Ukraine is today at the center of a world question capable of determining the rupture of one status which has lasted since the end of the "Cold War". A land historically different from Russia which, in the modern age, has matured a varied cultural root having undergone the influences of other cultures: part of it was from the Hapsburg Empire, while the easternmost part was affected by the influence of the Tsarist empire.

Among the most important historical episodes in Ukrainian history, there was the battle of Poltava, when in 1709 the Russians of Peter the Great (following image) defeated the Swedish army of Charles XII. Without doubt two great leaders, but between the two it was Peter the Great who went down in history thanks to his civil and military reforms that returned Russia to a central role in the European political games of the eighteenth century1.

At that time Ukraine was considered the land of the Cossacks and already in the seventeenth century the French ambassador to Constantinople de Cessy reported in Paris of the continuous incursions of Ukrainian Cossacks both towards the capital and towards the Black Sea. a suspicious attitude towards St. Petersburg and when the King of Sweden Charles XII attacked Peter the Great, the Ukrainian Cossack Ivan Mazeppa openly sided with the Swedes. After the battle of Poltava and the serious Swedish defeat, Tsar Peter demanded from the Swedes the return of the emigrant Cossacks who had fought for Charles XII and it was only the intercession of France that prevented their massacre.

THEqueen (or ataman, the highest military rank among the Cossacks) Pylyp Stepanovych Orlik (successor of Mazeppa) took charge of defending the rights of Ukraine in Europe with the clear support of France. It was also Orlik who became head of the Ukrainian contingent that allowed the French to win the battle of Bergen in 1759. A story of rebellion, therefore, which in 1789 was influenced by what was happening in Paris.

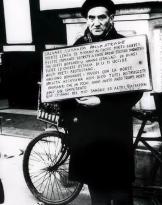

The tree of freedom in Kiev

The tree of freedom in Kiev

Shortly after the revolution, citizen Parandier, French representative in Hamburg and attentive to matters with Russia, sent a dispatch to the Public Health Committee in Paris explaining why Ukraine was the decisive factor that allowed the Russians to wage war. : "Ukraine supplies them with all the necessary grain, the inhabitants of Ukraine are intrepid, courageous, skilful, disinterested and jealous of their independence"2.

Following the doctrine that the revolution was a principle exportable to any country ready to welcome it, the Committee of Public Health issued a proclamation that France would support by all means the uprising of the Ukrainian Cossacks: "warlike nation, moreover free, subjugated by Peter I and in which it will be important to revive the feeling of freedom to free oneself from the yoke, we want to see the tree of freedom in Kiev"3.

After the revolutionary whirlwind, Napoleon, emperor of the French, inherited the policy that belonged to Louis XIV and then to the Committee; with regard to Ukraine, he received all the help from Minister Talleyrand who, by pure coincidence, met Petro Mohyla, a fervent Ukrainian patriot and Metropolitan of Kiev, while attending the college of La Flèche.

Between 1806 and 1807 the question of Ukraine was at the center of a broader debate concerning Eastern Europe and in particular the possible birth of an independent Polish state. In a report by Baron Jean François de Bourgoing, plenipotentiary minister in Saxony, it became clear that Alexander I's Russia had bad relations with some neighboring states, mainly because his imperialist policy was assimilating them in an arbitrary way: the invasion of Crimea and of the Cossack nation, the partial subjugation of Moldova and that of a part of Poland during the partitions of the eighteenth century.

In 1807, Napoleon inflicted the first severe defeat on the Russian Empire, beating Alexander's troops at Eylau and Friedland and then arriving at the fateful peace of Tilsit in July of the same year. The emperor sanctioned his dominance in Europe, imposing his conditions on Frederick William, King of Prussia and on Tsar Alexander I. At that point Ukraine became a central topic on the French political agenda also because the Tilsit treaty looked more like a truce than a lasting peace; Napoleon knew that sooner or later the balance between the two powers would be broken and a war would be inevitable. It was therefore important to understand who - in the event of a clash - could have lined up with the emperor.

Ukraine - according to the memo drawn up by Leclerc, a foreign affairs employee - would have been the only eastern region to be able to give significant support to the Russian army since the grain reserves in the other regions were negligible. In his report Mémoire sur le causes de l'ambition de la Russie et les moyens de la réprimer the French diplomat imagined a new geography with a great Poland whose borders would reach from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. Only in this way, and together with the union of Ukraine and the Cossack countries, would Russian expansionism find a valid and "Napoleon would have rejected the Russians in the depths of their deserts"4.

Napoleonides and the Russian campaign

Napoleonides and the Russian campaign

What Napoleon prophesied on the Tilsit raft became a harsh reality in 1812.

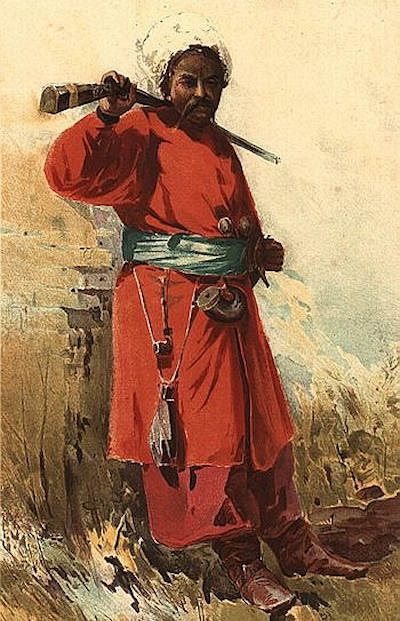

Alexandre Maurice Blanc de Lanautte count of Hautervie, minister of foreign affairs and bitter rival of Talleyrand, wrote a text dedicated to Ukraine in which he inserted the history of the campaigns of Charles XII (image), quoted the works of Voltaire, de Bellervie, but above all he reported a passage from the correspondence of de Bonnac who in 1708 was French delegate to the court of the king of Sweden: "Charles XII immediately entered Ukraine and if this nation did not take sides with him I do not see how the war could continue; Ukraine rich and abundant in livestock and food has inhabitants who carry almost all kinds of weapons, they will be able to serve him as warehouses and let him pass the food for his army in the heart of Muscovy since it was burnt and desolate "5.

The annotations of the Count of Hautervie were a warning to the emperor: to get to Moscow it was important to safeguard the supply lines and this would only be possible with the friendship of Ukraine.

On November 16, 1811, the Duke of Cadore, Jean-Baptiste de Champagny approached Baron Bignon, a diplomat residing in Warsaw, to send prompt information to Paris on Podolia, Volhynia and Ukraine with a precise description of the roads and in particular on the Lemberg-Kiev and Dubno-Kiev line along the Dnieper River.

Bignon's information is proof that in 1812 Napoleon intended to pass through the Ukraine, retracing the path of Charles XII.6.

When the war against Russia appeared inevitable, on 11 December 1811 Napoleon sent a letter to the Duke of Bassano Bernard-Hugues Maret, asking that Bignon be in charge of organizing some sort of secret police to gather information on Lithuania, Volhynia, Podolia and Ukraine. . Officers affiliated with this police body had to inform Paris about the state of the fortifications and of the roads from St. Petersburg to Vilna, from St. Petersburg to Riga, from Riga to Memel and on the communication routes of Kiev.7. In fact, the zealous Bignon had been spying on what was happening in Kiev for some months now.

On 11 April 1811, the field agent Lubienski sent a first report to Bignon, reporting that there was a strong discontent with the Russians among the people: some public buildings had even been set on fire and many were hoping for a "war of liberation ”Led by the French8.

In 1812, the Comte d'Hauterive compiled theExamen des frontières de la Pologne considered uniquely sous le rapport militaire where he imagined the creation of an independent state that the emperor would invest as such. A state that would include the Duchy of Czernihow and Poltava, stretching along the Dnieper to Orel: "The Cossacks, known by the name of Zaporogi or Zaporoviani (beyond the Cataracts) thus reunited with the Crimean Tatars, they will be able to form a single state under the name of Tauride [so the ancient Greeks called the Crimea nda]". The suggestion was even to name this new land Napoleonide, but it was later abandoned.

In 1812, the Comte d'Hauterive compiled theExamen des frontières de la Pologne considered uniquely sous le rapport militaire where he imagined the creation of an independent state that the emperor would invest as such. A state that would include the Duchy of Czernihow and Poltava, stretching along the Dnieper to Orel: "The Cossacks, known by the name of Zaporogi or Zaporoviani (beyond the Cataracts) thus reunited with the Crimean Tatars, they will be able to form a single state under the name of Tauride [so the ancient Greeks called the Crimea nda]". The suggestion was even to name this new land Napoleonide, but it was later abandoned.

The territorial hypothesis developed by the French diplomat also included some particularities regarding the population and the most suitable form of government: "This state, composed for the most part by a population always on horseback, will be governed by a leader and by means of a constitution suited to their way of being, with the prospect of political independence they will soon form a civilized nation that will constitute one of the more resistant barriers to Russia's ambitions and its claims on the Black Sea and the Bosphorus "9.

After political analysis, d'Hautervie entered the military, expressing all his admiration for the Cossacks described as strong, robust, courageous, indefatigable and highly intelligent10. Obviously a military force like that of the Cossacks Zaporozihan (Ukrainian Cossacks), but well determined, would have been useful to the French: "We will get more than 60.000 men for the light cavalry, of which 10.000 will be employed in the French cavalry where they will be very useful for reconnaissance or to surround and pursue the enemy, and to guard the most distant roads. Ukraine will be useful for the supply of their horses and will be able to give from 40 to 50.000 horses per month "11.

The most important question concerned the eventual recognition of this new state by the Emperor Napoleon who - still far from conferring independence on Poland - would certainly have hesitated even with respect to Ukraine.

Charles Louis Lesur, writer and former member of the Public Health Committee, confirmed that he was a skilled historian when Napoleon confided to him a study of the Cossacks. The first edition of his volume Historie des Cosaques it was published in 1813 and very few copies exist: in these pages you can read very interesting passages about Ukraine and the character of its inhabitants: "Ukrainians are more generous, more sincere, more polite, more hospitable and more hard-working than Russians; they offer living proof of the superiority that civil liberty gives to men who are not born into servitude"12. In addition, Lesur described the terrible repression suffered by the Ukrainian Cossacks after Mazeppa allied himself with Charles XII: "Wherever the Russian generals found the Cossacks, they had orders to put them to the sword […]. The Tsar's plan was to subdue absolutely all of Ukraine. The inflexible Tsar was thirsty for the blood of all nations"13.

Charles Louis Lesur, writer and former member of the Public Health Committee, confirmed that he was a skilled historian when Napoleon confided to him a study of the Cossacks. The first edition of his volume Historie des Cosaques it was published in 1813 and very few copies exist: in these pages you can read very interesting passages about Ukraine and the character of its inhabitants: "Ukrainians are more generous, more sincere, more polite, more hospitable and more hard-working than Russians; they offer living proof of the superiority that civil liberty gives to men who are not born into servitude"12. In addition, Lesur described the terrible repression suffered by the Ukrainian Cossacks after Mazeppa allied himself with Charles XII: "Wherever the Russian generals found the Cossacks, they had orders to put them to the sword […]. The Tsar's plan was to subdue absolutely all of Ukraine. The inflexible Tsar was thirsty for the blood of all nations"13.

When Napoleon, in June 1812, crossed the Niemen with his troops he did not follow the same plan as Charles XII and Ukraine remained outside the French strategic plan. Russian officials residing in Ukraine nevertheless received instructions to monitor the population as independence pushes pushed towards an alliance with the French. This did not happen, however the Ukrainians decided to put up a passive resistance, hindering the recruitment of men for the Russians who from the 4 planned for every 100 inhabitants went to 1.

Despite the nationalist ferment against the arrogance of Alexander I, despite the initial successes of Napoleon, part of the Ukrainians served the Russians with some Cossack regiments. The governor of Eastern Ukraine, Yakov Lobanov-Rostovsky managed, in fact, to bring together four regiments with the promise that these - at the end of the war - would remain active as part of the Cossack nation.

History changed when Napoleon's Grand Army was forced to retreat: the emperor attempted to pass through Belarus, thus trying to reach eastern Ukraine. On that occasion, the borders were defended by Ukrainian regiments who, frightened by Napoleon's policy of being too favorable to Poland, were afraid of coming under the influence of Warsaw. It was therefore more convenient to remain in the shadow of St. Petersburg.

The Cossack cavalry

Among the various specialties that made up the cavalry corps at the disposal of Alexander I, there were some irregular units made up of Cossacks, Kalmyks, Tatars and Bashkirs. Of all these, the Cossacks had a terrible reputation as falling into their hands meant certain and violent death. Their real effectiveness on the battlefield was always the subject of discussion: although they were fast and deadly in the attacks in no particular order against small retreating groups, faced with a well-organized formation, or even worse in front of an infantry square, they did not know how to behave and often had the worst of it.

The Cossacks were fighting groups composed of 500 to 1000 men and all had a close link with the territory where they operated. Within departments or otherwise known as Pulk there was a hierarchy that saw an absolute leader Ataman who headed 5 to 10 named squadrons Sothnia. Usually they rode small and very fast horses and were armed with spears and curved sabers.

Over the years the Cossack formations received an increasingly complex organization, similar to that of the regular Russian regiments, even including artillery units complete with 20 3-pound guns, therefore very light and easily transportable.

The Don Cossacks enjoyed an excellent reputation as fighters, but even better were the Black Sea Cossacks so much so that an old adage went "A Black Sea Cossack is worth three Don Cossacks"14.

Some units were considered rebellious in the sense that they rejected the authority of Russia such as the Black Sea Cossacks themselves and the Zaporozihan (or zaporogi) Ukrainians.

1 Before the battle of Poltava, Peter the Great initiated a series of reforms aimed at modernizing the structure of the Russian army for several centuries. He replaced the old ones streltsy (regiments) who had wanted his father with new style regiments. To this he added the creation of an artillery and engineering school less and less dependent on the hiring of foreign officers. He introduced the linear tactics he had learned from the Swedes and developed the metallurgical and textile industries to make the military departments more and more equipped and independent. After the battle of Poltava in 1709, the first training manual published in 1716 also appeared, with the consequent foundation of a military college to unify the command unit. Among the most significant objectives set by Peter was the reform and strengthening of the Russian navy which at his death included 50 warships and 700 smaller ships. DL Smith, "Peter the Great" in FD Margiotta (edited by) Brassey's Encyclopedia of Military History and Biography, Washington-London, Brassey's, 1994, p. 780.

2 Elie Bortchak, "Napoléon et Ukraine" in Revue des Etudes Napoléoniennes, Tome XIX, July-December 1922, p. 27.

3 Ibid.

4 Ivi, p. 29.

5 Ivi, p. 30.

6 In Napoleon's opinion, Charles XII had done nothing wrong in his march to the heart of Russia, yet he had arrived in Ukraine too late. In fact, he should have arrived when Ivan Mazeppa, a Cossack rebel, had asked for help, fearing a Ukrainian-Swedish alliance.

7 Napoleon Ier, Correspondance de Napoléon Ier publiée par ordre de l'empereur Napoléon III, Paris, Imprimerie Impériale, 1867, Volume 23, p. 111.

8 Bortchak, cit., P. 32.

9 Ivi, p. 33.

10 In 1811 the Cossack units assigned to the borders of Russia were as follows: in Finland 3 regiments, along the border between Poland and Dniester 13 regiments, with the army of Moldova 29 regiments, on the Don 12 regiments, in Georgia 8 regiments, in Orenbourg (eastern Russia) 4 regiments and a Calmucco regiment, in the Caucasus 6 regiments called “colonial” and 3 called Voisko. In the summer of 1812 from Ukraine (Kiev and Kamieniec Podolski) were established 4 regiments of Ukrainian Cossacks each with 8 squadrons.

https://www.napolun.com/mirror/napoleonistyka.atspace.com/cossacks.htm

11 Bortchak, cit., P. 32.

12 Ivi, p. 36.

13 Ibidem, p. 37.

14 C. McNab, The armies of the Napoleonic wars, Gorizia, LEG, 2012, p. 309.