What role does the International Criminal Court actually play in the repression of unlawful conduct that may arise during the course of an armed conflict? Is it an absolutely indispensable organ or something that, in practice, can be safely renounced?

To answer these questions, it is first of all necessary to put in place a general premise, concerning the criteria that currently govern that set of rules outlining the correct conduct of international armed conflicts and constituting the ius in beautiful, in order to finally be able to find an answer, as satisfactory as possible, to the questions posed.

The contemporary era is characterized, openly and manifestly, in the juridical sphere by the peculiar tendency to repress, through the elaboration of ever new normative instruments, based on the analysis and classification of social dynamics and human relations, a long series of behaviors provided for and understood by the central legislator as harmful and dangerous for the protection of the subjects belonging to the same system.

The foregoing has been substantiated in the context of the analysis in the elaboration, over the years, of an articulated and complex legislation at international level, aimed, certainly, at guaranteeing the killing of the fighter / adversary during the course of the regular armed conflict started, but always taking into consideration how the single subject present on the battlefield is not actually the opponent / state - with which the conflict that led to the use of armed force was established - but only his "momentary personification", in relation to the event under analysis. Therefore, the defeat of the opposing armed force only as a means for achieving the political objective by virtue of which the instrument of war was used and not as an end. It follows that the provisions in force, aimed at limiting the use of a specific weapon in war, must be understood as aimed at "protecting" the individual fighter from the use of instruments aimed at hitting him directly and, therefore, indirectly the State of membership of the latter, but which does not always involve an adequate achievement of the "political purpose" sought. While, of course, they tend to provoke and configure what today is defined as "superfluous evil" and "unnecessary suffering", in the context of ius in beautiful.

The interest underlying the regulatory intervention in the field of war is therefore substantiated in the need to achieve an effective balance between the purpose pursued by the state / actor, by means of armed force (military necessity), and the protection of the dignity of the single fighter (humanitarian postulate).

In the light of what has been stated up to this point, it is necessary to question and ask how it is possible, given the presence of specific international agreements and treaties aimed at guaranteeing and ensuring the achievement of the aforementioned level of protection, that even today there may still exist situations where the use of an armament or a war strategy otherwise prohibited is concretely not repressed and sanctioned.

Evasion of international principles in plain sight. An example? The case of bullets caliber 5.56x45 mm.

Evasion of international principles in plain sight. An example? The case of bullets caliber 5.56x45 mm.

This caliber, to date, appears to be, together with the 7.62x51 mm caliber, one of the two standards used by NATO and agreed by the member states in order to be able to draw up a list of NATO standard weapons and, more precisely, to use and employ a caliber common for assault rifles and machine guns (LMGs) so that the supply chain can be more economically accessible. It is good to underline, however, that the problem inherent to the caliber under analysis makes absolutely no reference to the intrinsic injury of the shot but to the collateral damage deriving from the aforementioned use and which do not seem to meet the needs of balancing between "military objective" and "law humanitarian "mentioned above.

To understand the above, an analysis of the intrinsic characteristics of the two calibers making up the NATO standard is necessary.

The 5,56x45 mm is smaller and lighter than the 7,62 shot, 5,68 mm in diameter (real) for 44,70 mm in length (57,40 mm considering the entire case) against 7,82 mm in diameter (real) of the second for 51,18 mm in length (69,85 mm considering the entire case) and smaller means cheaper, in relation to the fewer materials needed for its manufacture, faster with a speed average output of 970/990 meters per second against 812 meters per second of the slowest and heaviest 7,62x51 mm and, also, lighter (only 3,6 grams against 9,4 grams of the 7,62x51 mm bullet ), with less weight which in turn implies, in relation to the military strategy (then in use at the time the ammunition came into service), the possibility of carrying a greater number of shots.

But if these are the strategic advantages of a lower caliber, in relation to the effects produced once the target is hit, the damaging effect turns out to be the product not so much of the kinetic energy transported by the bullet, but of that which is transferred to the target. tissues (according to the relationship between the mass of the bullet, its impact velocity and the residual velocity) and this entails, precisely in relation to the lower mass and greater velocity of the 5,56x45 mm bullet, a deformation of the bullet, if it enters in contact with hard surfaces (such as bones) capable of reducing their speed more abruptly, thus resulting in a much higher injury than that resulting from the use of a larger caliber such as 7,62x51 mm. Mind you, speaking of injury in this case we do not intend to refer at all to the mere physical injury, connected with the entry and exit of the bullet from the body (in this case, the comparison in question would not make sense since it is ascertained and undoubted the clearly superior perforation capacity of the 7,62x51 mm caliber) but rather in relation to the side effects caused by the deformation of the same and its stationing in the target's body (characterizing element, as seen, the 5,56x45 mm caliber).

If the objective of using a bullet, according to what is foreseen and established by international law, is only the killing of the opponent, a stationing (statically high in the case study) in the body of the same with consequent deformation and related pain, it certainly leads to the configuration of those figures referred to and defined as "superfluous evil" and "unnecessary suffering", by virtue of which the actual configuration of a war crime is evaluated.

So, in the practical field, is an incorrect attitude always concretely sanctioned? Not always, indeed, in most cases not.

This is because the example set by the International Criminal Court is a paradox, emblem of a void inherent in the competences devolved to it and regarding judging certain behaviors.

In fact, the Court, whose Statute was adopted in Rome in 1988, appears to be a competent body only in relation to the cases and according to the limitations imposed by the aforementioned Statute.. If, in fact, on the one hand this is competent to judge in relation to a large catalog of crimes, specifically reported by art. 5 paragraph 1 of the Statute itself and which also include war crimes, on the other side, according to art. 12, the same body appears to have jurisdiction only in relation to those crimes committed by States, or by members, who have signed the Statute. Not enjoying, however, according to art. 17 paragraph 1 letter. a), of a priority jurisdiction and being able to judge only where the national courts do not intend or are not actually able to carry out the investigation or start the trial or, again, in the event of failure to sign the Statute, in the presence of a specific declaration for means by which the non-signing State accepts the jurisdiction of the Court for itself, for its citizen, or for actions carried out in its own territory, in relation to the crime under analysis. Lastly, art. 124 provides for the possibility for the new signatory state not to submit to the jurisdiction of the Court for a period not exceeding seven years, or less if otherwise provided, from the date of entry into force of the Statute, in the case of war crimes committed on the its territory or by its citizen.

In fact, the Court, whose Statute was adopted in Rome in 1988, appears to be a competent body only in relation to the cases and according to the limitations imposed by the aforementioned Statute.. If, in fact, on the one hand this is competent to judge in relation to a large catalog of crimes, specifically reported by art. 5 paragraph 1 of the Statute itself and which also include war crimes, on the other side, according to art. 12, the same body appears to have jurisdiction only in relation to those crimes committed by States, or by members, who have signed the Statute. Not enjoying, however, according to art. 17 paragraph 1 letter. a), of a priority jurisdiction and being able to judge only where the national courts do not intend or are not actually able to carry out the investigation or start the trial or, again, in the event of failure to sign the Statute, in the presence of a specific declaration for means by which the non-signing State accepts the jurisdiction of the Court for itself, for its citizen, or for actions carried out in its own territory, in relation to the crime under analysis. Lastly, art. 124 provides for the possibility for the new signatory state not to submit to the jurisdiction of the Court for a period not exceeding seven years, or less if otherwise provided, from the date of entry into force of the Statute, in the case of war crimes committed on the its territory or by its citizen.

Therefore, a rather particular picture emerges, where in the absence of signature or the specific declaration referred to in art. 12, a situation of non-punishment emerges as there is no body used, creating something that we could define as a "paradox" understood as the will, yes, to repress, in the abstract, certain behaviors and therefore limit, if not prevent, the committing acts that can be configured as war crimes, but which in objective reality translates into the need, on the part of the guilty, to tacitly accept a judgment that is disadvantageous to him. The question arises spontaneously:

Which culprit, not defeated and aware of what has been done, voluntarily submits to the penalty?

It can therefore be affirmed how this conceived system requires, in order to function correctly and effectively, the need for a not insignificant "moral" element, essential for the existing repression framework to be effective.

But even from this point of view, if it is considered necessary that the one who made a mistake voluntarily submit to the appropriate repressive judgment provided for at international level, does not a paradoxical situation emerge again?

How can one request and expect the existence of such an iron moral sphere in those who, state or physical person, have previously voluntarily committed the aforementioned crimes?

This is how, if on the one hand, the inanity of the International Criminal Court and its jurisdiction to voluntary submission emerges in all its mediocrity, on the other hand, the same Court, although constituted with the aim of crowning a plan to protect human rights, is in reality an empty altar of hopes and dreams that cannot materialize.

If the problems identified are to be overcome, a profound and radical revision of the powers attributed to this international body is necessary, which must be understood almost as a sovereign subject and overlying the States, endowed with powers of investigation and repression not subject to prior consent. . It would be necessary to imagine the birth of an international order perfectly assimilated to an internal national order, with States as citizens and a single central power (obviously elected) subject only to the unavoidable limits of law and not to the economic convenience of the subject States (only on the facade ) to international jurisdiction or self-interest of hypothetical offenders, who, lacking an iron moral conduct, find easy ways to escape international judgment.

This seems, to the writer, the only effective and potential solution that can be shared because, otherwise, the paradoxes will never be resolved, the injustices remedied and the International Criminal Court a real court, but only an extremely expensive representative body. If you really want to implement concrete protection of human rights, ensure compliance with the rules of ius in beautiful, repress improper conduct (whether evident or not) dictated by the feral nature of man, then a total restructuring of the international conception, of interstate relations is necessary, with a consequent reduction in the importance of economic interests. Only in this way can there be Justice, otherwise, embracing the current situation, once again the only definition of "Justice" can only be that interpreted by the winners.

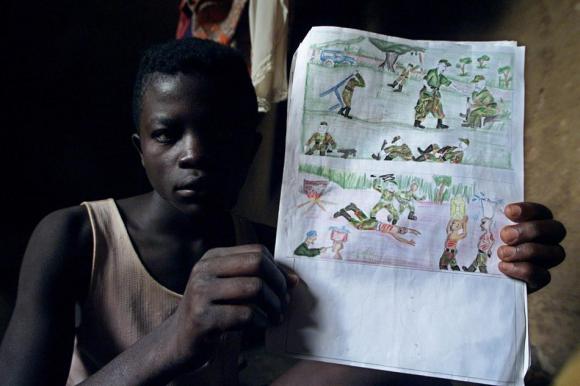

Photo: CPI - ICC / US DoD