The 1961 will be remembered as one of the worst years in South Tyrol's history: in June, in fact, one of the most beautiful regions of Italy leapt into the news for a series of unprecedented terrorist attacks. Every day, as darkness fell, the valleys were shaken by terrible explosions that threw the entire population into a panic. The targets of the bomber were the railway lines, the electric light poles and various infrastructures, symbols of the Italian State. In the province of Bolzano alone, 19 electricity pylons were destroyed, 37 altogether in the whole region: it was a blow that caused the blackout in almost the whole territory. The first to be alerted were the carabinieri: jeeps and trucks came out of the barracks with sirens unfurled, but now there were no more terrorists.

The authors of the bomb attacks belonged to the BAS Befreiungsausschuss Südtirol o Committee for the Liberation of Tyrol: trained persons, capable of shooting with rifles and among them even some veterans of the SS police regiment Bolzano. The independentist instances of the BAS were shared by a minority of the South Tyrolean population who were ill-disposed to the idea of living subject to Italian law; among them many were inspired by the exploits of Andreas Hofer, protagonist, in the nineteenth century, of a struggle without quarter against the French invaders of Napoleon. Until then, the attitude of the Italian government had been quite tolerant, perhaps in the hope of curbing the South Tyrolean ambitions through diplomacy and a series of appropriate concessions.

In the region, in addition to the aforementioned carabinieri, they supervised the police, the finance guard and numerous mountain troops of the 4 ° corps set up precisely in that sector: a force numerically sufficient, but inadequate for a type of counter-terrorism action.

What happened on the night of 11 June 1961 - later renamed "the night of the fires" - was the beginning of an escalation of violence that led to a sudden worsening of relations between Italians and the German minority. In Bolzano the tension was palpable, while in the valleys - a frequent destination for many tourists - the hotels began to empty out causing serious economic repercussions.

After a few years of investigation and investigation, the terrorists were finally brought to justice and for them, in 1963, the doors of the Milan court were opened: after a long and difficult process, the sentence disappointed public expectations, because the penalties imposed were considered too bland. The Fanfani government - with Mario Scelba at the Interiors - put pressure on the judges not to use the heavy hand, hoping to get a fair amount of negotiation with the rebels. The terrorists, deaf to any mediation message, undertook a new and more violent campaign against the representatives of the State. In the 1964, the assassination of the carabiniere Vittorio Trialongo reopened - even more dramatically - the BAS offensive, but this time the government reacted with force and determination.

The Police Forces, in coordination with the army, adopted stricter security measures with arrests and interrogations on the verge of legality: it was necessary to defeat the terrorists undermining the social context in which they lived. The legal squeeze imposed by Rome further heated the spirit of the separatists who inaugurated a new two-year period of terror: between the 1965 and the 1966 trains, barracks and communication routes were targeted. If the situation in the city seemed under control, in the mountainous areas the terrorists were always one step ahead of the Italian military.

The Police Forces, in coordination with the army, adopted stricter security measures with arrests and interrogations on the verge of legality: it was necessary to defeat the terrorists undermining the social context in which they lived. The legal squeeze imposed by Rome further heated the spirit of the separatists who inaugurated a new two-year period of terror: between the 1965 and the 1966 trains, barracks and communication routes were targeted. If the situation in the city seemed under control, in the mountainous areas the terrorists were always one step ahead of the Italian military.

The guerrillas and saboteurs

The modus operandi of the BAS followed the dictates of the clandestine struggle: the terrorists were hiding in a territory that was favorable to them, coming out of the open only to strike or to get supplies. Paths, mountain huts or alpine shelters became shelters for the attackers who, if cornered, knew safe escape routes to cross the border and find protection in Austria.

Alpini, policemen, carabinieri and financiers did not have the necessary experience for this type of confrontation: agile fighters were needed to find the criminals, ready to enter the narrow and steep alpine mule tracks and face a dirty war, made up of ambushes, traps and long stalking .

In September of the 1966, the then undersecretary of defense Francesco Cossiga, had the idea of forming a Special Department in which to gather the police and the army; besides the Alpine troops - already on the spot - the parachutist saboteurs of the commander Antonio Vietri were mobilized. In the sixties, the saboteurs - stationed in Livorno - were still a small unit, unknown to most, whose operational specifications went beyond the training practice of the Thunderbolt. The training process of a saboteur was in fact one of the most complete of the army and besides being able to fight in any geographical environment, he had a wide knowledge of guerrilla and anti-sabotage techniques.

Among the men in the department was Lieutenant Sabotor Aldimiro Cardillo, one of the first summoned by Commander Vietri. "None of us knew what the destination of the new mission was"- recalls Cardillo -"Once at the airport I approached the pilot of the plane to see if he knew anything more than me; He then pointed to a sealed envelope explaining that he had orders to open it only once in flight. All of us had prepared the mountain gear, but no weapons had been delivered to us. Once we arrived at our destination we knew we were in Trentino (at Laives)". As soon as they arrived in the barracks, the "Amaranth Basques" were greeted by a carabinieri officer who, unaware of who his interlocutors were, urged them to prepare for a helicopter training session. At that point, Lieutenant Cardillo started and sternly reminded the carabiniere that they were "saboteurs, they didn't need to be trained and if anything they would be the ones to prepare the others". And indeed so it was: the entrance of the saboteurs into the mixed patrols with the police forces gave a positive turn to the fight against the BAS.

The army's special forces followed long periods of preparation in a mountain environment and most of the children of Livorno had at least one ascent on Mont Blanc to his credit. Enrico Persi Paoli, then a young officer, remembers the type of work to which his comrades were called: it was long patrols and stalking in the high mountains, almost always in prohibitive weather conditions. The danger grew exponentially near the borders or in high-altitude shelters where terrorists hid weapons and supplies. In some huts the rebels of the BAS disguised improvised explosive devices: if a patrol tried to enter without the necessary precautions it would certainly have found death. The saboteurs, the first of the class in matters of explosives thanks to the 80 / B course, escaped several times to these traps, nevertheless the conformation of the land made it difficult to uniformly reclaim all the areas.

Cima Vallona

Cima Vallona

From the hierarchical point of view the men of the commander Vietri formally depended on the police, however, on the field, it was they who led the game. For the battalion - as Simone Baschiera remembers - the experience in Alto Adige was an important occasion in order to put into practice the lessons learned from the Green Berets. In a context unlike Vietnam, the Italian special forces were able to perfectly interpret what was prescribed by the American manuals, adapting each situation to reality: this continuous updating process, acquired directly in the field, made saboteurs an extraordinary weapon.

What happened in June of the 1967 was a consequence of the zeal shown by the Special Department in fulfilling their duties. During a patrol of routine in the area of Comelico Superiore, in Cima Vallona, some Alpine soldiers from the battalion Val Cismon, accompanied by 13 financiers ran into an explosive device hidden near a high voltage pylon. Unfortunately there was a victim, the Alpine Armando Piva, overwhelmed by the explosion. Although the sector did not fall within the competence of the Special Department, the command sent on the spot a detachment led by the captain of the carabinieri paratroopers Francesco Gentile, escorted by saboteurs Lieutenant Mario Di Lecce, sergeant major Marcello Fagnani and sergeant Olivo Dordi. The small group moved towards the accident site with appropriate precautions, but suddenly a new violent roar ripped through the silence of the valley. In a few moments the bodies of Gentile, Dordi and Di Lecce were thrown into the air, while Marcello Fagnani was hit by the shock wave and seriously injured by rock splinters and other material. Everything had happened in an instant: Sergeant Fagnani, in grave danger of life, was transported urgently to the hospital of San Candido where the doctors managed to save his life. His colleagues and friends did not have the same fate, falling victim to the barbarism of the BAS. For the saboteurs battalion it was an unbridgeable loss that deeply hurt the soul of the whole department, despite the fact that in the spirit of a saboteur death was a fact to live with every day. The only contemplated reaction was to continue doing one's duty, trying to protect oneself and the population from further accidents. The captain of the carabinieri of Tuscania it was decorated with the gold medal for military valor, the silver one was awarded to the three saboteurs. Marcello Fagnani, the only survivor, then continued his career in the With Moschin becoming a symbol of heroism and sacrifice for all the children of Nono.

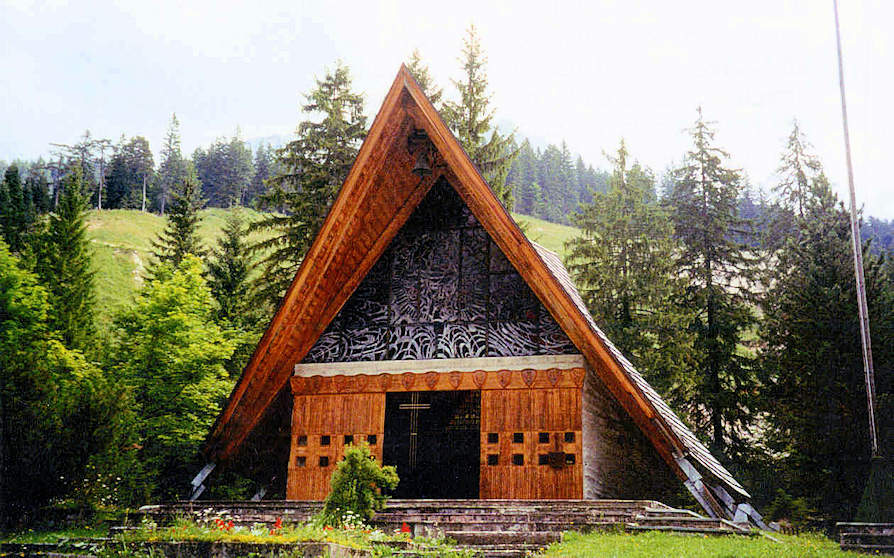

Every year, at the end of June, the ANIE (National Army Raiders Association) together with the 9 ° regiment goes on pilgrimage to the place of the vile attack, celebrating a mass in memory of its fallen at the Tamai Chapel. On that occasion, the highly decorated labaro of the raiders is proudly supported by the bishop, accompanied by the president and Marcello Fagnani, whose face still shows the pain of the loss of company and the injuries suffered, but at the same time a sense of pride and typical pride of those who have done their duty without sparing themselves.

(photo: web)