Before its dissolution in 1991, the Soviet Union was a key player in sub-Saharan Africa. But in the aftermath of the Cold War, the Russian Federation practically withdrew from the continent. Only between 2006 and 2009 did this trend begin to reverse: first Vladimir Putin, and later Dmitry Medvedev, I visited the African continent, paving the way for the so-called "return to Africa" of the Russian Federation.

An important step in this direction was the Russia-Africa summit held in Sochi last year. Yet in an international context with regard to African markets, resources and human capital, Russia still has limited options. His ambitions in Africa are hampered by his late arrival, by relatively scarce economic resources, by the lack of attractiveness of his "economic model" and by a certain ineffectiveness of his "soft power". Therefore, to date, Russia is still not able to compete in a conventional sense with the main players in the region. This prompted Moscow to act unconventionally. In the Russian context, this implied forcing some rules through the use of contractors / mercenaries. Hence the rise of Russian private military companies (PMC) in sub-Saharan Africa, a region endowed with natural resources but characterized by strong instability and the perpetual threat of terrorism.

"How steel was tempered": Russian (para) military presence in Africa

To gain ground in Africa, during the Cold War, the USSR relied on technical-military cooperation (vojenno-tekhnicheskoye sotrudnichestvo). This included sending Soviet military personnel (more than anything else) "Advisors"). Usually, these advisers did not take part in combat actions. Their main goal was to offer training and consultancy services. A crucial step came in the second half of the 80s with the so-called "border wars", a series of small conflicts waged by the Libyan leader Muamar Gaddafi against neighboring states. The Soviet army fought on Gaddafi's side, through the use of mercenaries1. After 1991, many of them remained in the country. And in fact they became the first Russian private military contractors on the continent.

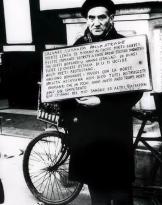

Between the 90s and the late 2000s, the activities of Russian contractors in Africa became tactical and uncoordinated with consequent difficulties in competing with similar Western private military companies (Western Private Military Security Companies, PMSC). Similarly to what happened with some Western antagonistic peers, in some cases, the activities of the contractors Russians have been difficult to separate from ordinary criminal activities. As, for example, happened in 2012, during the notorious "story of the Myre Sea Diver"2, an episode in which a ship belonging to a Russian security company, the Moran PMC - reportedly connected with the notorious Wagner Group3 - was seized by the Nigerian authorities on charges of arms trafficking. Otherwise, private security companies (PSC), such as the PMC of the RSB group4, they have carried out legitimate missions non-combat.

After 2014 something changed. Consolidation of Russian activities in Africa came through Yevgeny Prigozhin5, a billionaire with some criminal background. At least on the surface, Prighozhin has taken a leading role in matters relating to private military companies.

Russian mercenaries in Africa: operations and complications

The activity of Russian PMCs in sub-Saharan African countries is based on a model based on three different schemes. First, if there are natural resources at stake. Second, if there is economic backwardness and political instability. Third, if there is a threat of extremism or terrorism and (on many occasions) of international isolation. Therefore, Russia's operating principle follows the formula developed in Syria: "protection in exchange for concessions" - lucrative agreements with local industries in exchange for (para) military services.

The first proven step by Russian private security companies on the continent was the Central African Republic (CAR), a country torn by the intense civil war since 2012. Unable to defeat the rebels, President Faustin-Archange Touadéra asked for help in Moscow6also seeking support to ease the international arms embargo. Russia answered the call: in 2018 a first group of military advisors arrived in the country together with a load of weapons. They were deployed with a mandate7 UN (Res.n. 1207). Unofficially, however, they were joined by some Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group8. The mercenaries were reportedly expected to protect Lobaye Invest Ltd's Prigozhin property9. It is also worth mentioning that a Russian citizen even became President Touadera's national security adviser (Valery Zakharov, former intelligence officer, who worked for Prigozhin).

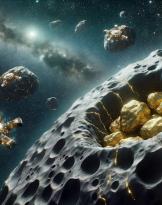

Although it could easily be concluded that these developments appear to be an indisputable victory for Russia in the Central African Republic, the reality is, in truth, a little more convoluted. From a geo-economic point of view, the true extent of local mineral resources (gold and diamonds) may have been far exaggerated10. So for Russia (not for individual "businessmen" like Prigozhin), engaging massively in the country will not bring major economic benefits. If Russia's final goal in the Central African Republic was geopolitical, which would include the overthrow of French hegemony and the creation of a HUB (logistical foothold) to cover other more profitable areas, such as Angola, Russia's move it lacks common sense11,12.

In the short and medium term, the French are difficult to replace having a consolidated presence for years, and being the main aid provider to the country in question. Should this change, Russia will be unlikely to be able or willing to take up that legacy and invest accordingly in the Central African Republic. This would also undermine the credibility of Touadéra, sympathetic to Russia. Likewise, it is unclear how Russia's efforts in the Central African Republic can parallel accelerate progress in Angola. Aside from cultural, linguistic and political differences, these two countries have different bargaining power. Perhaps the ambiguous nature of any "victory" has made Russia's military-political leadership cautious about too many promises. It is for these reasons that the best Russian high-ranking officers had shown themselves to be wary of an idea expressed by the Defense Minister of the Central African Republic, Marie-Noëlle Koyara, about the construction of a Russian military base in CAR13.

The second stage of Russian private military companies was Sudan, a country ostracized by the international community for hosting terrorists and conducting explicit atrocities against its population. Russian involvement was based on the agreement14 signed between al-Bashir and Medvedev in 2018, in which the M-Invest group connected to Prigozhin obtained a concession on the extraction of gold. Despite the similarities, Russia's actions left no trace of legitimacy: the Russian mercenaries arrived15 and began to operate16 in the country with the consent of the local dictator Omar al-Bashir. After visiting Russia several months earlier, al-Bashir had also invited Russia to build a naval-military base in his country. International sources have accused Russian mercenaries of a violent crackdown on local popular protests. Russian officials first shrugged, but later admitted the presence of "specialists" in the area, stating that the only mission of these specialists was only training and advice.

The second stage of Russian private military companies was Sudan, a country ostracized by the international community for hosting terrorists and conducting explicit atrocities against its population. Russian involvement was based on the agreement14 signed between al-Bashir and Medvedev in 2018, in which the M-Invest group connected to Prigozhin obtained a concession on the extraction of gold. Despite the similarities, Russia's actions left no trace of legitimacy: the Russian mercenaries arrived15 and began to operate16 in the country with the consent of the local dictator Omar al-Bashir. After visiting Russia several months earlier, al-Bashir had also invited Russia to build a naval-military base in his country. International sources have accused Russian mercenaries of a violent crackdown on local popular protests. Russian officials first shrugged, but later admitted the presence of "specialists" in the area, stating that the only mission of these specialists was only training and advice.

The image of Russia's success in Sudan has flaws. After the fall of al-Bashir in 2019, the new interim government has sought to diversify its foreign policy, appealing to the United Arab Emirates and Turkey and seeking to strengthen ties with the United States, after over two decades of silence . The China17, with enormous control over the local oil sector, remains one of the most powerful players in the country. As for Russia - which hastened to recognize regime change in Sudan - the bad aftertaste remains in the mouth for its involvement with the old regime, despite the talks18 between Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov (a key figure in African diplomacy in Moscow) and the provisional Sudanese authorities after the overthrow of al-Bashir.

A third country where Russian private military companies operate is Mozambique, a country endowed with natural resources but devastated by Islamic radicalism. Local authorities have never hidden the hopes that Russian experience in counter-terrorism or insurgency operations could help local armed forces resolve the problem. Those expectations19, however, they have so far proved too ambitious. As predicted by analysts specializing in PMCs in Africa, Russian contractors have also struggled to try to contain the problem. Commitments to the insurgents resulted in big losses20. These defeats are said to be combined with the inability to find a common language21 with the local military, have changed the mood22 local political-military leadership. The results questioned the ability of Russian mercenaries to solve the problem in Cabo Delgado.

Intermediate results

The use of PMCs in sub-Saharan Africa has so far not produced great benefits for Russia. Furthermore, the situation is unlikely to change in the short term. The problems faced by local governments - youth radicalization, terrorism and Islamic fundamentalism - need global reforms. Here, Russian mercenaries on the ground could even have negative effects. In the face of rebel forces and growing tensions with local armed forces, the presence of Russian mercenaries could trigger intra-African tensions. For example, the advent of Russian contractors in Mozambique has caused negative feelings in South Africa, Russia's main regional partner. And any setback - like the one in Mozambique - will probably bring discredit to the global perception, effectively cutting off any future African customers.