The Einsatzgruppen, were operating units, special departments, composed of men of the SS and the police, who operated during the Second World War. The main task of the Einsatzgruppen, which operated mainly in the Soviet Union and Poland, was, in the testimony given during the Nuremberg trial by Erich von Dem Bach-Zelewski (1899-1972) (sentenced to life imprisonment he died in the prison hospital of Munich) the annihilation of Jews, Gypsies and political commissioners, obtained through mass shootings and the use of trucks converted into gas chambers.

The origins of the Einsatzgruppen can be traced back to the creation of a special Einsatzkommando wanted by Reinhard Heydrich (1904-1942) to safeguard the government buildings and documents contained therein, during the annexation of Austria by Germany in March 1938. In the same year, during the preparations for the invasion of Czechoslovakia scheduled for the first of October, a department was again activated with similar tasks but that changed its name to Einsatzgruppen. The German plans for the unit to closely follow the advance of the German army, safeguarding public buildings and documents, and interrogating civilian personnel employed by the Czechoslovakian public administration. Unlike the original Einsatzkommando the new department was armed and authorized to kill to carry out its mission. The 1938 Munich agreement prevented the war for which the Einsatzgruppen were originally conceived, but when the German forces in the autumn of the same year occupied the Sudeten, a strong German majority Czechoslovakian region, the department was employed to occupy and check the public offices located in the region. After the full occupation of Czechoslovakia, 15 March 1939 took place, the Einsatzgruppen were re-activated to carry out the occupation and control tasks they were in charge of.

In May 1939 Adolf Hitler decided to invade Poland, initially planned for the 25 August, but then moved to the first of September. For the planned campaign Heydrich again formed the Einsatzgruppen to follow the advance of the German armies but, unlike previous operations, gave the commanders of these units carte blanche to kill those belonging to those groups that the Germans considered hostile. After the invasion of Poland the Einsatzgruppen began that career of death squads, which made them sadly famous. The Polish intelligentsia beheaded, and they killed politicians, scholars, teachers and members of the clergy. This carefully planned operation was part of the scheme of the National Socialist program aimed at transforming the Slavic populations considered "untermenschen-subhuman" into a labor reserve, to be used for the needs of the German Reich. As a result, the Einsatzgruppen's mission was the forced depoliticization of the Polish people and the elimination of the groups that most clearly represented their national identity. In May 1940, during the invasion of Holland, Belgium and France, the Einsatzgruppen were activated once again to follow the advance of the Wehrmact, but, unlike what happened in Poland, in this case they limited themselves to the task original defense of public buildings and documents. In view of the planned invasion of England known as the "Seelöwe" code of operation, plans were made for the creation and use of six Einsatzgruppen who would have had to make numerous arrests as soon as they landed on the island.

In May 1939 Adolf Hitler decided to invade Poland, initially planned for the 25 August, but then moved to the first of September. For the planned campaign Heydrich again formed the Einsatzgruppen to follow the advance of the German armies but, unlike previous operations, gave the commanders of these units carte blanche to kill those belonging to those groups that the Germans considered hostile. After the invasion of Poland the Einsatzgruppen began that career of death squads, which made them sadly famous. The Polish intelligentsia beheaded, and they killed politicians, scholars, teachers and members of the clergy. This carefully planned operation was part of the scheme of the National Socialist program aimed at transforming the Slavic populations considered "untermenschen-subhuman" into a labor reserve, to be used for the needs of the German Reich. As a result, the Einsatzgruppen's mission was the forced depoliticization of the Polish people and the elimination of the groups that most clearly represented their national identity. In May 1940, during the invasion of Holland, Belgium and France, the Einsatzgruppen were activated once again to follow the advance of the Wehrmact, but, unlike what happened in Poland, in this case they limited themselves to the task original defense of public buildings and documents. In view of the planned invasion of England known as the "Seelöwe" code of operation, plans were made for the creation and use of six Einsatzgruppen who would have had to make numerous arrests as soon as they landed on the island.

During the invasion of the Soviet Union carried out by Germany in June 1941, the Einsatzgruppen were guilty of atrocious crimes (in the image on the left a teenager near the bodies of family members shortly before being murdered) for which they are still sadly remember, killing Jews, partisans and members of the Communist Party on a much larger scale than in Poland. Four fully motorized Einsatzgruppen were used for operation "Barbarossa" and therefore able to quickly reach every area of the extended eastern front operating in the newly liberated areas of the army's fighting units. The areas of expertise were:

During the invasion of the Soviet Union carried out by Germany in June 1941, the Einsatzgruppen were guilty of atrocious crimes (in the image on the left a teenager near the bodies of family members shortly before being murdered) for which they are still sadly remember, killing Jews, partisans and members of the Communist Party on a much larger scale than in Poland. Four fully motorized Einsatzgruppen were used for operation "Barbarossa" and therefore able to quickly reach every area of the extended eastern front operating in the newly liberated areas of the army's fighting units. The areas of expertise were:

Einsatzgruppe A, used in the Baltic republics;

Einsatzgruppe B, employed in Belarus and in the direction of Moscow;

Einsatzgruppe C, used for the north and the central part of Ukraine;

Einsatzgruppe D, used in southern Ukraine, Crimea and Caucasus.

Each Einsatzgruppe was divided into operating units called "Einsatzkommandos and Sonderkommandos", logistically dependent on the army groups of the German army, but totally disengaged for the special tasks entrusted to it. Having to refer exclusively to the SS-und Polizeiführer (commander of the SS and the police) of the employment area. The SS-und Polizeiführer, the supreme operational authority in the field, responded directly to the Reichssicherheitshauptamt RSHA (central security office of the Reich), the SS, and its commander Himmler, who directly informed the Führer. Heydrich's directives set a precise course of action:

1) The elimination of the cadres of the Communist Party, of the political commissioners and of those who opposed German liberation.

2) The instigation of pogroms against the local population of Jewish origin.

Within a short time the Einsatzgruppen were increasingly involved in mass murder. The most lethal of the Einsatzgruppen engaged in the Soviet Union was the Einsatzgruppe A which operated in the Baltic states (Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia). It was the first of these units, which accomplished the intended task, the elimination of all the Jews in its area of competence, making it "judenfrei" (free from Jews). After December 1941 the other three Einsatzgruppen began what the historian Raul Hilberg called the second sweep, ended in the summer 1942, trying to achieve the results obtained by Einsatzgruppe A. It is estimated that the Einsatzgruppen killed in the Soviet Union about 1.500.000 of people: Jews, communists, prisoners of war and Gypsies. In addition to the extermination tasks the Einsatzgruppen were also widely used in the anti-partisan war.

Within a short time the Einsatzgruppen were increasingly involved in mass murder. The most lethal of the Einsatzgruppen engaged in the Soviet Union was the Einsatzgruppe A which operated in the Baltic states (Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia). It was the first of these units, which accomplished the intended task, the elimination of all the Jews in its area of competence, making it "judenfrei" (free from Jews). After December 1941 the other three Einsatzgruppen began what the historian Raul Hilberg called the second sweep, ended in the summer 1942, trying to achieve the results obtained by Einsatzgruppe A. It is estimated that the Einsatzgruppen killed in the Soviet Union about 1.500.000 of people: Jews, communists, prisoners of war and Gypsies. In addition to the extermination tasks the Einsatzgruppen were also widely used in the anti-partisan war.

The operations of the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union represent the earliest stages of what the National Socialist authorities defined as the final solution to the Jewish question, the extermination of the Jewish people. Until then Hitler and the leaders of the Nazi state had elaborated numerous plans to make Germany and the areas subjected to it "judenfrei", which did not necessarily provide for physical extermination. Some solutions were under study: the voluntary emigration of the Jews, the transfer to Madagascar, the creation of a Jewish reserve in Poland, or in the Soviet Union. Starting from July 1941, the situation changed and the systematic massacres of the Einsatzgruppen demonstrate that a radical and definitive decision had been taken, albeit initially limited to the Soviet Jews only. The subsequent creation of the extermination camps was only a technical improvement to alleviate the task of the Einsatzgruppen, making the impersonal killing method less burdensome for those engaged in it. The formalization of the directives for the final solution, arrived in January 1942, during the Wannsee conference, but there is clear evidence that Hitler had already previously decided the fate of the Jewish people.

The Einsatzgruppen closely followed the advance of the German armed forces and preferred their operations in towns and villages, where substantial Jewish communities lived. As soon as they arrived in the city, they issued decrees that ordered all Jewish citizens to present themselves at a meeting point, from which they would be resettled to other places to perform a mandatory work service. The orders posted on the streets unequivocally clarified that those who did not show up would be killed. It should be noted that, at least in the first period, Soviet Jews were unaware of the terrible conditions of their Polish coreligionists, locked up in ghettos because until the outbreak of the conflict the Soviet Union, benevolently neutral with Germany after the signing of the Molotov- Ribbentrop had carefully filtered and hidden the news about the Nazi excesses in Poland.

For this reason the Jews were easily deceived by the lie of resettlement, especially given the fatal consequences that would have caused the non-execute order of the occupation authorities. The people gathered by deception were transferred near the city, in secluded areas previously selected by the men of the Einsatzgruppen. The unfortunates were led to large ditches already excavated, old disused shipyards, or deep ravines (eg Babi Yar, where the massacre of the Jewish population of Kiev took place) and completely stripped, the clothes were then sent to the German welfare agencies. Naked, they had to approach the edge of the graves where the often drunken executioners killed them with machine-gun or pistol shots. In many cases the victims were forced to lie down on the layer of corpses of those who had already been killed before being hit by a barrage of machine gun, or by a bullet in the back of the head. Newborns were often thrown into the air and used as a target for the executioners' shots. Once the Aktion ended, a term used to indicate the massacres, the pits to prevent the development of epidemics, were sprinkled with lime and covered with earth to erase the traces of the crimes committed. Given the excitement of the operations it was not unusual for some victims not to be killed, but only wounded and then buried alive when the pit was covered. There are some testimonies of survivors who managed to save themselves, coming out of the pits at night. In the following years, when the certainty in the German victory was now compromised, an exhumation operation was launched by the SS, to definitively eliminate the evidence of crimes by cremating corpses in large fires. The operation, supervised by Paul Blobel, former commander of an Einsatzkommando, took the code name of "Sonderaktion 1005", and saw the employment of numerous teams composed of Jewish prisoners, who were themselves eliminated, after having carried out the work for the purpose of preserve the secret. The massacres carried out by shooting, immediately showed two negative elements:

For this reason the Jews were easily deceived by the lie of resettlement, especially given the fatal consequences that would have caused the non-execute order of the occupation authorities. The people gathered by deception were transferred near the city, in secluded areas previously selected by the men of the Einsatzgruppen. The unfortunates were led to large ditches already excavated, old disused shipyards, or deep ravines (eg Babi Yar, where the massacre of the Jewish population of Kiev took place) and completely stripped, the clothes were then sent to the German welfare agencies. Naked, they had to approach the edge of the graves where the often drunken executioners killed them with machine-gun or pistol shots. In many cases the victims were forced to lie down on the layer of corpses of those who had already been killed before being hit by a barrage of machine gun, or by a bullet in the back of the head. Newborns were often thrown into the air and used as a target for the executioners' shots. Once the Aktion ended, a term used to indicate the massacres, the pits to prevent the development of epidemics, were sprinkled with lime and covered with earth to erase the traces of the crimes committed. Given the excitement of the operations it was not unusual for some victims not to be killed, but only wounded and then buried alive when the pit was covered. There are some testimonies of survivors who managed to save themselves, coming out of the pits at night. In the following years, when the certainty in the German victory was now compromised, an exhumation operation was launched by the SS, to definitively eliminate the evidence of crimes by cremating corpses in large fires. The operation, supervised by Paul Blobel, former commander of an Einsatzkommando, took the code name of "Sonderaktion 1005", and saw the employment of numerous teams composed of Jewish prisoners, who were themselves eliminated, after having carried out the work for the purpose of preserve the secret. The massacres carried out by shooting, immediately showed two negative elements:

1) The psychological collapses that involved the staff: to try to mitigate the horror of the task that they were called to play, considered necessary and right by the Nazis. The executioners received additional rations of alcohol, often working completely drunk. Despite this, there were numerous cases of internment in psychiatric nursing homes and several suicides among the ranks of the Einsatzgruppen.

1) The psychological collapses that involved the staff: to try to mitigate the horror of the task that they were called to play, considered necessary and right by the Nazis. The executioners received additional rations of alcohol, often working completely drunk. Despite this, there were numerous cases of internment in psychiatric nursing homes and several suicides among the ranks of the Einsatzgruppen.

2) Himmler's fear that the men of the SS, considered an elite that should have embody all the superior characteristics proper to the Aryan race, could be contaminated by the brutality of the work they were obliged to perform. The same Himmler, who famously abhorred the sight of the blood, assisted in July of the 1941 to an Aktion of the Einsatzgruppen remaining deeply shaken. For this reason Himmler, worried about the health and the moral integrity of his men, ordered to find new methods, less bloody, to complete the task assigned to the SS entrusting the task to Arthur Nebe, commander of Einsatzgruppe B. Arthur Nebe had previously been head of the Kripo (German criminal police), and had been involved in the program of elimination of the disabled called "Aktion T4", suspended at the end of August 1941, due to vehement protests of the German population , during which the use of gas chambers functioning with pure carbon monoxide had been experimented. This method had given excellent results, making the killing more impersonal, who opened the tap of the cylinders where the gas was contained had no contact with the victims while waiting in the sealed gas chamber.

In September 1941, Nebe requested a chemistry expert in Berlin who could technically help him find a solution to the problem. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Albert Widmann of the Institute of Criminal Technology arrived in Minsk, the seat of Nebe's command. Nebe and Widmann initially studied a method of killing with explosives by enclosing 25 psychiatric patients in two bunkers and blowing them up. The experiment proved to be disastrous and the explosion killed only part of the patients. At this point, Widmann and Nebe, mindful of the experience of the "T4" program, thought to use gas chambers operating on carbon monoxide and, a few days after the failed experiment with explosives, they carried out a test near Mogilev. The experiment was performed on about thirty patients in an asylum, locked inside a sealed hospital lane, inside which two pipes connected to the exhaust gases of a motor vehicle entered. After an initial problem related to the low power of the vehicle used, all the patients died within a few minutes, intoxicated by the carbon monoxide produced by the exhaust gases. The success of the experiment showed that this was the way to go, even if there were some technical problems to solve. The Einsatzgruppen were mobile units operating on a very large front and it would not have been efficient to link their operations to fixed installations such as the gas chambers of the Aktion T4. The idea of using exhaust gas was instead a winner, because the production of pure carbon monoxide, previously used, was very expensive and the German chemical industry was able to produce only limited quantities. This is why Nebe, in collaboration with Dr. Hess, Widmann's superior, studied a truck-based solution with a sealed loading floor connected to the exhaust fumes produced by the engine via a piping system. In this way, it would create real mobile gas chambers, called "Gaswagen", totally self-sufficient also for the supply of gas. Having obtained Heydrich's approval, the idea was perfected by Walter Rauff, head of the technical department of the RSHA, who designed trucks disguised as ambulances, of two different sizes and which could contain 140 or 90 victims simultaneously.

The trucks of death, began to be used by the Einsatzgruppen for extermination operations, between the end of November and the beginning of December 1941, but never completely replaced the old method based on shooting. The truck workers loaded the victims, transporting their sad cargo to the place identified for burial. Death occurred after 15-30 minutes, and any survivors were killed with a blow to the back of the head. By the middle of the 1942, 30 converted trucks were produced and delivered to the Einsatzgruppen, produced by the Berlin-based company Gabschat Farengewerke Gmbh. The first extermination camp made 8 December 1941 operational in Chełmno, used three mobile gas chambers before the method was further perfected for the new fields of the "Reinhard" operation, which used instead fixed gas chambers. The use of exhaust gases was not however abandoned and, in the following years, only Auschwitz and Majdanek differentiated themselves using the Zyklon B gas as a toxic agent.

The trucks of death, began to be used by the Einsatzgruppen for extermination operations, between the end of November and the beginning of December 1941, but never completely replaced the old method based on shooting. The truck workers loaded the victims, transporting their sad cargo to the place identified for burial. Death occurred after 15-30 minutes, and any survivors were killed with a blow to the back of the head. By the middle of the 1942, 30 converted trucks were produced and delivered to the Einsatzgruppen, produced by the Berlin-based company Gabschat Farengewerke Gmbh. The first extermination camp made 8 December 1941 operational in Chełmno, used three mobile gas chambers before the method was further perfected for the new fields of the "Reinhard" operation, which used instead fixed gas chambers. The use of exhaust gases was not however abandoned and, in the following years, only Auschwitz and Majdanek differentiated themselves using the Zyklon B gas as a toxic agent.

The "Einsatzgruppen" were never permanent units but rather departments created using personnel from the ranks of the SS, the SD and the various departments of the German police "Ordnungspolizei", "Gendarmeria", "Kripo" and "Gestapo". The departments counted from the 600 to the 1000 men, received before being employed, a training of a duration varying from a few weeks to a few months. Once the operations were complete, the "Einsatzgruppen" were dissolved, although generally the same staff, already expert, was recalled, in case there was the need to reform them for new jobs. The "Einsatzgruppen" were assisted in their duties by other Axis forces, by Wehrmacht soldiers and the Waffen SS, or by German police battalions. During the massacres in the Soviet Union, the "Einsatzgruppen" recruited local anti-Semites, particularly in Lithuania and Ukraine, which were distinguished by their brutality. Einsatzgruppe A engaged in the Baltic republics, subdivided into "Sonderkommandos 1 / a and 1 / b", and "Einsatzkommandos 2 and 3". In October of the 1941, Einsatzgruppe A had the following personnel:

18 Administration

87 auxiliary police

13 Women's Department

89 Gestapo

51 interpreters

Criminal Police (Kri.Po.) 41

172 motorcyclists

Police Order (Or.Po.) 133

Radio operators 8

Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst) 35

Operators at 3 teletypes

Waffen-SS 340

"Einsatzgruppe B" engaged in Belarus, divided into "Sonderkommandos 7 / a and 7 / b", and "Einsatzkommandos 8 and 9", a special unit in case Moscow had been conquered.

"Einsatzgruppe C" for the north and the central part of Ukraine, divided into "Sonderkommandos 4 / a and 4 / b" "Einsatzkommandos 5 and 6".

"Einsatzgruppe D" for the south of Ukraine, Crimea and the Caucasus, divided into "Sonderkommandos 10 / a and 10 / b", and "Einsatzkommandos 11 / a, 11 / be 12".

Commanders

Einsatzgruppe A: SS-Brigadeführer Dr.Franz Walter Stahlecker (until 23 March 1942)

Einsatzgruppe B: SS-Brigadeführer Arthur Nebe (until October 1941)

Einsatzgruppe C: SS-Gruppenführer Dr. Otto Rasch (until October 1941) SS-Gruppenführer Erich Naumann (1941-1943)

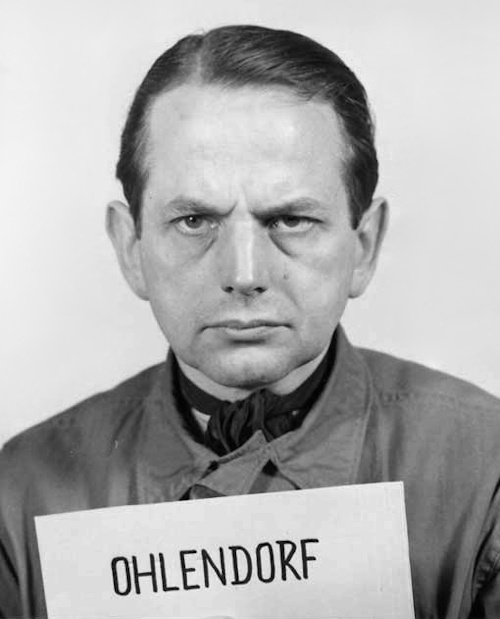

Einsatzgruppe D: SS-Gruppenführer Prof. Otto Ohlendorf (until June 1942)

The process at the Einsatzgruppen

The trial at the Einsatzgruppen, officially "The United States of America Vs. Otto Ohlendorf "was the ninth of the twelve war crimes trials held by the US authorities in Nuremberg. The twelve trials were celebrated exclusively by US military courts and not before the International Military Tribunal (IMT), which had promoted the main Nuremberg trial, against the leadership of National Socialist Germany. The twelve US trials are collectively known as secondary processes in Nuremberg, more properly, "Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals (NMT)". The accused 24s were all officers of the Einsatzgruppen heavily involved in the massacre operations.

The court ruled: "In this case the defendants are not simply accused of planning or directing massive killings through command channels. It has been demonstrated in great detail that these men took an active role in the field by supervising, controlling, directing and actively taking part in the bloody massacre.". The judges of this case, belonging to the II-A military court, were: Michael A. Musmanno, president of Pennsylvania, John J. Speight of Alabama, and Richard D. Dixon of North Carolina. The head of the indictment was Telford Taylor and the prosecutor Benjamin B. Ferencz. The charge was initially filed on 3 July and modified on 29 July 1947, to include the accused Steimle, Braune, Hänsch, Strauch, Klingelhöfer and von Radetzky. The process took place between the 29 September 1947, and the 10 April 1948.

The court ruled: "In this case the defendants are not simply accused of planning or directing massive killings through command channels. It has been demonstrated in great detail that these men took an active role in the field by supervising, controlling, directing and actively taking part in the bloody massacre.". The judges of this case, belonging to the II-A military court, were: Michael A. Musmanno, president of Pennsylvania, John J. Speight of Alabama, and Richard D. Dixon of North Carolina. The head of the indictment was Telford Taylor and the prosecutor Benjamin B. Ferencz. The charge was initially filed on 3 July and modified on 29 July 1947, to include the accused Steimle, Braune, Hänsch, Strauch, Klingelhöfer and von Radetzky. The process took place between the 29 September 1947, and the 10 April 1948.

The accusations were:

1) Crimes against humanity, through persecution on political, racial and religious grounds, murder, extermination, detention and other inhuman acts committed against civilians, including German and other nationals, as part of a systematic genocide project.

2) War crimes for the same reasons; mistreatment of prisoners of war and the civilian population of the occupied territories and unbridled destruction and unjustified devastation, military necessities in violation of international conventions, art.43 and 46 of the Hague Conventions of the 1907 and the prisoners of war of the Convention of Geneva of the 1929.

3) Membership of criminal organizations, the SS, the SD and the Gestapo, from which many of the members of the Einsatzgruppen came, had been declared criminal organizations during the previous Nuremberg trial. All the accused were accused of all the charges and all declared themselves "not guilty". The court found them guilty of all charges except Rühl and Graf, found guilty only of the third charge.

The defendants

Of the 14 death sentences, four were executed; the others were commuted to captivity in the 1951 amnesty. In the 1958 all inmates were released.

Otto Ohlendorf

SS-Gruppenführer; member of the SD; commander of the Einsatzgruppe D- death by hanging the 7 June 1951.

Heinz Jost-

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the SD; commander of Einsatzgruppe A- Ergastolo, under penalty of commuted to 10 years in prison.

Erich Naumann

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the SD; commander of Einsatzgruppe B - death by hanging, 7 June 1951.

Otto Rasch

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the SD and the Gestapo; commander of the Einsatzgruppe C- Dismissed from the trial the 5 February 1948, due to health conditions.

Franz Six

SS-Brigadeführer; member of the SD; commander of the Vorkommando Moscow Einsatzgruppe B- 20 years in prison, under penalty of commuted to 15 years.

Paul Blobel

SS-Standartenführer; member of the SD; commander of the Sonderkommando 4a Einsatzgruppe C- death by hanging the 7 Jun 1951.

Walter Blume

SS Standartenführer; member of the SD and the Gestapo; commander of the Sonderkommando 7a Einsatzgruppe B - death by hanging, sentence commuted to 25 years in prison.

Martin Sandberger

SS Standartenführer; member of the SD; commander of the Sonderkommando 1a Einsatzgruppe A - death by hanging, sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

Willy Seibert

SS Standartenführer; member of the SD; Deputy Head of the Einsatzgruppe D-death by hanging, punishment commuted to 15 years in prison.

Eugen Steimle

SS Standartenführer; member of the SD; commander of the Sonderkommando 7 ° - Einsatzgruppe B, and of the Sonderkommando 4a Einsatzgruppe C - death by hanging, penalty commuted to 20 years in prison.

Ernst Biberstein

SS Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD; commander of the Einsatzkommando 6 -Einsatzgruppe C- death by hanging, sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

Werner Braune

SS Obersturmbannführer, member of the SD and Gestapo; commander of the Sonderkommando 11b-Einsatzgruppe D- death by hanging executed the 7 June, 1951.

Walter Hänsch

SS Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD; commander of the Sonderkommando 4b Einsatzgruppe C- death by hanging, penalty commuted to 15 years.

Gustav Nosske

SS Obersturmbannführer; member of the Gestapo; commander of the Einsatzkommando12-Einsatzgruppe D life imprisonment, commuted to 10 years in prison.

Adolf Ott

SS Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD; commander of the Sonderkommando 7b-Einsatzgruppe B - death by hanging, sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

Eduard Strauch

SS Obersturmbannführer; member of the SD; commander of the Einsatzkommando 2-Einsatzgruppe A-death by hanging delivered to the Belgian authorities; he died in the hospital.

Emil Haussmann

SS Sturmbannführer; member of the SD; official of the Einsatzkommando 12-Einsatzgruppe D-suicide after the sentence the 31 July, 1947.

Waldemar Klingelhöfer

SS Sturmbannführer; member of the SD; official of the Sonderkommando 7b Einsatzgruppe B - death by hanging, sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

Lothar Fendler SS Sturmbannführer; member of the SD; Deputy Head of the Sonderkommando 4b -Einsatzgruppe C-10 years, penalty reduced to 8 years.

Waldemar von Radetzky

SS Sturmbannführer; member of the SD; deputy responsible for the Sonderkommando 4a Einsatzgruppe C-20 years released.

Felix Rütl

SS Hauptsturmführer; member of the Gestapo; official Sonderkommando 10b Einsatzgruppe D-10 years; released.

Heinz Schubert

SS Obersturmführer, member of the SD; officer of the Einsatzgruppe D- death by hanging, penalty commuted to 10 years.

Mathias Graf

SS Untersturmführer; member of the SD; official of the Einsatzkommando 6-Einsatzgrupp D, issued for expiry of the indictment terms.

REFERENCES

1) History Controversial of the Second World War - vol. 1-8 De Agostini Geographical Institute, 1977

2) SVEN HASSEL - Assault battalion - Longanesi 1971

3) PAUL CARREL - Russia 1941-1945, Operation Barbarossa, vol I, II - Longanesi, 1967

6) PIETRO CAPORILLI - 7 years of war (photostory of the second world war) vol I, II, III Edizioni Ardita, Rome 1965.

7) MARIO VERONESI - My Russia (diary of a war, thoughts, memories, stories of Russia's 1941-1943 campaign), Italian University Press, 2009

Internet

From the Mazal Library site - Nuremberg trials.

US Holocaust Memorial Museum-Description

www.wikipedia.it http://www.ess.uwe.ac.uk/genocide/cntrl10_trials.htm#Einsatzgruppen

http://www.nizkor.org/hweb/orgs/german/einsatzgruppen/esg/mapkilling.html

(photo: Bundesarchiv / United States Holocaust Memorial Museum / web)