The Great War takes on a fundamental role in the history of Italy, since it was the first real difficulty faced by the whole nation after unification, contributing to the newborn and fragile national identity. In fact, the masses of men in the various military departments, coming from social classes and different places, created the conditions for soldiers to share their regional culture with other soldiers, laying the foundations for a more rooted national conscience.

Italy fought the first world conflict mainly on the East Alps against the Hapsburg Empire, which was also called "White War" referring to the snowy summits of the area. It was a clash characterized by a war of position, in uniformity with the other fronts in Europe, which underwent very few territorial changes in the first years of the conflict (1915-1916).

The wind began to change in the 1917. With the failure of the "Strafexpedition" carried out by the Austrians at the end of 1916 and the last two Italian offensives in the 1917 (tenth and eleventh battle of the Soon), it was necessary for both the Italians and the Austrians, producing offenses that could move the static Alpine face.

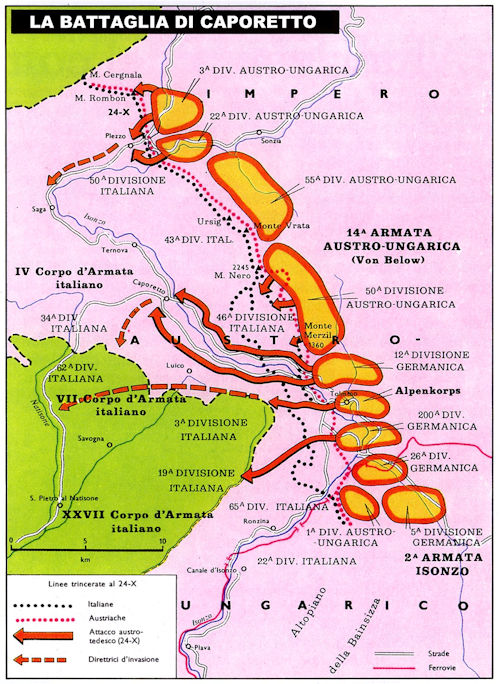

Austria-Hungary therefore received men and means of support from the German ally, began preparations for an attack aimed at regaining the territories of Trentino (conquered by the Italians in the 1916) and breaking down the enemy lines to provoke a collapse of the Royal Italian Army. A plan was prepared that was based on 3 main directions: an army group would have aimed at the Alto Tagliamento, breaking in Piezzo near Caporetto; another would attempt to occupy the Colovrat mountain range; while the last group of armies would have attempted a massive assault on the defensive lines that kept the area near Cividale del Friuli, breaking into Tolmin with the aim of taking control of it.

Austria-Hungary therefore received men and means of support from the German ally, began preparations for an attack aimed at regaining the territories of Trentino (conquered by the Italians in the 1916) and breaking down the enemy lines to provoke a collapse of the Royal Italian Army. A plan was prepared that was based on 3 main directions: an army group would have aimed at the Alto Tagliamento, breaking in Piezzo near Caporetto; another would attempt to occupy the Colovrat mountain range; while the last group of armies would have attempted a massive assault on the defensive lines that kept the area near Cividale del Friuli, breaking into Tolmin with the aim of taking control of it.

According to some sources, the general of the Italian General Staff Luigi Cadorna (photo), was aware of the massing of troops and enemy battle plans. In light of this, we will talk about how the Battle of Caporetto could be considered not a defeat - as has always been defined - but as a strategic retreat and a situation already envisaged by Cadorna (thesis supported by Titian Berté, author of the essay "Caporetto: victory or defeat?" and editor of the Museo Storico Nazionale della guerra in Rovereto).

The 23 October, in fact, Cadorna wrote to the Italian War Minister that "the offensive should be developed [...] with the preponderance of effort between the Plezzo basin and the bridge head of Tolmin." Of course, the general was not aware of the tactics that he would use the Hapsburg Army the next day, such as bombing with toxic gas and the use of assailants organized on the German model, but he certainly managed to predict with mechanical precision the early stages of the battle. The 24 October 1917 Austro-Hungarians launched their massive offensive on the Italian lines. Initial bombing was intense and was followed by the attack of the assailants. The breakthrough was simple because the Italians were arranged on three defensive lines, where in the first one the bulk of the troops were piled up, while the other two were poorly defended.

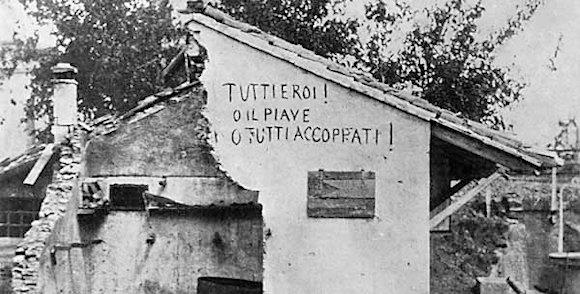

Two days later, Cadorna ordered to retreat beyond the Piave, to save the salvable. Not all of them obeyed orders: the 4th Army, under the command of General Mario Nicolis of Robilant, who defended the sector of the Dolomites, refused to fall over the Piave line, and resisted for a week to the enemy waves, without yielding ground. This attempt to resist cost thousands of lives to the Italian Army that could be spared, since the II and the III Army had to cover the retreat of the IV °, slowing down their retreats and therefore giving the Austrians the opportunity to attack and inflict further losses to the Royal Army. The November 3 forces of the Central Empires were able to reach deep into the Italian territory. Their advance, however, blocked the November 12 on the banks of the Piave, where the Italians had reorganized their forces and were entrenched.

Two days later, Cadorna ordered to retreat beyond the Piave, to save the salvable. Not all of them obeyed orders: the 4th Army, under the command of General Mario Nicolis of Robilant, who defended the sector of the Dolomites, refused to fall over the Piave line, and resisted for a week to the enemy waves, without yielding ground. This attempt to resist cost thousands of lives to the Italian Army that could be spared, since the II and the III Army had to cover the retreat of the IV °, slowing down their retreats and therefore giving the Austrians the opportunity to attack and inflict further losses to the Royal Army. The November 3 forces of the Central Empires were able to reach deep into the Italian territory. Their advance, however, blocked the November 12 on the banks of the Piave, where the Italians had reorganized their forces and were entrenched.

Caporetto became over the years the icon of defeat, the defeat of the defeats, precisely because despite the reduced losses of the Italian military, the refugees were millions and the lost territory was at least 200 km.

The precision with which Cadorna had foreseen the battle, however, suggests a very precise attempt to fall back over the Piave to attest to a new defensive line. He wrote during the half of the 1916 to Prime Minister Salandra: "It is not to be excluded that the necessity of withdrawal from the Isonzo imposes itself [...] on events unfavorable to us, unexpectedly pressing [...]. In such a situation, delaying the withdrawal could overwhelm the army in an irreparable reverse ".

This reveals that the intention to decrease the front line was already present in Cadorna's strategies. The pressing political situation in Russia, which was heating up every day, made even more necessary a new defensive strategy that could block the new Austrian offensives also supported by the departments coming from the East.

If we also look at the Italian losses, we can see that they are on the 10.000 dead, a number quite low compared to the previous battles that had bloodied the Alpine front. However, Caporetto was partially a tactical victory: the refugees, as mentioned earlier, were thousands, if not millions; numerous Italians were taken prisoner by the Austrians; the Austrians advanced very deep into the Italian territory.

The failure of part of the retreat must be attributed, before Cadorna, to Robilant's fanaticism, to Badoglio's tactical inability (which left his side unearthed to the Austrians) and to the inadequacy of other subordinate commanders who allowed Austro-Hungarian forces to to inflict further unavoidable losses on the Royal Army. But this does not preclude that, with the absence of the Battle of Caporetto and the entrenchment on the Piave, Italy would never have won the Great War. In fact, the battle of the Solstice was won thanks to the new attestation of the Italian Army and the shortening of the front, which allowed to reject the Austrian offensive.

Under the command of General Armando Diaz, substitute of Cadorna, the Royal Army attacked the Austrian positions in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, winning the war and leading to the collapse of the ancient Habsburg Empire. The worst defeat imaginable created the basis of triumph.

(photo: web)