French President Macron launched the idea for the creation of a European army. An old idea because, as noted by the Russian premier Putin, it was already a thought of Chirac and then Mitterrand who, along with Chancellor Khol was one of the proponents of the Eurocorps 1992. The American leader Donald Trump has judged Macron's proposal immoral, without knowing that the desire to unite the European armies under a single flag has a historical value that goes far beyond the purposes of Chirac. As is well known, the Americans often fight with European history unless it touches their interest in some way. If only the boys of Washington took the trouble to leaf through a text of military history they would realize how Europeans have already experienced the idea of a unitary army, grouped by a single ideal although imposed militarily.

From mercenaries to the national army

If we analyze some order of battle of the armies of the Ancient Regime we realize how these were a mix of mercenary units made up of soldiers coming from all over Europe. This migratory phenomenon of the "weapons traders" did not concern only the lower ranks whose path can be well represented by the film Barry Lyndon of the great Stanley Kubrik, but even the officers who - all noble by birth - included military service abroad as an important stage in their formation. For example, if we take the French army of Francis I in the 1522 we note that it was composed for 71% by German, Swiss and Italian mercenary troops and only a small part of national elements. Over the years the use of mercenary units at the service of the king of France came to an abrupt end, nevertheless in the army of Louis XIV Italian, Swiss, Irish and even Scottish regiments remained in service. Likewise, the Savoy armies of Vittorio Amedeo II also benefited largely from paid soldiers: at the end of the 1694 - explains the British historian Chistopher Storrs - the king had to recruit two German and three Irish companies to complete the second battalion of the Chiablese regiment. This practice involved almost all the European monarchies of the Old Regime until, in the revolutionary France of 1789, the idea of composing a national army took shape, founded on the principle that every citizen had to serve in arms for the homeland.

The introduction of the Jourdan-Delbrel law of the 1798 actually marked a break with the past, although several armies that faced France remained set according to a traditional model. The revolutionary armies were therefore moved by a nationalist feeling whose vocation was to free the other peoples from the ignorance and iniquity of the laws imposed by the aristocracy. On paper the principles of the 1789 held up well, also because the approach of the troops to the song of the Marseillaise raised the spirit of many peoples eager to demolish, once and for all, the ancient state facilities of the Old Regime. In the new ideas there was no longer any obligation of fidelity to a king appointed by an imaginary divine will, no recruitment contract for soldiers or social differences: there was rather a state governed by fair laws and guarded by a national army that collected as reward the daily pay. Although the founding principles were really loaded with good intentions, the reality was very different because the irruption of the French soldiers was often revealed as a malevolent trauma that generated real civil wars.

The introduction of the Jourdan-Delbrel law of the 1798 actually marked a break with the past, although several armies that faced France remained set according to a traditional model. The revolutionary armies were therefore moved by a nationalist feeling whose vocation was to free the other peoples from the ignorance and iniquity of the laws imposed by the aristocracy. On paper the principles of the 1789 held up well, also because the approach of the troops to the song of the Marseillaise raised the spirit of many peoples eager to demolish, once and for all, the ancient state facilities of the Old Regime. In the new ideas there was no longer any obligation of fidelity to a king appointed by an imaginary divine will, no recruitment contract for soldiers or social differences: there was rather a state governed by fair laws and guarded by a national army that collected as reward the daily pay. Although the founding principles were really loaded with good intentions, the reality was very different because the irruption of the French soldiers was often revealed as a malevolent trauma that generated real civil wars.

The progressive disintegration of revolutionary ideals and the defeats on the field suffered by anti-French coalitions favored a new change of direction with the advent of a strong man, Napoleon Bonaparte. The First Consul, then self-proclaimed emperor in December 1805, preserved and perfected, thanks to the proposals that were of Lazare Carnot, the idea of a national army in which they would have waged - willy-nilly - all the citizens of an empire whose foundations rested on the ideas generated in the 1789. Obviously it was a deceptive and unrealistic vision because, as the Napoleonic history has shown, the good intentions of the "little Corsican" concealed a personal ambition worthy of the more eccentric Louis XIV. If in the Ancient Regime the incorporation of foreign mercenary troops was an opportunistic and purely economic fact, the advent of the Napoleonic Empire sanctioned the birth of the Grande Armée, a variegated monster in which - at least on paper - the communion of ideals and the obligation of conscription acted as a glue.

The network of family power woven by Napoleon from 1805 to 1814, had important consequences on the legislation of half of Europe and even today we enjoy (according to views) that enlightened legacy desired by a character still very much loved by Europeans. Napoleon, in his deepest essence, was an extraordinary soldier who enjoyed the presence of his grenadiers rather than the courtiers. His love for the war, however, severely cracked the relationships he had with the people, not inclined to abandon the job to be killed in who knows what lost country. Each subdued or formally allied state of France had to guarantee the emperor an adequate number of soldiers, willingly accepting the introduction of the conscription and the military laws imposed by the Napoleonic legislation.

The network of family power woven by Napoleon from 1805 to 1814, had important consequences on the legislation of half of Europe and even today we enjoy (according to views) that enlightened legacy desired by a character still very much loved by Europeans. Napoleon, in his deepest essence, was an extraordinary soldier who enjoyed the presence of his grenadiers rather than the courtiers. His love for the war, however, severely cracked the relationships he had with the people, not inclined to abandon the job to be killed in who knows what lost country. Each subdued or formally allied state of France had to guarantee the emperor an adequate number of soldiers, willingly accepting the introduction of the conscription and the military laws imposed by the Napoleonic legislation.

La Grande Armée: a European army?

The first thing we have to clarify when we talk about Grande Armée it is as this definition differs from the concept of "Napoleonic army". The historian Alain Pigeard has drawn a clear separation between the two formations, underlining how the Grande Armée was named for the first time in a letter by Napoleon to his chief of staff Berthier the 25 August 1805 on the occasion of the feared invasion of England. The mass of soldiers gathered in Boulogne in that year belonged to the first Great Army which then fought in Ulm, Austerlitz, Jena, Eylau and Friedland. From 1807 onwards the term fell into disuse because with the invasion of Spain, Napoleon divided his army into separate armies that took the name from the place where they were dislocated (Armata di Spagna, Armata d'Italia, Observation Corps of the Pyrenees Oriental, Army of Andalusia, Army of Germany, and so on).

A new Big Army was assembled in the 1811, just on the eve of the invasion of Russia, where it fought an army similar to that of the 1805, but much larger. The army corps that invaded the domains of Tsar Alexander I were the most important example of a European army, formed by different nations, small kingdoms, duchies and principalities, united not so much by an ideal, but by the will or the fear of follow a man in his foolish ambition of absolute power.

A new Big Army was assembled in the 1811, just on the eve of the invasion of Russia, where it fought an army similar to that of the 1805, but much larger. The army corps that invaded the domains of Tsar Alexander I were the most important example of a European army, formed by different nations, small kingdoms, duchies and principalities, united not so much by an ideal, but by the will or the fear of follow a man in his foolish ambition of absolute power.

Up to 1813 Europe was comparable to an immense barracks in which Italian, Swiss, Spanish, Portuguese, German (the Confederation of the Rhine), Irish, Prussian, Polish, Greek, Dalmatian, Croat, Albanian, Hanoverian and Italian regiments converged. different colonial units. The most important fact was that none of these regiments enjoyed an independent command, but formed the piece of heterogeneous armies commanded by French marshals. The only non-French general who rose to the rank of marshal was the Polish Joseph-Antoine Poniatowski, a native of Warsaw in the 1763; for the rest, Napoleon always entrusted the key to his trusted comrades in arms. To the satellite states we must then add the territories incorporated as departments directly from the Empire: from Paris to Hamburg Napoleon established 32 Military Divisions (of which 4 in Italy in Turin, Genoa, Florence and Rome) within which they were recruited soldiers who would have served in all respects as French regiments.

We can therefore define the Grande Armée a European army? Naturally, as we have seen, few of the countries adhering to the Napoleonic regime were consenting, but certainly everyone, at least at the beginning, nurtured trust and hope in Napoleon and his ideas. The tribute in military terms demanded by the empire proved however a very high price to pay, but became unbearable when added to that economic culminated with the Continental Block of 1806 that penalized several European economies.

We can therefore define the Grande Armée a European army? Naturally, as we have seen, few of the countries adhering to the Napoleonic regime were consenting, but certainly everyone, at least at the beginning, nurtured trust and hope in Napoleon and his ideas. The tribute in military terms demanded by the empire proved however a very high price to pay, but became unbearable when added to that economic culminated with the Continental Block of 1806 that penalized several European economies.

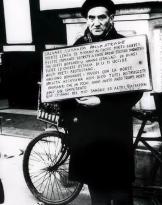

And yet - someone explains it to Trump - just that jumble of nationalities in arms were at the origin of a new European consciousness, then developed with the revolutionary movements that, in the following decades, shattered the order restored by the Restoration. Many men who led Italian independence had gained experience in the Napoleonic campaigns; many of them understood the brutality of foreign domination at their own expense, especially during the Spanish campaigns in 1808, where the enemy was the Iberian guerrilla, but also the French soldier.

The vocation of "military communion" necessarily housed also in those who opposed the Bonapartist ideals, forced to join in different coalitions. But what the English, Prussian, Austrian and Russian armies never had was the principle of unity of command since the various Arthur Wellesley, Gebhard von Blücher, Karl Philipp Schwarzenberg or Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg always acted as independent national units, led by the particular interests. The idea of a European army unconsciously desired by Napoleon was precisely this: to serve in arms for a single ideal, with a single commander. An army devoted to the protection of the Empire, but bound by common laws and economic interests.

Conclusion

It is frankly difficult to understand how the proposal of a European army can be judged offensive by an American president and above all by a leader like Trump who can not speak of "offenses" to third parties. The idea of Macron obviously falls into that height that both annoys the European partners, but from which we should perhaps learn something all, especially we Italians. Thanks to this mania of greatness, France managed to mend the tear immediately during the Second World War, but above all to miraculously transform into victories an innumerable series of defeats suffered after the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte.

It is frankly difficult to understand how the proposal of a European army can be judged offensive by an American president and above all by a leader like Trump who can not speak of "offenses" to third parties. The idea of Macron obviously falls into that height that both annoys the European partners, but from which we should perhaps learn something all, especially we Italians. Thanks to this mania of greatness, France managed to mend the tear immediately during the Second World War, but above all to miraculously transform into victories an innumerable series of defeats suffered after the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The collapses of the French army are comparable to those of Italy: the debt that France has over the allies is very high and just in the First World War did not enjoy a total victory comparable to ours. Yet the seed generated by the Revolution and then by Napoleon (who had very little French) has led France to always propose itself on the tables of diplomacy as a winning and fundamental interlocutor for any negotiation. This image - built with wisdom and intelligence - is the result of national chauvinism that has given the transalpine people that cohesion that results to be deficient in other governments, but above all in other peoples.

That the idea of a European army is born in Paris is coherent with a considerable historical trend, nevertheless its implementation could clash on the barriers of a still fragile Europe, disunited and still too enslaved to overseas interests.

(photo: Eliseo / web / US Marine Corps)