentiment, founded on the unity and the courage of the Afghans, as opposed to the outer invader.

Unlike in the United Kingdom, the outcome of the battle was welcomed with a mixture of anger, amazement and regret. In fact, the XIX century represents the apogee of the economic, military and political power of the British Empire. A defeat against a people considered inferior was not contemplative. It was also feared that what could have helped the British RAJs in the Indian subcontinent to rebel themselves as they had done in the 1857. The same Queen Vittoria wrote that she was "in a state of deep anxiety." However, the subsequent expedition of General Roberts and the subsequent defeat of Ayub in the Battle of Kandahar helped partly to obliterate the battle of Maiwand and redeem British imperial honor.

(photo: web)