When in the German trenches we heard at a distance that cry of warning that broke the throat to scream 'Pfeile' (arrows), the terror spread in an instant. Not a noise, not a whistle, just the sound of an English or French biplane flying over the enemy positions and shortly thereafter would pull yet another 'cord' to operate a lethal simplicity system and cover the trench of little ones' darts' able to pierce, thanks to the law of acceleration of the fall of the grave, a helmet with the entire skull in his wake.

Notes like flechette (from the French, "little arrows") this kind of 'darts' was the sneaky protagonist of the first and rudimentary 'bombing' carried out by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Aéronautique Militaire in the initial phase of the First World War.

Although the first bombing with explosive devices had already been successfully carried out in 1911 by the Italian Giulio Gallotti in the Italian-Turkish War - "(...) and you Gavotti, from your slight slope bent in the danger of the winds on the enemy who ignore the new assault! " (Gabriele D'Annunzio, Canzone della Diana) - at the dawn of the First World War, aerial bombardment was still a completely experimental phase. If towards the end of the conflict a twin-engine bomber Handley Page was able to unhook an unthinkable aeronautical bomb from 1,650 libre (750 kg), it all began with small and rudimentary darts that measured just over 5 inches (12 cm).

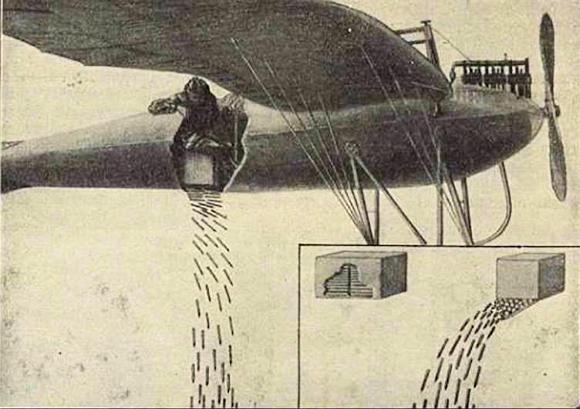

The fléchettes were crammed into a box arranged inside the fuselage; this generally contained a batch of 500 darts and was connected to an 'opening and unhooking' system operated by a cord. Their effect was devastating because of the speed that the little metal dart bought during the free fall. According to a report by a German military doctor, the dart was able to punch a helmet by killing a soldier from the wound on his skull. If the dart instead had fallen on the torso or on the shoulder, it was able to cross the scapula, the lungs and reach other vital organs without leaving the victim any escape. For this reason, from the testimony of a German soldier it was learned that if you were under fletcher throwing it was more desirable to lie down on the ground, increasing the probability of being hit but exposing (we hoped) to easily identifiable and non-lethal injuries.

The fléchettes were crammed into a box arranged inside the fuselage; this generally contained a batch of 500 darts and was connected to an 'opening and unhooking' system operated by a cord. Their effect was devastating because of the speed that the little metal dart bought during the free fall. According to a report by a German military doctor, the dart was able to punch a helmet by killing a soldier from the wound on his skull. If the dart instead had fallen on the torso or on the shoulder, it was able to cross the scapula, the lungs and reach other vital organs without leaving the victim any escape. For this reason, from the testimony of a German soldier it was learned that if you were under fletcher throwing it was more desirable to lie down on the ground, increasing the probability of being hit but exposing (we hoped) to easily identifiable and non-lethal injuries.

According to the British magazine The War Illustrated, the British pilots were not at all happy to lend themselves to this practice of bombing considered a decidedly 'dirty' work, but the gradual increase in tension between the factions, also caused by the bombardments retaliation wanted by Kaiser and the conduct often called 'ungentlemanly' to avert himself, he ended up making him go with a 'way' like another to make war. Although deadly, especially when dropped on an infantry charge, the accuracy of this weapon left something to be desired and proved extremely limited. In fact, it did not possess the destructive characteristics of the aeronautical bombs that soon outperformed it.

On the battlefields they were mainly used between the 1914 and the 1915; the discovery of German installations completely riddled with sharp blows suggests that it was widely used during the Battle of Mons. Another confirmed use of the flechette the 27 March 1915 took place on the Metz railway junction, revealing the enormous limits among other things.

Who would have been able to think that the development of aeronautical technology and armaments would have allowed, just 30 years after the launch of small medieval 'darts', to drop a single bomb capable of devastating an entire city?