The Indo-Pacific in its broader maritime, territorial, demographic and economic context certainly represents, in today's world reality, the part of the world on which the attention of the international community is most concentrated. It is a vast geographical area, which includes thousands of kilometers of Asian coast and two important peninsulas (Korea and Vietnam), which includes the multitude of islands that stretch from the Indian Ocean to the large archipelagos that arise near the coasts (Japan , Philippines, Indonesia), to reach the most distant and substantial continental structures (New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand), and the tiny islands of Micronesia or the Hawaiian Islands and the American coast, from Canada to Chile.

An immense region which today is going through a period of intense evolutionary ferment and which is looking for new equilibriums, capable of taking into account its complex and constantly changing reality. A geopolitical area characterized by a high rate of growth, which has determined the shift of the center of gravity of the world economy, but also by a notable lack of homogeneity, which translates into very diversified and, not infrequently, conflicting interests. This has implications on the level of international security and stability because, in a context of marked interdependence such as today, the events that unfold in this vast area have the capacity to influence the rest of the world as well.

In this context, the dynamic role and decisive contribution of China clearly emerges, which alone contributes about 30% to world growth and is the hegemonic power of the area, also causing important effects on global strategic balances. It is therefore easy to understand how the new and more assertive Chinese policy, which translates both into the inflexibility on the issues of Taiwan and Tibet and into the decisive territorial claims and maritime borders, can cause concern especially in the most exposed neighbors, from Southeast Asia. to Japan.

If we then consider that international relations in Asia are generally based on suspicion and a widespread lack of mutual trust, a residue of historical unresolved conflicts and atavistic rivalries, we understand how the whole area is characterized by a widespread fragility of the delicate balances at the time. in time with difficulty achieved1 and how justified such restlessness appears. Unlike the European theater, in fact, a major war between large countries is far from unthinkable on this continent, the arena of the major disputes in the contemporary world. Just think of the persistent tensions between India and Pakistan, between India and China, between the two Koreas and between China and Taiwan (with the United States in the background), the dispute over the submarine resources of the South China Sea, which affects eight countries, the claims on the uninhabited Senkaku Islands (or Diaoyu, as the Chinese call them) disputed with Japan, on the Paracelsus Islands, disputed with Vietnam, and on the islands of the Spratly archipelago, disputed by Vietnam, the Philippines, China, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei, but transformed by China into a military base with airstrips and anti-ship missiles. If we also consider some “minor” disputes, we arrive at more than twenty potential causes of conflict, which almost always see China present, in one way or another. On the other hand, when it comes to the People's Republic of China, it must be remembered that among its main declared objectives are the reunification of China (with clear reference to Taiwan) and the reaffirmation of its "historical rights" over much of the South China Sea. . A clear indication of its expansionist aims and a clear warning to the other coastal countries.

If we then consider that international relations in Asia are generally based on suspicion and a widespread lack of mutual trust, a residue of historical unresolved conflicts and atavistic rivalries, we understand how the whole area is characterized by a widespread fragility of the delicate balances at the time. in time with difficulty achieved1 and how justified such restlessness appears. Unlike the European theater, in fact, a major war between large countries is far from unthinkable on this continent, the arena of the major disputes in the contemporary world. Just think of the persistent tensions between India and Pakistan, between India and China, between the two Koreas and between China and Taiwan (with the United States in the background), the dispute over the submarine resources of the South China Sea, which affects eight countries, the claims on the uninhabited Senkaku Islands (or Diaoyu, as the Chinese call them) disputed with Japan, on the Paracelsus Islands, disputed with Vietnam, and on the islands of the Spratly archipelago, disputed by Vietnam, the Philippines, China, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei, but transformed by China into a military base with airstrips and anti-ship missiles. If we also consider some “minor” disputes, we arrive at more than twenty potential causes of conflict, which almost always see China present, in one way or another. On the other hand, when it comes to the People's Republic of China, it must be remembered that among its main declared objectives are the reunification of China (with clear reference to Taiwan) and the reaffirmation of its "historical rights" over much of the South China Sea. . A clear indication of its expansionist aims and a clear warning to the other coastal countries.

It should also be remembered that Asia is the area of the world where the greatest quantity of weapons is present. Defense spending has in fact increased enormously in the last twenty years, despite widespread economic and, today, health crises. According to it Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) six countries in the area (India, China, Australia, Pakistan, Vietnam and South Korea) account for about 50% of the global growth in arms imports. In this context, China is the country that is spending more than anyone in the world for the acquisition of armament material from abroad. Chinese military spending is so high overall that, according to some commentators, China ranks second in the world, behind only Washington.

It should also be remembered that Asia is the area of the world where the greatest quantity of weapons is present. Defense spending has in fact increased enormously in the last twenty years, despite widespread economic and, today, health crises. According to it Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) six countries in the area (India, China, Australia, Pakistan, Vietnam and South Korea) account for about 50% of the global growth in arms imports. In this context, China is the country that is spending more than anyone in the world for the acquisition of armament material from abroad. Chinese military spending is so high overall that, according to some commentators, China ranks second in the world, behind only Washington.

The same Institute also underlines the presence in that area of six countries equipped with nuclear weapons (China 320, India 150, Russia 6.375, United States 5.800, Pakistan 160 and North Korea 30-40), to which are added the declared impulses in the same direction of Japan and South Korea.

The main regional associations

Increasing the international community's concerns about the stability of the area is the fact that in Asia there are no collective security organizations similar to NATO, nor multilateral treaties for the reduction of tensions and armaments, all elements that have lightened the latest phases of the Cold War and were decisive, in part, for its overcoming and for the construction of an environment of confidence building. On the other hand, there are a certain number of predominantly economic and fundamentally weak sub-regional associations, organizations and symposia, where essentially national interests almost always end up prevailing, so much so that up to now they have proved to be inadequate venues for the settlement of the various disputes between Asian states and which appear not to have the necessary tools to settle disputes in the event that the words were to pass to a more muscular confrontation.

The best known of these is theAssociation of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), which includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. It is an association of states founded in 1967 essentially with the political functions of containing communist influences. Although it also played a role in the region's equilibrium (common security, arms limitation, conflict resolution), the presence of widely differing views on political and government processes (including practices in areas such as suffrage and representation politics), the range of types of government (ranging from democracy to the people's republic), the different economic approaches (from capitalism to socialism) have essentially made meetings on strategic issues relating to security fruitless. This has meant that, over time, it has lost the original anti-communist connotation which, for many years, had been its main reason for being, and has moved on to deal mainly with economic-commercial aspects, a sector in which it proved less difficult to reach an effective compromise between the various positions. Other separate groups allow China, Japan and South Korea to interact with ASEAN.

The best known of these is theAssociation of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), which includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. It is an association of states founded in 1967 essentially with the political functions of containing communist influences. Although it also played a role in the region's equilibrium (common security, arms limitation, conflict resolution), the presence of widely differing views on political and government processes (including practices in areas such as suffrage and representation politics), the range of types of government (ranging from democracy to the people's republic), the different economic approaches (from capitalism to socialism) have essentially made meetings on strategic issues relating to security fruitless. This has meant that, over time, it has lost the original anti-communist connotation which, for many years, had been its main reason for being, and has moved on to deal mainly with economic-commercial aspects, a sector in which it proved less difficult to reach an effective compromise between the various positions. Other separate groups allow China, Japan and South Korea to interact with ASEAN.

We then have the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which includes China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, to get to the South Asian regional cooperation group, whose members are Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. China, the United States, Japan, Iran and the European Union participate as observers.

Finally, after eight years of negotiations, November 15 was formalized Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes the ten economies of ASEAN plus China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and Australia. An agreement reached precisely as a result of a growing global trend towards protectionism, mainly fueled byAmerica first of the Trump administration, which gave the participating countries the rationale for starting this free trade area.

Finally, after eight years of negotiations, November 15 was formalized Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes the ten economies of ASEAN plus China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and Australia. An agreement reached precisely as a result of a growing global trend towards protectionism, mainly fueled byAmerica first of the Trump administration, which gave the participating countries the rationale for starting this free trade area.

Nonetheless, although these are organizations that boast of representing billions of people, they have not even contributed to clarifying how to manage disputes over the dozens of islets and maritime areas of the South China Sea. They seem, in fact, structurally unable to mediate in the event of a conflict, for example, between India and Pakistan or between China and the United States for Taiwan. Excellent stage when it comes to economic cooperation, media appearances, symbolic exercises and fleeting handshakes, appear to be devoid of any real value for maintaining or restoring peace in the event that conflicts involve large and important states. However, their existence allows China to strengthen its economic and political sphere of influence, increasing its ability to compete with the United States in the area. India, the only economy that could have balanced the Chinese giant, is not part of the latest agreement by choice of New Delhi, which withdrew from negotiations in 2019, definitively wiping out the idea that China can be isolated, in a context of global economy.

Relations with the main countries

As regards the main disputes with other Asian countries, which I have already referred to in my previous articles, these see the maritime area that bathes the easternmost coasts of Asia at the center of the disputes, both for national sovereignty issues and, above all, for reasons of exploitation of the important marine resources present.

Furthermore, after the China Sea, the Indian Ocean is also taking shape as a disputed space by Beijing. In this context, as Peter Frankopan writes, "... in the summer of 2016 Pakistan announced that it would spend five billion dollars on the purchase of eight diesel-electric attack submarines from China ..."2.

Furthermore, after the China Sea, the Indian Ocean is also taking shape as a disputed space by Beijing. In this context, as Peter Frankopan writes, "... in the summer of 2016 Pakistan announced that it would spend five billion dollars on the purchase of eight diesel-electric attack submarines from China ..."2.

These political-economic relations in terms of naval armaments have caused apprehension in India, notoriously already opposed to both Pakistan and China for territorial issues. Not only that, the supply of naval capabilities to Pakistan gives China one more reason to "enter" the Indian Ocean, highlighting its ambitions in that area as well. It is no coincidence, in fact, that they have been in the area for some years now "... always present at least eight Chinese warships at a time (on one occasion there were even fourteen on patrol) ...", officially for anti-piracy operations. A presence that worries New Delhi, also due to the increasingly aggressive attitude shown by the Chinese crews. A growing tension that in February 2018 led Beijing to denounce the threats suffered by some Chinese ships, against which some Indian units would have addressed a warning shot. The complaint was immediately denied by the Indian authorities. In addition, in March 2018, some joint exercises (Milan 2018) carried out in the southern part of the Bay of Bengal (Andaman and Nicobar Islands), with the participation of ships from 23 countries, including India, Australia, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Oman and Cambodia, have unnerved the Chinese authorities to this point to having issued fiery statements, underlining how such actions could have carried the potential for conflict from land to sea.

A worrying situation which, as we will see later, has convinced New Delhi to abandon the traditional political and military “non-alignment”, making India take sides with the United States. In order to monitor the activity of passing Chinese submarines, India has, in the meantime, this year set up a network of hydrophones and magnetic anomaly detectors about 2.300 km long, between the island of Sumatra and archipelago of the already mentioned Andaman-Nicobar islands. The chain, a more modern version of the one used during the Cold War for detecting the movements of Russian submarines, will also be used by ASW aircraft for location by triangulation.

Japan, as mentioned, still sees the dispute with China in relation to the sovereignty over the uninhabited Senkaku islands (or Diaoyu, as the Chinese call them) claimed by Beijing on the basis of historical and geographical criteria. Without going into the legal merits of the matter, it is enough to remember that Tokyo would like the boundary of its respective Exclusive Economic Zones to be identified with the median line of the maritime borders, while Beijing states that its EEZ should reach the limit of the continental shelf (Okinawa channel ). In a nutshell, this is an overlap of about 81.000 square nautical miles of sea full of fish and with discrete reserves of hydrocarbons. Within this area are the Senkaku Islands. In November 2013, China unilaterally decided to establish a air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the disputed islands, thus reaffirming its position on sovereignty over the archipelago. This area completely overlaps a similar airspace established by Japan in 1968 to protect the islands from possible air raids. In addition, in order to highlight the alleged abandonment of those islands by the Japanese, China has recently raised the level of naval presence around the contested area and within its contiguous waters. On one occasion a Chinese unit was pursuing a Japanese fishing boat, and a Coast Guard unit was forced to intervene in defense of their compatriots. Japanese anxieties are therefore anything but unreasonable and unfounded.

Japan appears, however, to have the economic and technological resources to try to respond to these challenges by developing long-range missile capabilities and naval projection capabilities, complemented by credible anti-missile defense.

However, there are those who fear that a politically more active and militarily significant Japan could pose a threat to the balance of the area. In particular, the growth of the Japanese fleet is still viewed with some suspicion. Whether it is a legacy of the well-known events of the last century or not, the anti-Japanese hostility in Asia is still deep and deeply rooted, even if the profound mutation wrought by that country after the Second World War, and the enormous diplomatic work developed for the complete rehabilitation of its historical and geopolitical identity, they seem to have shown that the country should have understood how to control its sensitivity on issues that concern its specificity. A theme that in the past led him to ruinous choices.

After having been worn down for a long time by the dilemma of whether to aim for regionalization, cultivating deeper relations with China (until the early nineties defined as the only architrave of Japanese diplomacy) or whether to follow the American "wheel", assuming greater political responsibilities in the area, therefore, it seems that the aggressive Chinese attitude has definitively tipped Tokyo's balance in favor of the second hypothesis. This led to an increase in its overall arsenal, with a consequent significant increase in defense spending. After having extended its aforementioned self-defense area for some time, Japan has therefore moved on to building a modern deep-sea fleet, which involves the need for air and naval coverage. The aircraft carriers are not there yet, but it is not certain that they will be long in arriving.

Russia, a power that is slowly reorganizing and modernizing its fleet (there are about 20 ships set up in 2020 alone) after the serious crisis suffered at the end of the last century, has seen a gradual improvement of its complex relations with China. Favored by the end of the race for primacy in the Communist world, this improved relations allowed Beijing to access the technology necessary to begin the development of a modern and competitive fleet and Moscow to raise over nine billion euros in naval armament sales. Its ongoing transition, however, is reflected in its overall involvement in Asia and its fleet projection in the Pacific.

Nonetheless, despite the downsizing of its commitment and the temporary forced abandonment of the primitive objectives of expanding its influence, Moscow does not intend to give up its role as an important Asian and Pacific country.

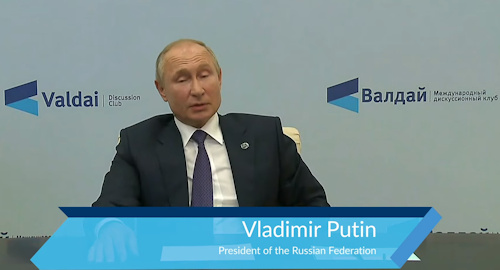

With a total of about 60 surface naval units and 20 submarines (one component, the underwater one, still powerful and fearsome today), Russia continues, therefore, to assiduously take care of international relations on that chessboard, striving to maintain the traditional ones and improve any deteriorated ones. In this context, President Putin, during the recent annual meeting of Valdai discussion club (Moscow 20-22 October 2020), a sort of Russian Davos inaugurated in 2004, has declared himself a possibility regarding a possible military partnership between Russia and China, whose cooperation in the naval sector could serve to balance the naval power of the United States and allies in the area.

As for the United States, no administration questions the interest in Asia and the Pacific, generally shared by public opinion. In this context, despite Washington is going through a period of general tendency to reduce international involvement, the level of commitment (including military) in the area has not undergone any kind of downsizing, indeed. In spite of the recent isolationist inspirations, Washington is aware of its own military supremacy, overwhelming and constantly updated, and intends to continue to influence wherever the dangers of conflict and upheaval appear, primarily Indo-Pacific. But maintaining a credible and competitive (even from a numerical point of view) naval presence has a price that the US cannot sustain for long on its own.

Hence, pending cooperation, for example, from NATO allies (Italy? France? United Kingdom? Germany?) Who were asked to be willing to be present even in those distant waters, an axis has been formed that seeks to stem the growing Chinese maritime presence in the Indo-Pacific area, the “Quad”. The United States, Australia, India and Japan have, in fact, started a naval collaboration which, for some observers, could represent the core of an Asian NATO. Launched several years ago by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, this security dialogue initiative had never actually taken off, in order not to damage relations with Beijing. Only the recent worsening of regional maritime tensions, and the more aggressive posture of the Chinese, has allowed to give a decisive boost to its realization. A quadrilateral that is therefore proposed as a collaboration for the strategic containment of China on the thousands of nautical miles represented by the Indo-Pacific theater. An initiative that began with a joint naval exercise, a clear message whispered directly to the Chinese ear.

Hence, pending cooperation, for example, from NATO allies (Italy? France? United Kingdom? Germany?) Who were asked to be willing to be present even in those distant waters, an axis has been formed that seeks to stem the growing Chinese maritime presence in the Indo-Pacific area, the “Quad”. The United States, Australia, India and Japan have, in fact, started a naval collaboration which, for some observers, could represent the core of an Asian NATO. Launched several years ago by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, this security dialogue initiative had never actually taken off, in order not to damage relations with Beijing. Only the recent worsening of regional maritime tensions, and the more aggressive posture of the Chinese, has allowed to give a decisive boost to its realization. A quadrilateral that is therefore proposed as a collaboration for the strategic containment of China on the thousands of nautical miles represented by the Indo-Pacific theater. An initiative that began with a joint naval exercise, a clear message whispered directly to the Chinese ear.

Conclusions

The creation of a network of alliances alone does not seem, however, sufficient to form a defense against the growing Chinese ambitions and presence in the Indo-Pacific area. Consequently, spending in the defense sector, especially with regard to maritime capabilities, has been gradually increasing throughout Southeast Asia and Oceania in recent years. Behind China, therefore, the Asian countries that fear its aggression the most, or that have ongoing disputes, have engaged in a race for naval growth, with Japan and India emerging above all for economic commitment and quality of the armament . Furthermore, in February 2019, Australia approved the expenditure of approximately 36 billion dollars for the purchase of 12 new attack submarines, which will be built by France and assembled in Adelaide. This is Australia's largest peacetime defense procurement and delivery is expected to take place in 2030. However, to be fair, in January this year, problems arose regarding Australia's participation in the project, with the 'CEO of the French company who questioned Australia's ability to effectively meet its commitments. Nevertheless, the political will is clear and the path well determined, so much so that on October 27 the Federal Government, following the growing strategic uncertainty in the home area, announced that from 2021 it will interrupt its thirty-year naval presence in the Middle Eastern waters.

The countries bordering the Indo-Pacific, enormously differentiated by political, institutional, social, economic structure and military capabilities are moving in an increasingly complex and dynamic international security context, where competition for the exploitation of marine resources is now extreme. . A differentiation that also manifests itself in the heterogeneity of perceptions they have about the overall sense of security produced in the area by the permanence of the US fleet. Some countries, in fact, believe that the American presence has the double value of a deterrent but also a potential reason for escalation with China. This involves a race for strategic positioning that involves everyone. Indonesia, for example, on 22 October denied permission for US spy planes to land on its territory, so as not to hurt Chinese susceptibility and remain equidistant between the two contenders.

The countries bordering the Indo-Pacific, enormously differentiated by political, institutional, social, economic structure and military capabilities are moving in an increasingly complex and dynamic international security context, where competition for the exploitation of marine resources is now extreme. . A differentiation that also manifests itself in the heterogeneity of perceptions they have about the overall sense of security produced in the area by the permanence of the US fleet. Some countries, in fact, believe that the American presence has the double value of a deterrent but also a potential reason for escalation with China. This involves a race for strategic positioning that involves everyone. Indonesia, for example, on 22 October denied permission for US spy planes to land on its territory, so as not to hurt Chinese susceptibility and remain equidistant between the two contenders.

The medium-term future of the world depends on what will happen in the next decade in this immense chessboard, which has a direct influence on about two thirds of the world population and on over half of global production.

However, even if at the moment China, a hegemonic power in the area, for its own reasons does not appear willing to clash but, on the contrary, to keep the peace, other governments in the region could be motivated by different intentions, and be induced to carry out earlier or then aggressive actions, perhaps precisely in the area that is at the center of Chinese interests, the South China Sea.

It is therefore an unstable and dangerous reality. It does not take long to understand how any provocation, real or perceived, intentional or not, can easily cause a disastrous escalation with virtually devastating effects, given that in that area more than one potential player, on both sides, is equipped with nuclear weapons and that the fire could also spread to other areas of the world.

It has therefore become of global importance to avert the danger of possible unilateral decisions by introducing effective prevention mechanisms, such as those effectively tested during the Cold War, to prevent rivalries from escalating in that area of the world and to prevent any armed confrontations. add serious problems in a continent and a world that do not need them at all.

1 "Peace looks fragile in Asia”, By Paul Dibb, one of the foremost military experts of the Pacific Rim and director of the Center for Strategic Studies of Camberra, onInternational Herald Tribune June 19, 2002 (article also taken from New York Times)

2 Peter Frankopan, The new silk routes, Mondadori, 2019, p. 104

Photo: MoD People's Republic of China / ASEAN / DFAT / Indian Navy / JMSDF / Valdai Club Foundation / web / US Navy