On the eve of the Great War, the Middle East was an integral part of the now decadent Ottoman Empire, considered as "the great sick man of Europe", because it was a state entity as well as a decadent victim of conflicts and infighting, without a strong army and prey to a bureaucracy unable to solve the problems that arose at the time. In the 1908 a nationalist and pan-Turkish political association, i Young Turks, took effective power, taking it from the Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who was then deposed and replaced the following year by his brother Mohammed V. The new nationalist government, which promoted a modernization and a new conception of the Sublime Porte, with the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, the reform of the army and a centralization of state power, he launched a strong repressive campaign against non-Turkish populations, such as the Arabs, who, feeling threatened by this ultra-nationalistic climate and from the more efficient infrastructure projects (such as the Hegiaz railway) on their territory, they began to oppose them through requests for independence.

The outbreak of the war meant that, with the deployment of the Ottoman Empire alongside the Central Empires, the Anglo-French, interested in the territory and its resources, supported and encouraged the Arab nationalist ferments. London was also terrified by the possibility that the Ottoman Sultan, the maximum guide of the populations of Muslim faith, could invoke jihad, the holy war, against the infidels. This scenario could have followed uprisings and attacks on British colonies by Muslims, some of which contained a strong Islamic component within.

So it was that his Majesty's government began to make contact with the Hashemite dynasty, one of the main Arab dynasties, as direct descendants of Muhammad and religious guides. The correspondence between the British High Commissioner in Cairo MacMahon and Hussein Ibn-Ali contains all the promises made by London to the Arabs: the latter would have, at the end of the hostilities, a great Panarabo State, affiliated to London (Hussein was an Anglophile, he even wished to enter the Commonwealth), but in exchange they would have to fight alongside the Entente. This was also part of the logic of the policy of the indirect rule, applied by the British even in their own colonies: it consisted of the formation of colonial elités capable of governing the colony autonomously, remaining however linked to the mother country. The imperialist country, however, would have had access to the main resources of the country, and would have been entitled to the establishment of military bases on the land of the colony.

For the Arabs, the possibility of a pan-Arab state and the liberation from the Turkish yoke were sufficient conditions to fight against the Ottoman Empire, as they desired and dreamed of an Arab territory, extended throughout the region; the Entente, however, had quite other plans for the Middle East. In 1916 a secret Anglo-French agreement was signed by the two diplomats Mark Sykes and François Georges Picot in which their respective spheres of influence were defined after the fall of the Sublime Porte: the British would go to southern Iraq, Jordan and Haifa, city port; to the French, south-eastern Anatolia, northern Iraq and Greater Syria, including Syria itself and the Lebanese territories. Although it did not play an important role in the negotiations, the Russia of the Tsars was assigned Armenia, while Palestine, the nerve center of Zionist immigration, would be placed under international control.

For the Arabs, the possibility of a pan-Arab state and the liberation from the Turkish yoke were sufficient conditions to fight against the Ottoman Empire, as they desired and dreamed of an Arab territory, extended throughout the region; the Entente, however, had quite other plans for the Middle East. In 1916 a secret Anglo-French agreement was signed by the two diplomats Mark Sykes and François Georges Picot in which their respective spheres of influence were defined after the fall of the Sublime Porte: the British would go to southern Iraq, Jordan and Haifa, city port; to the French, south-eastern Anatolia, northern Iraq and Greater Syria, including Syria itself and the Lebanese territories. Although it did not play an important role in the negotiations, the Russia of the Tsars was assigned Armenia, while Palestine, the nerve center of Zionist immigration, would be placed under international control.

This secret partition was the result of colonial frictions, never dormant, between France and England, since, although England could easily support the formation of an Anglophile pan-Arab state, inextricably linked to London, France, self-proclaimed protector of Christians in the world , would have lost power and prestige, and could not accept that a territory so rich in resources as the Middle East could end up in the British hands.

The 10 June 1916, less than a month after Sykes-Picot's signature, Hussein Ibn-Ali, unaware of the great game that was taking place behind him, fired a shot from his window, beginning the Arab Revolt. In a few days, the Arab rebels reached the conquest of Mecca, then the Red Sea and finally the city of Ta'if. Their offensive momentum stopped in the battle of Medina, in September, where the Ottoman forces, even if they underestimated the Arab problem, managed to repel and rout, with the use of machine guns, the forces of the sons of Hussein, Faysal and Abdullah . This defeat caused the British to doubt of Hashemite's actual ability to conduct a parallel war against the Sultan. In October, a British intelligence officer was sent to assess the situation: his name was Thomas Edward Lawrence, later known simply as Lawrence of Arabia, the legendary colonel who romantically defeated the Turks in the desert dunes.

Lawrence, a great connoisseur and lover of the Arab world, understood that those peoples needed adequate means and weapons to fight: that was how he convinced London to send money and supplies, necessary to constitute an effective fighting force. In the same way, English diplomacy had already set in motion, promising the sons of Hussein, Faysal and Abdullah, of the lands to be administered: Syria would have gone to Faysal, while to Abdullah Iraq. To his father, Mecca would have gone.

Lawrence, a great connoisseur and lover of the Arab world, understood that those peoples needed adequate means and weapons to fight: that was how he convinced London to send money and supplies, necessary to constitute an effective fighting force. In the same way, English diplomacy had already set in motion, promising the sons of Hussein, Faysal and Abdullah, of the lands to be administered: Syria would have gone to Faysal, while to Abdullah Iraq. To his father, Mecca would have gone.

The Hashemite forces, at the beginning of the uprising, could count on about 30.000 Bedouins, dispose of the most disparate armaments and lacking a military discipline. The arrival of Lawrence, however, changed the camps in the field: Faysal would drive 6.000 men against the Ottomans in the north, Abdullah 9.000 to the southern sector, and was also set up a regular Arab army of 2.000 men, of which 1.500 belonging to ' Anglo-Egyptian army; all this in support of the Anglo-Egyptian force of General Allenby, who had the task of defeating the Sublime Gate. To these forces were added some French troops and artillery, of the North African colonies, since the French government wanted to show more sensitive to Arab religiosity.

The Ottomans, on the other hand, had about 23.000 men, numerous artillery and German aviation located throughout the Middle East, under the command of General Fakhri. The plan worked out by them was simple: to maintain the lines of communication and the main cities, to respond with limited counter-offenses and not to bleed forces in this "tribal uprising", thus defined by the Turks, as they absolutely underestimated the problem.

Following the defeat in the 1916 in Medina, General Fakhri's army took the initiative and regained much of the lost territory. In the city of Yanbu, however, 1500 Arabs, assisted by the Navy and British Air Force, managed to repel the Turkish counteroffensive. It was however during the battle of Rabegh that the Ottomans, rejected, lost all offensive momentum and were forced, since then, to passively respond to the attacks of the Arab guerrillas.

In 1917 the situation became more complex: the soldiers of Lawrence of Arabia intensified the disturbing attacks on the Ottoman lines of communication, destroying large portions of the Hegiaz Railway, used, albeit limitedly, for the transport troops / supplies and completed in the 1914 . It was at this point that Lawrence elaborated his military masterpiece: the capture of Aqaba.

Aqaba was a port city surrounded by the desert. It was strongly defended by the Ottoman strongholds, which were teeming with defensive cannons that could only rotate 180 °. Taking it from the sea would have been a literal suicide. So it was that Lawrence decided to cross 600 miles into the desert, enlisting other militiamen along the way and to launch his offensive from the ground, taking the Ottoman garrison in defense by surprise. What makes this company more extraordinary, legendary and spectacular is not just having gone through the desert Al-Houl (terror) in that long distance, nor having won with 700 men alone losing 2, but having also attacked in July, which in those territories meant that there were temperatures above 50 ° degrees. It was an almost impossible undertaking. The conquest of Aqaba allowed Lawrence to turn it into an efficient command and logistics center, from which the offensives could continue.

Aqaba was a port city surrounded by the desert. It was strongly defended by the Ottoman strongholds, which were teeming with defensive cannons that could only rotate 180 °. Taking it from the sea would have been a literal suicide. So it was that Lawrence decided to cross 600 miles into the desert, enlisting other militiamen along the way and to launch his offensive from the ground, taking the Ottoman garrison in defense by surprise. What makes this company more extraordinary, legendary and spectacular is not just having gone through the desert Al-Houl (terror) in that long distance, nor having won with 700 men alone losing 2, but having also attacked in July, which in those territories meant that there were temperatures above 50 ° degrees. It was an almost impossible undertaking. The conquest of Aqaba allowed Lawrence to turn it into an efficient command and logistics center, from which the offensives could continue.

The war was coming to an end, but although the Middle East front could appear to the European eye as "secondary" it continued to provide numerous headaches to the Allies. Indeed, at the end of the '17, the British, in an attempt to ingratiate themselves with the sympathies of the Zionist community (and the money of the bankers) sent, in the name of the Foreign Minister of His Majesty Arthur Balfour, a letter (passed to History as "Balfour Declaration ") To Lord Rothschild, banker and leading exponent of the international Zionist community, stating how the British government was in favor of the establishment of a Jewish state. Years before, the British themselves, had tried to offer Uganda to the Zionists, with a view to forming a first nucleus of the Jewish state, without it affecting the right balance of power and tolerance present in some territories. The Jewish movement refused and then we tried to look at Palestine, although it already contained the first sparks that would have started the outbreak decades later. The Arabs, who became aware of the English declaration, and following the October Revolution, even the Sykes-Picot agreement (the Bolsheviks made public all the documents of the tsarist diplomacy) felt betrayed and used for the Anglo-American imperialist purposes. French.

The imposition of Jewish immigration in Palestine and the prospect of a future lacking a Pan-Arab Nation meant that the Arab populations themselves became disillusioned. This, contrary to what could be expected, did not deform the Arab combativeness, nor did it arrest it. In the 1918, the guerrillas continued to help Allenby's troops through attacks behind enemy lines and raids, allowing the Anglo-Egyptians to conquer Jerusalem and, shortly after, break the German-Ottoman defensive line north of the Holy City. The war got worse: the Ottomans started a strong repression and a systematic round-up campaign, destroying villages and indiscriminately killing civilians; the Arabs, enraged, took revenge by reacting brutally, disfiguring the dead and slaughtering the living.

The imposition of Jewish immigration in Palestine and the prospect of a future lacking a Pan-Arab Nation meant that the Arab populations themselves became disillusioned. This, contrary to what could be expected, did not deform the Arab combativeness, nor did it arrest it. In the 1918, the guerrillas continued to help Allenby's troops through attacks behind enemy lines and raids, allowing the Anglo-Egyptians to conquer Jerusalem and, shortly after, break the German-Ottoman defensive line north of the Holy City. The war got worse: the Ottomans started a strong repression and a systematic round-up campaign, destroying villages and indiscriminately killing civilians; the Arabs, enraged, took revenge by reacting brutally, disfiguring the dead and slaughtering the living.

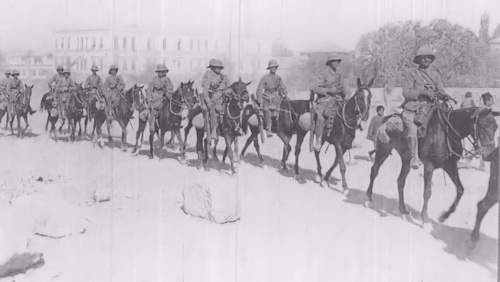

The 1 ° October 1918, following this furious war, the troops of Faysal, along with the vanguard columns of General Allenby, composed of Australian and New Zealand cavalry regiments, took Damascus, the final act of that war. Lawrence, in his book "The Seven Pillars of Wisdom", an autobiographical account of his Eastern War, describes an unbelievable triumph, an almost obsessive feast and an immense contentment for the liberation of Damascus by its inhabitants. Wilson's speech on his 14 points, particularly those referring to self-determination of peoples, excited the Arabs, disappointed by the Balfour Declaration and Sykes-Picot's revelation, who returned to covet a free and independent pan-Arab state. The revived illusion, however, would have lasted very little.

With the signing of the peace treaties in France and the establishment of the League of Nations, the territories belonging to the former Ottoman Empire were entrusted to mandator powers, including mainly France and England. Faysal, having interpreted Lawrence of Arabia, tried during the negotiations to assert his rights and those of the Arab people, without success. The decision had been made for a long time and the reasons stated, the downsizing of the claims and the negotiating capacity were not worthwhile. The Middle East would have been divided, to which the Great Syria would have been entrusted in Paris, while in Palestine and Iraq in London. On the Iraqi throne, in spite of everything, Faysal was placed, while on that Jordan Aballah; the Arabian peninsula was conquered by Ibn-Saud, another descendant of the Dynasty; Palestine, however, given its tensions between the Jewish community and that raba, was placed under direct military control of London. The administrative subdivision operated by the British once again responded to the policy of the indirect rule, that is, to the local administration, to the management of resources to the imperialists.

With the signing of the peace treaties in France and the establishment of the League of Nations, the territories belonging to the former Ottoman Empire were entrusted to mandator powers, including mainly France and England. Faysal, having interpreted Lawrence of Arabia, tried during the negotiations to assert his rights and those of the Arab people, without success. The decision had been made for a long time and the reasons stated, the downsizing of the claims and the negotiating capacity were not worthwhile. The Middle East would have been divided, to which the Great Syria would have been entrusted in Paris, while in Palestine and Iraq in London. On the Iraqi throne, in spite of everything, Faysal was placed, while on that Jordan Aballah; the Arabian peninsula was conquered by Ibn-Saud, another descendant of the Dynasty; Palestine, however, given its tensions between the Jewish community and that raba, was placed under direct military control of London. The administrative subdivision operated by the British once again responded to the policy of the indirect rule, that is, to the local administration, to the management of resources to the imperialists.

But we must not believe that the illusion infused by the British to the Arabs was only a question referring to a given realpolitik, cynical and without honor, but must be placed in a precise context: although the British wanted to control certain resources and were interested in a given territory, they had to take into account, before the aspirations of the populations involved, the needs and ambitions of the allies, like France. It had to be contained in the British plan, but at the same time it was not possible to tighten the noose around the ally's neck too much: Paris would react vehemently. For this reason, some zones of influence were granted without overdoing it (and this was done on the other side of the deployment).

In the end, those who brought us back were the Arabs themselves, those who had borne the brunt of the offensive, the yoke and the brutality of war, for the interests of the few. Probably, in hindsight, if the Arab question had been dealt with more foresight by the Allied authorities, we would not have problems in that region now, and as far as possible, it would have been pacified.

For now, we just have to learn from that nefarious experience, to make fewer mistakes.

(photo: web)