Sir Alexander Fleming, the one who discovered penicillin, was born in Lochfield, Scotland, on August 6, 1881. As a boy, he lives the country life, but he immediately shows great observation skills. He stopped to observe anything and tried to steal its secrets. He was fond of sports and shooting.

With the brothers he invented educational games in which a prize was always won. And he always won ...

In his twenties, he volunteered as a volunteer in the London Scottish Regiment, company H, to fight in the Transvaal war erupted in the 1900. The London Scottish was a regiment made up of Scots alone. The number of volunteers was very high, so Fleming did not leave for Africa.

He was a good shooter and always participated in the exercises with excellent results. In the 1914 he left the Regiment but shortly after, with the outbreak of the 1 World War II, he served in the rank of lieutenant and then captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps working in field hospitals and using his knowledge to improve first aid to the wounded on the front. before moving them to the rear.

Because of his shooting skills he was chosen to go to work in the inoculation laboratory and so he met Almroth Wright, who became his teacher. Almroth Wright himself was appointed colonel at the outbreak of the war. He left for France to create a workshop and research center in Boulogne-sur-mer. Fleming had been working in the laboratory for years and Wright took him along with his other collaborators.

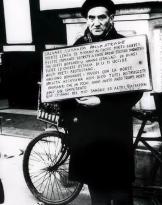

Those who knew him at that time described him as a "pale official, who did not say a word too much, but he did his job perfectly and quietly".

In the laboratory we were dealing with vaccinations, Wright in fact pushed for the whole Army to be vaccinated against Typhus. The laboratory was next to the Military Hospital and Fleming and the others daily had to deal with gunshot wounds or blast wounds and the resulting infections. Septicemia, tetanus and gangrene were the order of the day and made as many victims as the enemy's weapons.

Fleming realized that the war wounds were much more dangerous than normal because the bullets caused the death of much of the affected tissue and the necrotized tissue, not immediately removed, prevented the phagocytes, natural defenses, from reaching the microbes. It was necessary to make sure that the wounds were immediately cleaned up from the dead tissues so that the natural defenses of the human body could reach the microbes and eliminate them.

He carried out a certain number of experiments to understand what was happening in a deep wound when he used antiseptics and other medicines and realized that these almost had no effect and, indeed, in some cases were counterproductive.

Thus Wright and Fleming began their fight against the use of antiseptics and the bad practice of moving the wounded to the rear without cleaning up their wounds. Fight that led Wright to make many enemies in the high summits of military medicine.

A hospital was set up in Wimereoux in the 1918, where fractures of the femur were to be treated with deep lacerations and Fleming was appointed head of the laboratory. Fleming and his collaborators continued to improve treatment for deep wounds and also improved the transfusion techniques by saving the lives of many wounded people affected by the gangrene from gas.

Fleming faced two wars and in both he put his experience at the disposal of the world. It was certainly not the type who was pulling back in front of new challenges or slavishly followed the path traced by others.

We owe him the discovery of the properties of Lysozyme and penicillin that many lives have saved and still save. Fleming was one of the few men who in life collected the honors that were due to him.

He spent his last years lecturing (without ever abandoning the research), gathering merit but, above all, being hailed by the people who saw him as their savior, each in fact had a son, a relative or a friend saved by penicillin .

Here in a few words the military Fleming that perhaps not everyone knows.

Alessandro Rugolo