"Who said that interest in guerrilla warfare has the characteristics of modernity; the first treatise dealing with the subject is Byzantine and dates back to the 10th century ".

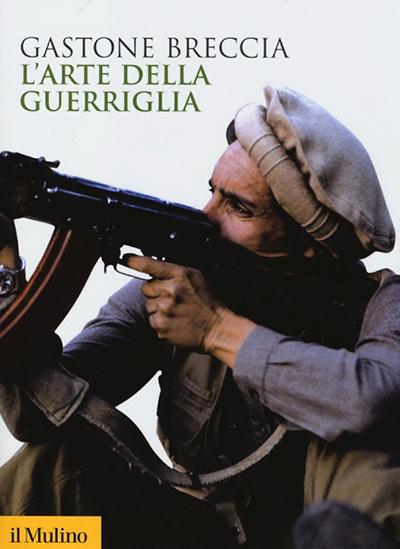

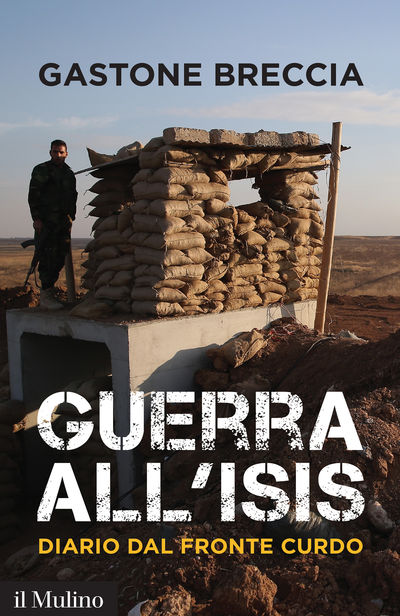

Gastone Breccia, Professor of Byzantine History at the University of Pavia and military historian by passion, goes straight to the presentation yesterday in Bologna of his two last works published for the Mill: "The Art of the Guerrilla" and "War on ISIS "

Two books linked to each other, written to provide scholars and enthusiasts with new tools of understanding with which to interpret current conflicts: strongly asymmetric, non-linear, and unbalanced to the advantage of the weaker contender.

The first volume dedicated to a form of combat, which included among the main mentors figures of the caliber of Sun Tzu, Lawrence of Arabia, Mao Tse Tung, Che Guevara. And the immense Amedeo Guillet.

The text provides a clear definition of the guerrilla theory, the different tactics that distinguish it, with a hint to its legitimacy, because: "We Westerners consider the guerrillas unfair, not remembering that St. Augustine maintained that if we fight for a just cause, it does not matter if we do it in an open field or by resorting to ambushes and tricks".

The author's analysis then shifts to what should be considered a legitimate attack and the dividing line between terrorism and guerrilla warfare; subtle border that identifies in the involvement or not of innocent people.

A scrupulous, lucid analysis, described in a direct and easy to read form, which laid the foundations for the second book, the one dedicated to the war against ISIS.

A job that brought him to the field, to see firsthand how a regular army, the Kurdish one, acts against an irregular one, and interview the military leaders of Iraqi Kurdistan (Peshmerga) and of the Syrian one (PKK).

A journey that allowed him to see closely how the Italian Army paratroopers, in one case the same he had known during a previous study mission in Afghanistan, trained what is (our) first line against Isis: a first line also made up of trenches, as 100 used to do years ago, in which one lives and dies, side by side, in the indifference of a distracted West.

Professor why is it so important to talk about guerrilla warfare in a world like this?

Because the guerrilla is the instrument of many active subjects in the current conflicts, who have no way of adopting regular combat systems: the Afghan insurgents, the Iraqi ones, the insurgents of the Syrian civil war can do nothing but adopt guerrilla tactics because they do not have the tools for a comparison that we would call regular.

Today more than ever this is repeated on a planetary scale: there are many guerrilla outbreaks still on.

This is a comparison that is also reflected on a psychological side, because on the one hand we have Western nations with hyper-protected soldiers, who use weapons and equipment to reduce the risk of losses to zero; on the other hand, combatants as they could have been many centuries ago, with only a personal motivation to fight, and if necessary to die.

This is very true, and poses a very serious moral problem. I felt myself objected to in Afghanistan: you come here and think more about the safety of your men than fighting to win.

Force protection is a very big problem because, for political reasons, Western countries must protect their soldiers, as every dead person weighs heavily on public opinion; and this is perceived as a weakness by our enemies, who are convinced that, against such an enemy, if they hold out, they will certainly win.

And so the guerrilla who exposes himself with turban and Kalashnikov against the super soldier protected by bulletproof vests and hyper-modern armaments acquires, towards his own people, especially in certain cultures still linked to the concept of courage in war and sacrifice, a huge moral advantage.

She is an academic who has written many books on various subjects; however the two volumes he presented today derive from his direct experience on the ground; this aspect of no small importance, which puts it in contrast with the traditional distance that separates the historian from the evolution of the events, which is instead the journalist's natural terrain: why do you prefer to move in the first person?

A little due to the spirit of adventure, partly because I'm excited about being with our soldiers in Afghanistan or the Kurdish guerrillas, to see how they solve day by day certain problems on the ground that we are led to discuss only in the abstract: so a desire to touch, which is not just about the scientific aspect of my research.

A little, and this concerns Kurdistan above all, is the lack of information, of bibliography, of scientific studies on the war against ISIS, which in part forced me to go and collect evidence for myselfquestions, to look for sources on which to gradually build a reflection.

This first book on the war on ISIS is only a first step.

This book brought her to know Daesh at a close distance: what was the impression of the whole phenomenon?

From the military point of view it was probably magnified by themselves, by their propaganda. Militarily he is more vulnerable, with a much more fragile morale than would be expected.

The Kurdish fighters and fighters have repeatedly confirmed to me that the ISIS militiamen, in the face of the first difficulties on the ground, often disband themselves, do not have the tenacity and moral solidity that is commonly attributed to them.

From the military point of view we are therefore led to exaggerate their efficiency.

ISIS is however a complex phenomenon. It is not a single block, but formed by various different elements: the former officers of Saddam's army; guerrilla professionals paid to fight, many of whom come from the Caucasus where they learned and used guerrilla tactics on the ground (against the Soviets or the Russians); and then the idealists, those ready to sacrifice themselves for a very extreme idea of Islam, less efficient on the ground but more lethal when they decide to blow themselves up, turning into a deadly tactical weapon.

Upcoming projects and trips?

A complicated question at the moment because I am under contract with two different publishing houses, for two books that I will have to write quickly: one about the Byzantine wars that I'm finishing and one about Scipione the African. Having finished these two projects, I would like to continue this type of research on the irregular war of the 21st century.

I have an idea to return to Kurdistan where I now have contacts, or to go to Ukraine, in the Dombass, if not in the combat zone, at least in the wider conflict zone, on the side of the pro-Russian rebels.

And this could be very, very interesting.