In recent weeks, it has become increasingly insistent, by some politicians with stars and stripes, and by some press, the voice of a possible opening of the procedure of impeachment towards the new American president, Donald Trump, for the events related to the cd Russiagate.

Let us see, then, what this institute consists of, the conditions under which it can be activated, and the procedural stages that distinguish it.

The origins

THEimpeachment (from "to impeach" = to put in state of accusation) is part of the institutions of the so-called political justice, ie those through which parliamentary assemblies play a function of a jurisdictional type, and constitutes the historical antecedent of modern forms of political responsibility .

Before its insertion into the American constitution, it found its origin in medieval England, following the constitutional crisis of the 1376, in which the Parliament claimed to itself the right to judge the King's Ministers guilty of serious crimes, subtracting this power to the Private Council of the Crown (Curia Regis), reaching the height of its importance in the seventeenth century when, given the principle of the irresponsibility of the monarch («the King can not hurt»), It came to constitute the way to assert the responsibility of the Ministers towards the Parliament, finding formal recognition in theAct of Settlement of 1700.

With the course of time, when a form of political responsibility gradually changed to criminal responsibility, through the vote of confidence (the so-called parliamentary trust), it ended up falling into desuetude (just think, in of the English constitutional history, the last two proceedings of impeachment they are dated 1788 and 1805 respectively).

In the meantime, however, this procedure had aroused interest in the overseas countries, to the point of being even incorporated into the newly formed Constitution of the United States, during the Philadelphia Convention, held between the 25 May and the 17 September 1787 in the Independence Hall of Philadelphia, just for the purpose of reforming the Articles of the Confederation.

In the meantime, however, this procedure had aroused interest in the overseas countries, to the point of being even incorporated into the newly formed Constitution of the United States, during the Philadelphia Convention, held between the 25 May and the 17 September 1787 in the Independence Hall of Philadelphia, just for the purpose of reforming the Articles of the Confederation.

To realize the importance of the introduction of such an institute in the American constitutional system, it was one of its founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin (in the picture on the right), who noticed the fact that, until then, to get rid of the uncomfortable figures, belonging to the executive power, had often resorted to their assassination: precisely because of this, it would have been preferable1, then, to introduce a legalized procedure through which to obtain the same result (the removal from public office of the person involved) without the same brutality.

So, then as today, while Article I, Section 2 and 3, of the American Constitution refers to the relative procedure, with an evident accentuation of the political character of the aforementioned (it is foreseen, in fact, that it - the procedure of impeachment - has no other purpose than to remove the convict from his charge, without prejudice to the possibility of submitting it to criminal proceedings), his article II, Section 4, indicates instead the public offices that can be submitted to it ("the President, Vice President, and all civil servants of the United States") And the related ones reasons ( "conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors ").

The procedure

The indictment of the President of the United States is deliberated by the House of Representatives called to cast its vote on one or more articles of theimpeachment: if an absolute majority is reached even on only one of them, the President is placed in an indictment. After that, it is in the Senate (Senate) that the real process takes place, within which, to some members of the House of Representatives (so-called managers) who act as "prosecutors", that is to say public prosecution, lawyers will be opposed (lawyers) chosen by the President, before a jury composed of the senators themselves, presided over by the President of the Supreme Court2. Any conviction is pronounced with a resolution of the Senate by a two-thirds majority: following it, the President is removed and replaced by the vice-president, who assumes his full functions. The verdict is final3.

The rules

Beyond what has been said so far, the peculiarity of the procedure of impeachment it is the absence of pre-established procedural rules, unlike ordinary judicial proceedings, as evidenced by the, albeit meager, precedents in the matter.

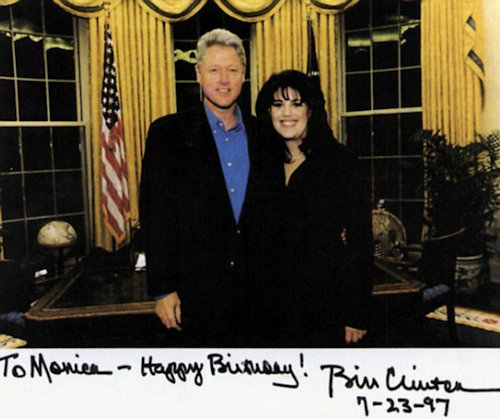

For example, in what was former US President Bill Clinton in the 19994, for the scandal tied to the intern Monica Lewinsky, they were granted four days to the accusation to collect the guilty trials, and the same number to the defense for their refutation. It was for this reason that the Senate, on its own, decided to listen to its witnesses both in person and through videotape. In this regard, Bob Barr, a former Republican member of the prosecution on that occasion, had to criticize such circumstances that, in addition to the imposed quota both regarding the number of the escutable witnesses and the length of their depositions, they ended up, according to him, by making the condemnation of the democratic president virtually impossible. Moreover, according to the same Republican representative, it was unacceptable the absence of predefined rules that, as a consequence, ended up increasing the discretion of the jury (the Senate, as mentioned) in the appreciation of some proofs rather than others, with evident risk of manipulation of the final result, not anchored to objective evidence but to interpretations (more political than juridical) of the moment ("Impeachment is a creature unto itself; the jury in a criminal case does not set the rules for a case and can not decide what evidence they want to see and what they will not").

For example, in what was former US President Bill Clinton in the 19994, for the scandal tied to the intern Monica Lewinsky, they were granted four days to the accusation to collect the guilty trials, and the same number to the defense for their refutation. It was for this reason that the Senate, on its own, decided to listen to its witnesses both in person and through videotape. In this regard, Bob Barr, a former Republican member of the prosecution on that occasion, had to criticize such circumstances that, in addition to the imposed quota both regarding the number of the escutable witnesses and the length of their depositions, they ended up, according to him, by making the condemnation of the democratic president virtually impossible. Moreover, according to the same Republican representative, it was unacceptable the absence of predefined rules that, as a consequence, ended up increasing the discretion of the jury (the Senate, as mentioned) in the appreciation of some proofs rather than others, with evident risk of manipulation of the final result, not anchored to objective evidence but to interpretations (more political than juridical) of the moment ("Impeachment is a creature unto itself; the jury in a criminal case does not set the rules for a case and can not decide what evidence they want to see and what they will not").

What is meant by "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors".

Betrayal, corruption or other crimes and misdeeds: these are the cases in which the President of the United States, or the other positions envisaged, may be subjected to impeachment.

As there are no precise procedural rules in the important phase that takes place before the Senate, even these concepts there is a precise definition (nor, perhaps, could be), ending with being evaluated and considered, from time to time , through an interpretation (if you want to define it) and a political, as well as legal, contextualization.

Still referring to the Clinton case, Robert Byrd, a Democratic senator of the time, from West Virginia, had to say to his colleagues that, while considering the president evidently guilty of perjury, removing him from his post, at that time, would have been a bad idea; as a result, though reluctantly, he voted against it ("Therefore, I will reluctantly vote to acquit").

If we consider that, then, Clinton was submitted to impeachment from a Republican-majority Congress, still managing to be acquitted (since it was believed that what happened, belonged more to his private sphere than to public), we can well understand how, in the case of Trump, think of a procedure of impeachment, be even more difficult (let alone a conviction), given the overwhelming majority of his party in both branches of Congress (although, as you remember, there were heavy splits, on his candidacy, during the pre-election period).

If we consider that, then, Clinton was submitted to impeachment from a Republican-majority Congress, still managing to be acquitted (since it was believed that what happened, belonged more to his private sphere than to public), we can well understand how, in the case of Trump, think of a procedure of impeachment, be even more difficult (let alone a conviction), given the overwhelming majority of his party in both branches of Congress (although, as you remember, there were heavy splits, on his candidacy, during the pre-election period).

The twenty-fifth amendment

Almost wanting at all costs to chase the dream of dismissing the forty-fifth American president, democratically elected, some press organs and certain political commentators, in a far from neutral, were quick to hypothesize, as an alternative toimpeachment, the recourse to the instrument foreseen by the twenty-fifth amendment (section 4) of the same US Constitution (introduced in 1967), according to which the vice president and the majority of the cabinet of government can send a letter to the Congress, claiming that the president is incapable of acquitting to his homework. Following this, the powers would then pass to the deputy, but if the president replied with another written message, he would immediately resume his duties. At that point the number two of the White House could insist and then the House of Representatives and Senate would be called to decide, with the quorum of two thirds, who to entrust the country.

But this institute refers to a supervening incapacity to understand and to want of the number one of the White House, or of its physical impossibility, certainly not to his (more or less criticizable) political conduct of the Country: situation, therefore, that does not seem not even conceivable, in this case, with some peace of mind.

It is no coincidence, in fact, that in the fifty years since its entry into force, this institute has found application in very few cases: only twice as regards the replacement of vice-presidents (i.e., when Gerald Ford took over from Spiro Agnew, in 1973, and when Nelson Rockefeller did the same against Ford in 1974) and six times for that of presidents (but, on all occasions, it was invoked by the same - presidents - and on a purely temporary basis, in concomitance with health checks and / or hospital admissions of the moment. In no case, however, when the current president was not "compos mentis suae": and this, not even when, even when Ronald Reagan was hospitalized following the attack suffered in 1982).

In short: without entering into the political action taken up to now by the new tenant of the White House, it is highly probable that its protesters, both national and international, will have to wait for the new (and distant) elections to change an election result that, altered in other ways, it would risk being forcibly subverted, in contempt of the long democratic tradition of the United States.

So then you could, in some ways, start talking about one Usagate.

1 Josh Chafetz (2010). "Impeachment and Assassination". Minnesota Law Review.

2 If it were, instead, a judgment against the other offices, the same function would be carried out by the Vice-president of the Supreme Court.

3 In case Nixon v. United States (1993), the Supreme Court, in fact, established that the verdict issued as a result of federal judgment, such as that concerning the President of the United States, or high public office (including judges) was unquestionable, unlike ordinary trials. In reality, theimpeachment it is also foreseen at the state level, and it can be subjected to local public officials, including the governors themselves.

4 The other illustrious precedent was that of the Republican President Andrew Johnson in the 1868; Richard Nixon, however, resigned in the 1974, when the process had just begun in Congress, following the so-called Watergate.

(photo: US DoD / web / US Coast Guard)