It was April '89, and I was in Rome in the AUC battalion and volunteers at the Giuseppe Perotti barracks, headquarters of the Transmission School now known as SCUTI. At the end of a few weeks of training and about to return to the assignment department, an officer accompanied me to a room located in the auditorium building. Inside there was an interesting video library on Army professions and behavior on duty or during the guards. I started playing several videos on the VCR, including those on vehicle driving training; in particular I still remember a blue Fiat 128 with a voice in the background explaining to change in two strokes. A bit like the training videos produced by the US Army, certain maneuvers were clearly explained to safeguard the safety and mechanical integrity of the vehicle. Standards also shared by the guidelines of civil driving schools when, in order to obtain a B license, it was necessary to have some knowledge on the mechanics of the vehicle.

Although technology has entered the military vehicles with a straight leg, it is also true that within the Armed Forces and in particular in the Army, that concept of selective school which is not satisfied with carelessness, expecting to repeat in particular the more complex maneuvers, even if used very rarely.

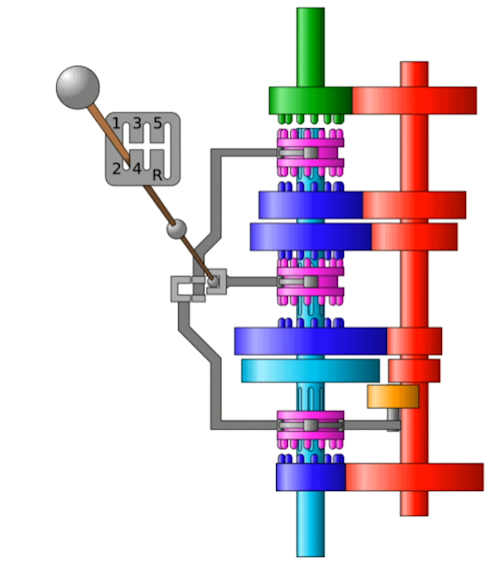

Gearbox and pedals, the "double"

The double disengagement of the transmission more commonly called "shotgun", was the basis that distinguished a military license from a civil one. An exercise in skill and sensitivity to be performed quickly by listening to the sound of the engine and the colorful expressions of the instructor, especially when scratching with the reducer of a CM 52 or other unsynchronized means.

What was the shotgun for? Basically to approach two speeds, that of the vehicle and that of the engine, thus allowing the engagement of the gears without synchronizers.

What was the shotgun for? Basically to approach two speeds, that of the vehicle and that of the engine, thus allowing the engagement of the gears without synchronizers.

In the gearbox there are three shafts, one packaging which takes the motion from the clutch assembly, a packaging aligned to the primary and connected to transmission and wheels, and a shaft auxiliary which acts as a bridge between the two by generating relationships. A very robust and absolutely reliable scheme, but not many are actually using it well, especially those who mistakenly travel through stretches with the clutch down to override the correct procedures. The double disengagement, moreover well explained by the videos of the barracks, was not only used for climbing, but also for each change of gear to climb, in this case in two stages and without accelerating.

The climbing procedure: Depress the clutch and shift the gear into neutral, release the clutch pedal, accelerate proportionally to the vehicle speed with the lower gear engaged, depress the clutch again and downshift.

The procedure changed to go up: same procedure without accelerated.

When the toe and heel maneuver was required, many went into crisis, especially in fast driving courses with the Alfetta. In fact, only with certain pedals is it possible to act with the tip of the foot on the brake and the heel on the accelerator. In some configurations of pedals this union is almost impossible, therefore it is necessary to anticipate the braking (for example in heavy vehicles), or (but don't do it) learn from the rally school of Scandinavian drivers, notoriously good at braking with their left foot.

Often in sports driving, it is more congenial to use the inner side of the shoe to brake and the other half to tap the accelerator. A technique that is valid both for braking brace and for stabilizing the vehicle when cornering, controlling pitch and trajectory. It takes sensitivity though.

Don't use force

In particular on heavy vehicles, it may happen that the gear lever gets stuck or faces a bit of resistance. Here, this is most often due to the work of the synchronizer, which is accelerating or slowing down the rotation of a shaft to get closer to that of the gear to be engaged, or to a tooth that pushes out of its seat.

To limit jamming, often due to the inertia of the heavy gear trains, the double disengagement or at least a slight pressure and release of the clutch can soften the shifting. Acting with force, in addition to deforming bushings and levers, consumes the friction cones of the synchronizers.

Sensors, robotic and automatic transmissions

The driver's skill potential has shifted towards attention to the interactive and control systems found on modern vehicles. In reality in modern 4x4s there is a "solver button", perhaps for ice or mud, a condition that in itself loosens the information that the vehicle and road transmit to the driver, leaving common sense and experience the sense of the limit. For this reason, the army annually organizes intensive driving courses on rough terrain.

Even in the professional and military fields, the difference between elderly and young drivers is felt and one of the most widespread habits has become the use of navigators instead of faithful road maps. The fact is that the space freed up by the technological development of the vehicles has been filled with updates and tactical protocols, such as to nickname the driver of an armored tactical truck / vehicle “pilot”.

The proliferation of automatic transmissions and sensors is therefore changing our relationship with the car, probably sweetening it. But in the barracks what method is used for training?

Identifying skills and predisposition are the first step, and here a man or a woman makes no difference if at the base there is the vocation to drive. The first skimming takes place by observing the operation with synchronized manual gearbox of ACM90 or ACTL where the instructor, strong in “old school” traditions, can also suggest a hint of a double shot. Then we move on to long periods of quality confirmation with the most modern and automatic means.

The robotic or automated gearboxes set up on the tactical are basically redesigned manuals that to a certain extent automatically and faithfully repeat what we did on the good old CM52.

The automatic with torque converter (the hydraulics), are generally sweet and reliable with a very different scheme than the manual gearbox and composed of planetary gears and clutch packs, once activated by the centrifugal movement of a valve drawer, today instead of sensors.

The increasingly tested and reliable technology is therefore a concept also assimilated in the management of modern tactics, where the experience of the "old school" will certainly provide operators with added value in the most critical situations.

Photo: web