The morning of 28 October 1917 is a prime example of how in the war the fortunes can suddenly turn upside down, in spite of any precaution you may have taken. In the context of the brilliant breakthrough operation in Tolmin and Caporetto, with the Italian troops fleeing and the rapidly advancing German-Austrian forces, General Albert von Berrer was killed during an innocuous transfer operation for the unexpected meeting with an Italian patrol .

In the dramatic days of retreat to the Tagliamento, the event aroused not a little enthusiasm, but the circumstances in which this happened were the subject of numerous misunderstandings. The news was communicated to the public on October 30 by the Stefani agency, the only one to have the exclusivity for the diffusion of the dispatches of the General Staff, and was later taken up by the national and foreign press. Already the November 5 the "The New York Times" titled "German general killed", even if the location was erroneously placed on the eastern front, to be precise Riga. The November 18 instead went out in the Corriere della Sera, to portray the event, a lucky illustrated table by Achille Beltrame, who over the years remained the symbol of that daring stroke of luck. The protagonists are two carabinieri (1) and indeed the paternity of the action represented the first ambiguity formed. The merit, in the chaotic "after Caporetto", was attributed to Carabinieri, Bersaglieri and even bold, the latter involved in the defense of Udine. And although the following day Corriere published an article in which he recognized himself, even with inaccuracies about the course of the action (2), merit to the sergeant Bersagliere Giuseppe Morini, in the collective imagination remained the weapon the undisputed protagonist. This at least until the testimonies of the participants were available. On the first of December, the illustrated Century gave the interview to Morini, at that moment convalescing at the "Fratelli Bandiera" hospital in Milan after being injured in the left arm in the fights between Paludea and Travésio of 3 November. Equally important was the testimony of the arrested Lieutenant von Graevenitz and the sources of German production, including the biography of General von Berrer by Hanns Möller-Witten published in the 1941 and the work of General Krafft von Dellmensingen Der Durchbruch am Isonzo. The considerable attention of the press is well explained by the prevailing defeatism of those days. The death of an enemy general, although militarily not so relevant, represented a panacea for Italian morale. It meant that, despite the defeat, he was still able to grasp some success. For the German troops it was instead one shock ; the general was in fact the object not only of hierarchical respect, but of a real admiration for his human qualities.

Let's see now how the facts took place starting with the German side.

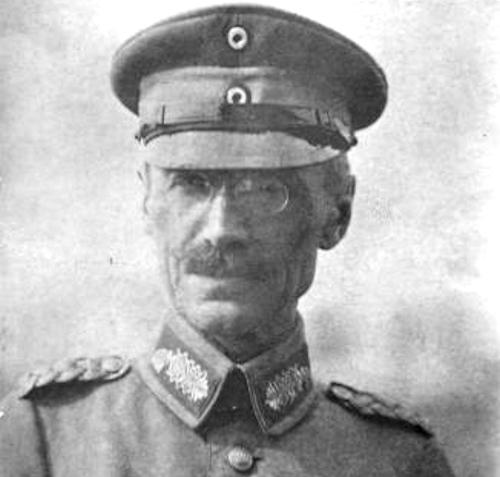

Albert von Berrer, 1857 Class, born in Unterkochen, Württemberg, after the gymnasium in Heilbronn and the high school in Stuttgart, follows in the footsteps of two of his brothers taking up a military career. He volunteered in the regiment grenadiers "Konigin Olga" in Stuttgart from which he will be promoted to second lieutenant in the 1876. At the outbreak of the Great War he was a lieutenant general of the 31a Infantry Division for the Lorraine sector, framed in the 21st Corps of the 6th Army of the Crown Prince Rupprecht. The first clashes, however, will support them on the eastern front, in February of 1915, during the second battle of the Masuri lakes. In the following years we find him always on the eastern front: in the '16 is in command of the XXI Corps in aid to the Austro-Hungarians, committed to countering the offensive Brusilov, while in the summer of' 17 stands out during the offensive Karensky, thus earning the Pour le Mérite, the highest imperial military honor. In October of the same year he was part of the Germanic shipping body sent to support the Austrians on the Italian front. This is the 14th Army of General Otto von Below, consisting of four Army Corps for a total of 6 German divisions and Austro-Hungarian 8 (3 in reserve). Von Berrer is in command of the 1st Army Corps, composed of the 26a Infantry Division of Wurttemberg and the 200a (Prussian) division Jäger. Following the breakthrough of the Isonzo front to Tolmino and Caporetto, it heads towards Udine. The night of the 27 are in San Pietro al Natisone and the following dawn is occupied the village of Azzida. At the 8 in the morning the general in his car takes the road Cividale-Udine. His first helper, Major Vender, the cavalry captain Boeszoermeny and Lieutenant von Graevenitz accompany him. Sergeant Freitag and Corporal Koenemann are at the helm. The objective is to lead the advance on the field, reuniting with elements of the 26th division that, according to the orders given, should already have occupied Udine. Von Berrer disdained the rear and was an advocate of the war of movement in which the German army excelled and in which it could finally return to express itself. The entire campaign was in fact propped up by avant-garde troops who quickly, without worrying about the enemy cornerstones and the side cover, continued to advance, pressing the retreating Italians, preventing their reorganization. In light of this the lack of a stock is perfectly understandable. What the general however ignored was that Udine was still firmly in Italian hands. Where was the 26a division then? Von Dellmensingen, at the general time of the Deutsche Alpenkorps, took part in his work Der Durchbruch am Isonzo. In the nocturnal march to Udine he found himself behind the 26a, which, shortly after Ziracco, diverted from the main road (Cividale Udine) ending up lost in the countryside, south of the Gotthard bridge that he would have to cross instead.

Albert von Berrer, 1857 Class, born in Unterkochen, Württemberg, after the gymnasium in Heilbronn and the high school in Stuttgart, follows in the footsteps of two of his brothers taking up a military career. He volunteered in the regiment grenadiers "Konigin Olga" in Stuttgart from which he will be promoted to second lieutenant in the 1876. At the outbreak of the Great War he was a lieutenant general of the 31a Infantry Division for the Lorraine sector, framed in the 21st Corps of the 6th Army of the Crown Prince Rupprecht. The first clashes, however, will support them on the eastern front, in February of 1915, during the second battle of the Masuri lakes. In the following years we find him always on the eastern front: in the '16 is in command of the XXI Corps in aid to the Austro-Hungarians, committed to countering the offensive Brusilov, while in the summer of' 17 stands out during the offensive Karensky, thus earning the Pour le Mérite, the highest imperial military honor. In October of the same year he was part of the Germanic shipping body sent to support the Austrians on the Italian front. This is the 14th Army of General Otto von Below, consisting of four Army Corps for a total of 6 German divisions and Austro-Hungarian 8 (3 in reserve). Von Berrer is in command of the 1st Army Corps, composed of the 26a Infantry Division of Wurttemberg and the 200a (Prussian) division Jäger. Following the breakthrough of the Isonzo front to Tolmino and Caporetto, it heads towards Udine. The night of the 27 are in San Pietro al Natisone and the following dawn is occupied the village of Azzida. At the 8 in the morning the general in his car takes the road Cividale-Udine. His first helper, Major Vender, the cavalry captain Boeszoermeny and Lieutenant von Graevenitz accompany him. Sergeant Freitag and Corporal Koenemann are at the helm. The objective is to lead the advance on the field, reuniting with elements of the 26th division that, according to the orders given, should already have occupied Udine. Von Berrer disdained the rear and was an advocate of the war of movement in which the German army excelled and in which it could finally return to express itself. The entire campaign was in fact propped up by avant-garde troops who quickly, without worrying about the enemy cornerstones and the side cover, continued to advance, pressing the retreating Italians, preventing their reorganization. In light of this the lack of a stock is perfectly understandable. What the general however ignored was that Udine was still firmly in Italian hands. Where was the 26a division then? Von Dellmensingen, at the general time of the Deutsche Alpenkorps, took part in his work Der Durchbruch am Isonzo. In the nocturnal march to Udine he found himself behind the 26a, which, shortly after Ziracco, diverted from the main road (Cividale Udine) ending up lost in the countryside, south of the Gotthard bridge that he would have to cross instead.

The story is completed by Lieutenant General Eberhard von Hofacker, then in command of the 26a. "... we were cut off from any connection with the rear so that the Italian departments retreating from the Corada were heading south of Cividale and all converged on Udine, cutting the road behind. We therefore had to defend ourselves from all sides as a hedgehog."A bit of clarity is urgent. Because of the darkness the division is lost, ending south of the intended goal. It is located in Selvis, flattened on one side by the river Torre in flood, and on the other by the same Italian troops in retreat on Udine, with which engages in fire fighting. No telephone links are isolated. To complicate the whole, the Alt-Württemberg regiment is attacked by numerous Italian prisoners who, after taking into account the growing difficulties of the Germans, resume their arms. The intervention of the Olga Regiment allows the Germans to re-establish the situation. All of this obviously Von Berrer ignores him.

Let's now return to our unfortunate general. Left Azzida, after Remanzacco meets elements of the 6 ° Battalion Jäger (200a division). Captain Von Blankenburg who commands them informs his superior of the absence, as far as I know, of German troops later. Von Berrer does not trust and continues undaunted, he knows that the 26a is advanced at night and has full confidence in his men, impossible that they are not already in Udine, even with a little 'luck will also surprised Cadorna to pack up (2). His confidence is partly cracked when even Colonel Stümke of the 125 ° infantry regiment, met almost simultaneously, confesses that he does not know where the other departments of 26a have ended. Von Berrer then sends the Major Vender back on foot with the order to bring all the units of the sector together on Udine. Although from Remanzacco to the meeting with Stümke had traveled only two kilometers we can imagine how advancing on foot in the muddy ground seemed ungrateful to the zealous major. In hindsight, he will have thanked his lucky star. Meanwhile, the general continues the march towards the Tower, but finding the bridge blown up by the Italians in retreat. No problem for our intrepid general who manages to wade with the car and then re-enter the main road. We are now at the gates of San Gottardo. The scene of the ford also presents an unexpected witness. This is Lieutenant Frederic Henry, aka Ernest Hemingway who in his A Farewell to Arms give us this description: "When I was there I turned to look. A little further up there was another bridge, and a mud-colored car was driving along it. The shoulders were high and the car disappeared back there but I saw the head of the driver slide over the man next to him and the two of them sitting back. All wore German helmets. Then the car came out of the bridge and disappeared into the trees and abandoned vehicles on the road"The bridge, which in the novel has remained standing as a pretext for a generous invective on the chaos of the retreat, is shortly after crossed by a group of Germans on bicycles. Almost certainly part of the 6 ° Jäger cyclists company met outside Remanzacco by the general.

Let's go back to reality now. We are at the gates of San Gottardo. The epilogue is literally around the corner.

Shortly after entering the town, which apparently seems deserted, the car finds itself blocked by Italian soldiers, who suddenly emerge from the bend in the road. Let us now allow von Graevenitz to intervene who, after his imprisonment, drew up the testimony reported in H. Möller. Italians are half company, about sixty. The shocked drivers stop the vehicle and the Italians open fire. Immediately Von Berrer is hit in the shoulder, but the general does not lose his coolness and shouts “Everyone out! Hand the guns! Shoot! ”The occupants exit and begin to fire back, while the terrified drivers attempt to restart the car to disengage from the fight. But, to quote Sergio Leone: "When a man with a gun meets a man with a gun, the one with the gun is a dead man". In this case we are 3 guns against sixty guns. You definitely learn. In fact, Captain Boeszoermeny, hit, immediately falls into the ditch. The lieutenant tries to shake him but nothing to do; is dead. Meanwhile, the general is also shot to death, but von Graevenitz, so committed to saving his life, cannot give an eyewitness account of this. In the meantime, given the impossibility of maneuvering under the hail of bullets, the drivers abandoned the vehicle. Von Graevenitz, then left alone, throws himself behind the car using it as a cover and then runs towards the houses but, without realizing it, is attacked from behind and immobilized by an Italian soldier. Wounded and prisoner joins the retreating columns. Our drivers, on the other hand, were luckier; although one was wounded they manage to reach Remanzacco where they inform Major Vender of the incident. About an hour and ten minutes after the incident, the Jägers of the 6th occupy the Gotthard, now effectively uninhabited. The show is a machine riddled with seventeen bullet holes and the bodies of the two officers stripped of all possessions, including the badges of the ranks. To complete the tragedy will arrive shortly after the twenty-year-old son of the general, the lieutenant of the dragons Wanhart. The bodies will be transported to Cividale and buried on November 22st. Von Berrer will then be exhumed and on XNUMX December buried at the Pragfriedhof in his Stuttgart with a ceremony with great pomp which was attended by King William II of Württemberg (3).

Shortly after entering the town, which apparently seems deserted, the car finds itself blocked by Italian soldiers, who suddenly emerge from the bend in the road. Let us now allow von Graevenitz to intervene who, after his imprisonment, drew up the testimony reported in H. Möller. Italians are half company, about sixty. The shocked drivers stop the vehicle and the Italians open fire. Immediately Von Berrer is hit in the shoulder, but the general does not lose his coolness and shouts “Everyone out! Hand the guns! Shoot! ”The occupants exit and begin to fire back, while the terrified drivers attempt to restart the car to disengage from the fight. But, to quote Sergio Leone: "When a man with a gun meets a man with a gun, the one with the gun is a dead man". In this case we are 3 guns against sixty guns. You definitely learn. In fact, Captain Boeszoermeny, hit, immediately falls into the ditch. The lieutenant tries to shake him but nothing to do; is dead. Meanwhile, the general is also shot to death, but von Graevenitz, so committed to saving his life, cannot give an eyewitness account of this. In the meantime, given the impossibility of maneuvering under the hail of bullets, the drivers abandoned the vehicle. Von Graevenitz, then left alone, throws himself behind the car using it as a cover and then runs towards the houses but, without realizing it, is attacked from behind and immobilized by an Italian soldier. Wounded and prisoner joins the retreating columns. Our drivers, on the other hand, were luckier; although one was wounded they manage to reach Remanzacco where they inform Major Vender of the incident. About an hour and ten minutes after the incident, the Jägers of the 6th occupy the Gotthard, now effectively uninhabited. The show is a machine riddled with seventeen bullet holes and the bodies of the two officers stripped of all possessions, including the badges of the ranks. To complete the tragedy will arrive shortly after the twenty-year-old son of the general, the lieutenant of the dragons Wanhart. The bodies will be transported to Cividale and buried on November 22st. Von Berrer will then be exhumed and on XNUMX December buried at the Pragfriedhof in his Stuttgart with a ceremony with great pomp which was attended by King William II of Württemberg (3).

Footnotes

1) The decision to portray the carabinieri can be explained by the propaganda will to keep up the image of the weapon, cracked by the repression of the strikes and, above all, by the execution of the sentences of the military tribunals.

2) The time is anticipated, between 5 and 6 in the morning. The action then takes place from a different angle; instead of barring its way, Morini fires at the car from behind. What is perplexing about this version is why the car didn't just accelerate to release.

3) The Supreme Command of the Royal Army resided in Udine until 27 October 1917 when it moved to Padua. Cadorna instead left at 15.30 for Treviso, in order to be closer to the operations in progress.

4) Although part of the Deutsches Reich from the 1871 the Württemberg maintained its monarch even if devoid of any sovereign power. Following the German defeat abdicò, like his Kaiser, in November 1918.

ITALIAN VERSION

After von Graevenitz's version we now compare ourselves with that of the other protagonist of this story: Sergeant Giuseppe Morini. We will see that in some respects they differ.

Giuseppe Morini was born in Civitavecchia the 23 March of 1891. Bersagliere already in the lever call, then remains in the plumed infantrymen. The facts find him sergeant in the III Battalion Bersaglieri cyclists. The cyclist departments were in all the armies selected troops, capable of great mobility like the cavalry, but of less vulnerability and cost of maintenance (the horses cost and magnate NdA). After the German breakthrough they were always at the forefront in countering the Germanic avant-gardes to allow the stragglers and the numerous fleeing civilians to retreat beyond the Tagliamento and then up to the Piave (4). The battles of the retreat were, until a few years ago and with some exceptions, always relegated if not silenced by the official historiography. Between that shameful "first" - Caporetto - and the heroic "after" - Piave - there seems to be only a chaotic and ignominious escape. The epos instead is in the middle. It is in the dozens of skirmishes, small counterattacks and stubborn defenses mostly implemented without coordination, at the level of the lower officers, for the sole desire not to give up land. If these battles were not there, it is unthinkable to believe that the retreat would succeed; the Third Army would have been crushed well before arriving at the Tagliamento and imagining after a Piave would have been pure science fiction. Citing them all is difficult, but beyond the heroic sacrifice of the Genoa cavalry and the lanceri of Novara in Pozzuolo del Friuli (the Italian Balaklava NdA) (5) the defense of Udine, the defense of Monte di Ragogna and that of Monte Festa deserve mention. The Bersaglieri cyclists, like the bold ones, lent themselves perfectly to these roles of containment.

The dawn of the 25 sees then start the III Battalion at a time of San Vito al Tagliamento, from the base of Cassola. Arrived at their destination in the late afternoon of the 27, they go to depend on the 22 cavalry division. The new objective assigned to him is to explore the Cividale-Udine artery, to realize the actual moves of the Germans, whose advance director is mostly unknown to the upper command. Also in this the encounter with the enemy is caused by a misunderstanding. Just out of Udine cyclists come across an unusual quartet: two Italian generals who with some artillerymen try to place a cannon. The senior officers assure the commander of the department, Major Carlo Tosti, that a little further ahead Italian troops have set up a provisional defensive line. Heartened by the news and convinced that they are heading towards friendly troops, the Bersaglieri maintain the marching disposition. However, in the vicinity of San Gottardo, the head company is subjected to the firing fire of a German patrol hidden in a house. Cyclists abandon the means and take the attack provisions, but in the momentary chaos of surprise (and the fall from the NdA bicycles) the avant-garde commander is captured. Captain Del Re had pushed forward to make contact with the Italian lines and therefore at the moment of the attack he is temporarily isolated by his men. The Germans take advantage of it quickly and capture the officer. Italians try to respond to the fire, but the enemy, outnumbered, decides to abandon the battle. So he took note of the presence of enemy avant-gardes, the second in charge Lieutenant Mari places his men on the defensive line, ordering Sergeant Morini to position himself a little further ahead, at the road curve, so as to control whoever arrived from the East. Morini is in the company of Corporal Schiesari and three other Bersaglieri who are deployed in a sheltered house, so as to have a wide view of the surrounding area. Instead he goes into the streets to monitor the entrance of the improvised cornerstone. It's about 8 in the morning, General von Berrer is starting from Azzida right now. After about thirty minutes, Morini sees a car coming from Cividale. The first impression of the sergeant is that they are official allies; he is also about to make a military salute when he realizes that they are not waving on the bonnet the Union Jack or the Tricolor, but the unmistakable colors of the Reichskriegsflagge. Two seconds, enough time to recover from the surprise, and the sergeant places himself in the middle of the street, pointing his rifle as he shouts to his men to go down the street. While the car attempts an inversion, Morini's 91 explodes three hits. The car is stopped; they come out chaufferurs while an officer, gun in hand, fires at the young bersagliere. Start a lively exchange of bullets between the two until the Morini, belly on the ground, is having to recharge. The other takes the opportunity to disengage from the clash and disappears behind a cottage. Replaced the charger the bersagliere directs a couple of shots to the only targets still in sight; the two drivers. One falls to the ground but, although wounded, gets up and continues the flight. The officer remains. He finds it hidden and tending to panic behind the edge of a latrine. However, the Italian view has an invigorating effect on German; the fear disappears leaving the place to anger. After an empty blow he starts a violent body to body that sees the bersagliere disarm and then immobilize his opponent. At this point the reinforcements have arrived and it is then, looking at the car, that the Italians are aware of another occupant, much more precious than the newly captured Lieutenant von Graevenitz. An impeccable old man in the imperial uniform returns to the curious an off and vitreous look, while the blood already begins to coagulate from the wound in the forehead. The documents immediately return the identity, but the surprise of the Italians is even greater when in the pockets of the coat of the general find the cards in which are marked the lines of attack of the Austro-German columns. It is interesting to note how in the latter the limit for the German avant-gardes is represented by the Tagliamento river, not by the Piave; this confirms that the scope of the objectives was smaller and this underestimation of the effectiveness of the operation is to be considered as a contributory factor in the lack of annihilation of the Italian forces. It can be said that Caporetto amazed both. The ones paralyzed by an unprecedented breakthrough and others by their own rapid advancement. This is not disputed when one considers that the war of position had accustomed both belligerents to measure successes in a few kilometers, sometimes even in meters; certainly not 150 kilometers in less than three weeks.

Once the corpses of their belongings are stripped, the Bersaglieri deliver the prisoner to a nearby carabinieri. They will be the first to inform the General Staff of what happened. And it is legitimate to suppose that for this reason they will be considered the first responsible. Meanwhile, the abandoned car is still a source of trouble. Having found the excellent condition, Captain Prina took possession of it but, after a few meters, he came across a group of fellow soldiers who, seeing the enemy insignia, opened fire on him. The car ends off-road and is definitely kaput; we can only imagine the pitfall of insults that the unharmed captain will have reserved for his subordinates. The lieutenant prisoner also attends the tragicomic scene, but the distance prevents him from seeing the course clearly; in fact, in his testimony he will bring back the heel to the driver's expertise. Ability to drive apart, there are other points on which the statement of von Graevenitz deviates from that of Morini. First of all the number of Italian soldiers: only himself for the bersagliere, well 60 according to the lieutenant. The Italian version then lacks the reference to Captain Boeszoermeny and the general's death seems to have occurred in two successive moments: on the stroke in one case, after a first wound in the other.

Let's try to do some clarity. Of Boeszoermeny's death there can be no doubt, given his tomb in the cemetery of Cividale, next to that of his superior. There are two cases: o Morini omits the episode not considering it relevant, or taking into account the driving rain and the combat fights, he has not simply realized. Von Graevenitz himself tells us that the captain's body fell into a ditch and then it is plausible to believe that the Italians did not notice it. Taking into account that they will shortly turn back to Udine, one can not certainly blame them for their lack of investigation. Even the general's wounds do not seem to be problematic. He may well have been wounded before and still had time to shout orders before being shot to death. Surely the Morini, finding him with a wound in front in perfect view will not be sure to put the autopsy of the patient. The number of soldiers present, on the other hand, is the most conspicuously different element.

We can immediately say that the German version presents some perplexities. The number of strokes reported by the machine appears ridiculously low. Only seventeen holes, by the same German admission, which are then added to the blows of friendly fire received by Captain Prani. Now, it becomes difficult to believe that sixty men who shoot on a stationary machine a few steps away are so inaccurate. It is also unlikely that any of the occupants came out alive under such fire. Finally, the same provision of the company that, according to Italian sources, is deployed in depth of a few hundred meters with Morini as an advanced tip. This deployment is tactically more credible than a mass of men on the streets of San Gottardo. For these reasons the version of the bersagliere appears more realistic.

As to why von Graevenitz has testified otherwise, we can only put forward hypotheses: the first is to safeguard the honor of the military, who certainly prefers to say that he has been overwhelmed by an unequal battle; the second, in my opinion preferable, is that the testimony is affected by time and the lack of an overview at the moment of the facts. He, unlike Morini, made it a few years after the end of the war and it is not difficult to assume that in the conciliation of events he believed he was facing a greater number of adversaries; the same that at the time of his capture had now arrived on the spot.

Footnotes

4) About the 300.000 were the stragglers and 400.000 the refugees.

5) The Battle of Balacklava took place on the 25 October 1854, as part of the Crimean War. The episode that made her famous was The Charge of the Light Brigade in which the English cavalry frontally loaded the Russian artillery. The term is used here as a synonym for heroic and suicidal cavalry.

REFERENCES:

Gaspari Paolo The battle of the captains 2005 Gaspari publisher.

Seccia Giorgio Udine, 28 October 1917 . From the 38-45 page of the monthly magazine Military History, volume n. 223 of April 2012 published by Albertelli Edizioni Speciali Srl

Corriere della Sera Historical Archive. Article 19 November 1917.

(photo: web)