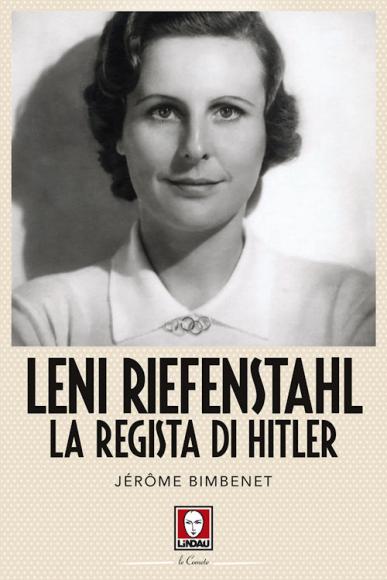

Jérôme Bimbenet

Ed. Lindau

pagg.376

A new passionate and exciting biography signed by the cinema historian Jérôme Bimbenet, Leni Riefenstahl. Hitler's director, reconstructs the dramatic story, the result of extensive research, one of the most multi-faceted and brilliant artistic personalities, but also more controversial of the twentieth century, disappeared in the hundred-year-old 2003.

The name of Leni Riefenstahl remains inextricably linked to the figure of Adolf Hitler and his relations of collaboration with the Nazi regime. But the director, in his memoirs (Narrow in Time - History of my life), he denies any propaganda responsibility, denies his cult of the leader of National Socialism, admitting only that he has lent his talents. "For her they only counted art and aesthetics. And it is precisely this reproach that disfigures his memory and obscures his future glory"(P. 355).

Bertha Amalie "Leni" Riefensthal was born in Berlin on 22 August 1902 in a German upper class bourgeois family. After studying painting he dedicated himself to dance, but in the 1923 a knee injury forced her to give it up. In the mid-1920s he made his debut as an actress, playing a series of films by Arnold Fanck, the inventor of mountain films, Bergfilme, a very popular film genre in Weimar Germany. He then passes on the advice and encouragement of the great filmmaker Gorg W. Pabst, behind the camera to direct in the 1932 Das Blaue Licht (The beautiful damn - the blue light), also written and interpreted by her.

But the turning point for his career comes with the rise to power of the Nazis. Leni Riefenstahl was not a member of the National Socialist Party and never took the card, nor had she expressed any interest in Hitler himself, at least until February of the 1932, when he attended one of his rallies at Sportpalast in Berlin. It is an electrocution: "in the moment in which [Hitler] spoke, I found myself amazed in an astonishing way by an almost apocalyptic vision that would no longer leave me [...]. I felt paralyzed [...] his speech exercised a real fascination in me". The emotion is so strong that it pushes Leni Riefenstahl to write a letter to express his admiration and his desire to know him personally. Hitler, who has seen all his films and is fascinated, in turn, by the grace and beauty of the artist, fulfills his desire and invites her to spend a day together. During the meeting Hitler tries to court her, but she withdraws. A "paradoxical and surprising" reaction, that of Leni, that "he would have rejected Hitler's advances, while he had done everything to find himself alone in his company"(P.112).

Hitler promises: "When we are in power, she will make films for me". After the first meeting in May 1932, many others followed, until the last one, in March 1944, in the Berghof, the mountain chalet of Hitler onObersalzberg.

The meeting with Hitler changes his destiny. As soon as Hitler comes to power, Leni Riefenstahl becomes the undisputed star of the film of the regime despite the hostility, according to him, by Joseph Goebbels, the powerful minister of Propaganda. "But the 'war' between Goebbels and the filmmaker was above all a post-Nazi invention to erase the complicity of Leni with the Nazis"(P.118).

The Führer of Germany entrusts her with the task of making three documentaries on the Party Day (Reichsparteitag), from the 1933 to the 1935, of which the most famous is rightly so Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the will) of the 1934. A document of exceptional beauty, which interprets the Führer, the highest the National Socialist hierarchy, and thousands of young people, elected as symbols of Aryan beauty. A work that exemplifies in a masterly way the National Socialist conception of the subordination of art to politics. Leni Riefenstahl does not make a documentary: "It builds the image of National Socialism". The Triumph of Will "It is not so much a film to the praise of the Nazi regime, as to the praise and glory of its leader, Adolf Hitler: 'There were only two themes there was Hitler and there was the people' summed up Leni Riefenstahl. The film is [...] built on a binary juxtaposition between the dehumanized mass and the individual, in which the leader rightly embodies the humanization of the mass, transference of the will of a people on one man "(p.149) .

For the film production the director has full autonomy and a budget and unlimited technical means, which allow her to experiment, new techniques and invent a "new cinematographic language": different angles of shooting, many long fields and close-ups, film cameras mounted on a braked ball for shooting from above, holes dug in front of the speakers for the shooting from below, a circular trench dug around Hitler's stage, so that the cameras mounted on trolleys turning around give the illusion of movement to a static scene.

The documentary receives the National State Award (Staatspreis) at the Berlin Film Festival and the Light Institute's Cup at the Venice Biennale.

"The film has become the archetype of propaganda films", and influences many great filmmakers, from Steven Spielberg to George Lucas, to Ridley Scott.

Two years later is the year of the Berlin Olympics. Hitler asks her to direct the official documentary of the Games. The Führer realizes the importance of such a film to spread the new image of National Socialist Germany in the world. Leni Riefensthal accepts and, once again, on the orders of Hitler, unlimited technical and financial means are granted to her. With his troupe of 170 collaborators, of which more than 30 operators, the director develops a further series of technological innovations: an underwater bell to film from below the plungers from the trampoline to the immersion in the pool and to the surfacing, cameras mounted on of an airship for panoramic views, a special telephoto lens to obtain perfect close-ups, holes on the sideline where the camera operators are placed to follow the filming from below, cameras mounted on trolleys, ralenty. And yet, to film the galloping riders, the operators are perched on the step of a car.

Olympia it takes two years for the assembly, in fact it comes out in the 1938. The result is truly extraordinary. Leni Riefensthal realizes a work of over three hours that is welcomed with enthusiasm by critics and public. A preview is presented at the 1937 International Exhibition in Paris. The documentary gets the German Film Grand Prix, the Mussolini Cup at the Venice International Film Festival and the Gold Medal of the International Olympic Committee.

It is the masterpiece that consecrates it worldwide.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the director follows German troops in Poland as a war correspondent. When in April of the 1945 the capitulation of the Third Reich is ominous imminent, it takes refuge in Mayerhofen, in Tyrol. Here the news reaches him of the death of Hitler. Leni Riefenstahl throws herself on the bed and cries all night.

With the fall of the Third Reich, the director is arrested by the Americans for collaboration with the Nazi regime and locked up for a few months in a criminal asylum. It is subsequently interned for three years in the denazification fields. All his possessions are confiscated. It is finally tried and acquitted by an allied court, because it is not involved in political activities. Silence falls on her. The hostility of the media, the systematic boycott of his work, the spread of incredible lies about his past, seem to relegate the Riefenstahl to the role of survivor. Rejected by producers, excluded from film reviews, attacked by critics, criminalized by some press, the German artist does not give up. Thus, after imprisonment, trials and discrimination, a new artistic life begins for Riefenstahl. In the 1960s he decided to leave Germany to travel to Africa, in southern Sudan, where he lived for eight months among the Nuba tribes. His reportages of rare beauty on this primitive population are published by specialized magazines of great diffusion. And a few years later she became passionate about underwater photography, fascinated by the underwater world of the Caribbean and Red Sea beds.

Leni Riefenstahl continues to shoot documentaries until the end of her days. His films are unsurpassable masterpieces that have made the history of cinema.

Without falling into the Manichaean trap of condemning or absolving, Bimbenet gives us back in this biography the complexity of an artist who throughout his long life has incessantly sought to capture beauty in all its expressions, fascinated by everything that releases life, strength, harmony, passing from the cult of the body and the vitality of the National Socialist aesthetic, to the wild corporeity of the masakin warriors, to the splendor of the uncontaminated seabed.

Giulio Festa