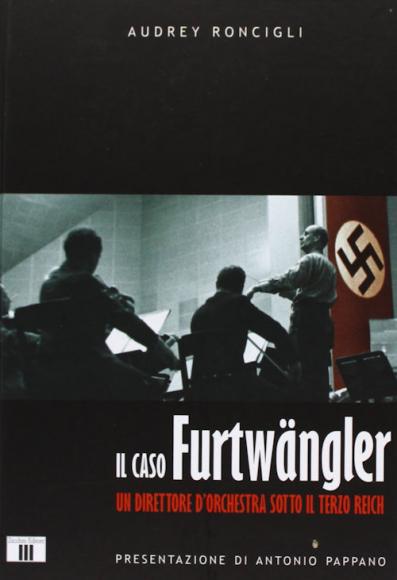

Audrey Roncigli

Ed. Zecchini, Varese 2013

pp. 306

"The Nazis made systematic and intensive use of music, establishing a dividing line between German music and non-German degenerate music." For this reason the ideological recovery of the great classics was a basis for the musical policy of the Third Reich; Beethoven, Bruckner and Wagner were reinterpreted in a heroic key and used for party celebrations. [...] In this perspective, Richard Wagner was considered the precursor and then the musical ambassador of the Third Reich. " But music, to be performed, needed musicians who were an integral part of the Reich's cultural policy. Among them were Richard Strass, Herbert Von Karajan, Arnold Schönberg.

"But certainly there is a musician who, more than others, allows us to investigate the relationships with the Nazi power and therefore remains the one on which the greatest doubts are condensed: the director Wilhelm Furtwängler."

Thus, the author, historian and musician, introduces us to the figure of this man who, still in recent times, is a source of discussion, so much so that his life is considered, precisely, by chance.

Born on January 23, 1886 in Berlin, Furtwängler, at the age of seven, decided to become a composer. Endowed with a great talent, he never attended a conservatory and at only 17 he composed his first symphony. On February 19, 1906 he conducted his first concert in Munich. In Luebeck, he later made his bones as director. He conducted in various cities including Mannheim, Vienna, Frankfurt, Rome to become director of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

Called by Winifred Wagner, daughter-in-law of the composer, Furtwängler was appointed musical director of the Bayreuth festival but, due to a contrast with Arturo Toscanini, he was acquitted from office in 1933, the year in which, on January 30, Adolf Hitler, close friend of the family Wagner became chancellor.

On April 7, the law on public employment resulted in the departure of Jewish-born directors en masse. "The Third Reich takes power over music in two moments: with the law of April 7, 1933 that removes Jews from state institutions and then decreeing the need to belong to the Reichmusikkammer (RMK, Reich Chamber of Music) created by Goebbels on November 15, 1933. "

Thus began the problems for Furtwängler who therefore found himself fighting a war on two fronts: against the Nazis at home and against his reputation as a Nazi abroad.

"I basically recognize only one dividing line: the one between quality art and art without quality." So wrote the master to Goebbels, when the law of April 7 was promulgated. And, as director of the Berliner Philarmoniker, "He makes it clear that if racial politics interferes with the life of his orchestra, he will step down from all positions."

Goebbels explicitly asked him to fire the Jewish musicians of the orchestra. On December 4, 1934 the master resigned from all his official duties, but gave up emigrating. "On December 17, 1937 Goebbels issued a law banning the recording and trading of records by Jewish composers and performers." Furtwängler, after the invasion of Poland by the Reich, refused to perform in the occupied territories.

In 1943, after the German surrender in Stalingrad, the Reich privileged war efforts over cultural issues, therefore all musicians were asked to participate in the war. "Many are canceled from military service and sent to the front." Furtwängler, however, was part of a special list containing personnel to be protected at all costs as considered "Immense capital for the nation."

After July 20, 1944, the day of the failed attack on Hitler, things changed for the Maestro, as his name was included in the list of alleged culprits since he would have been aware of the Valkyrie operation and, towards him, at the At the beginning of February 1945, Himmler signed an arrest warrant, an arrest from which he managed to escape by fleeing to Switzerland.

After Hitler's death on April 30, 1945, his name was also included in the blacklist of the Allies and a process of denazification started against him.

He was tried in Berlin with a sentence of April 1, 1947, which declared him "follower". His concert activity lasted until his death on November 30, 1954.

“Wasn't Furtwängler anti-Semitic in the Nazi sense of the word, but rather a nationalist spirit and protector of German values? It doesn't matter much what position Furtwängler wants to attribute to the Jewish question in itself, but what historically has value is to study its behavior and, above all, the consequences in the temporal context. So with his statements, Furtwängler raises very strong doubts in Goebbels and Göring: doubts that are heightened with his actions in favor of Jewish musicians. "

He has never been a member of the Nazi party and has only rarely obeyed the orders of Nazi cultural policy, behavior tolerated by both Goebbels and Hitler because, if the Master had emigrated, he would have been a martyr "Serious damage to the reputation of Germany land of music." Abroad, however, due to his lack of emigration, he was seen as a sympathizer of the regime, so in some countries, such as the United States, there was a hostile attitude towards him. Not to mention that some suspected that German musicians could be spies.

In 2004, the fiftieth anniversary of his death was celebrated coldly in various countries. In France, the Wilhelm Furtwängler Company, based in Paris, had decided to have a work of youth by the Maestro under the patronage of UNESCO and also in the presence of his wife. The concert was canceled three weeks before the scheduled date.

50 years after his death, therefore, the Maestro still continued to constitute a "case".

Gianlorenzo Capano