Among the rare prominent figures that have marked the history of Afghanistan in recent decades, we certainly remember the "Lion of Panshir" Massud and the Taliban Mullah Omar (photo opening). Two dissimilar figures, animated by opposing intentions with a political vision on the future of their native soil united only by the desire to wipe out the Soviets in the 1980s, but only limitedly to that period. Mullah Omar, as a simple guerrilla fighter mujahideen, stood at the head of a handful of "student warriors", plunging Afghanistan into the obscurantism of Sharia and in a war with no way out against the United States. The feeling of friendship towards Osama bin Laden and the iron defense of the values of Pashtunwali, according to which a guest was sacred and should not be repudiated, condemned the country to yet another and interminable struggle against a foreign invader. Mullah Omar had considerable experience in the field, but he did not enjoy the media echo of his Saudi friend and deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri. Indeed, many argued that Omar's contribution to the war against the infidels had been symbolic, functional only to the consolidation of the Taliban front, something that bin-Laden, by himself, would not have been able to achieve. For Washington, the bearded and one-eyed Afghan leader was simply a crude, rural, primitive and ignorant man, while tactical - strategic responsibility for operations weighed on al-Qaeda1.

After years of silence and military defeat, Mullah Omar returned to the headlines thanks to an alleged desire to treat peace with the Afghan government, so as to avert the definitive collapse of Afghanistan. In this regard, many expressed doubts because the shy Omar was always at a safe distance from political affairs. The trusty were his trusted emissaries like Mullah Mohammad Rabbani and Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, real decision-makers and administrators2.

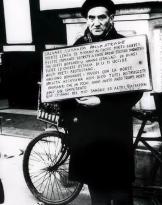

In the 2015, the government of Ashraf Ghani delivered to the medium the official news of the death of the Taliban leader due to natural causes. The rumor received no denial fueling the legend that for some Afghans Mullah Omar had never existed3. The next information was, however, even more shocking since it reported that the Emir had already died two years earlier, and that the fact had been hidden for fear of internal rifts among the Afghan guerrilla leaders. Like a monarch of Ancien Régime, the departure of the Afghan leader triggered a tough battle for his succession though, the shura Quetta unit (composed of 200 members), had already designated Akhtar Mohammad Mansour as heir (photo below). Among the first to endorse Mansour's nomination was the al-Qaeda leader, al-Zawahiri, who was aware that a division within the Afghan front would favor the growth of ISIS among the indecisive factions. The Egyptian doctor even published a video in which he consecrated the Emirate established by Omar as the first and only example of a legitimate Islamic state since the Ottoman Empire.4.

Rumors against Mansour's election came from just inside, both among some of the guerrilla leaders, and from Omar's own family, and in particular from his son, Mullah Yaqoob, although still young and inexperienced. Yaqoob's skepticism was embraced by sheer convenience by Qayyum Zakir, a former Guantanamo prisoner who, after returning to Afghanistan, became one of the most influential military leaders in the country.

The debate on the legitimacy of the successor was obviously connected to the peace programs for which no one seemed to really want to commit. Subsequently, the hypothetical negotiations initiated by Mullah Omar were widely denied, but the statements about a renunciation by the Taliban chief to the planning of any military offensive were more truthful.5. Mullah Omar remained an important charismatic leader, but nothing more: from the 2001, a convenient inaction had fatally removed him from the front line, from his most trusted men and from any decision-making debate. Another potential opponent of Mansour was Sirajuddin Haqqani, son of Jalaluddin Haqqani, influential founder of the infamous "Haqqani Network"Responsible for most attacks against the Afghan government and coalition forces. However, Mansour succeeded in ingratiating himself with his favor, appointing him responsible for the military operations of the Taliban. With the approval of Zakir, the consent of Yaqoob and the alliance of Haqqani, the newly elected Emir al-Mu'minen Mansour revoked any diplomatic approach with the Kabul government, inflaming the spirit of the Taliban who would "continue their jihad until the creation of an Islamic system. The enemy, with its peace talks and its propaganda, is trying to weaken the jihad. If we are disunited Allah is not happy and only our enemies will enjoy it. We are fighting from 25 years and we must not abandon our commitment "6.

The new Mullah, contrary to his predecessor, had immediately shown greater familiarity with the tools of politics, using his persuasive power and in some cases even blackmail: "Most observer has concluded that Mullah Mansour used cooption, appeasement and extortion in his quest to become the supreme leader after the death of Mullah Omar "7. THE'entourage of Mansour revealed an unexpected energy, made of violence, usurpations and injustices to which the Afghan army had to answer.

Military repercussions and the role of Al-Qaeda

The appointment of Sirajuddin Haqqani as commander of the armed wing had strong repercussions on the work of the Taliban. The Haqqani network, conniving with the ISI (Inter Service Intelligence) Pakistani, benefited from numerous men, financiers and a good technological mastery8. Sirajuddin's group was undoubtedly the most active in Afghanistan, not only because it was close to Islamabad intelligence, but also thanks to the support of al-Qaeda. On the contrary, since the 2001, the scanty groups of Taliban had reduced their offensive capacity, above all against the Afghan army with which they preferred to avoid direct confrontations. From the 2014 instead attacks against the so-called "soft-targets", in particular in the capital, increased. According to UNAMA estimates (United Nations Assitance Mission in Afghanistan " only in 2014 the deaths among the civilians went up to 10.548, "the highest on record in a single year with particular increase in casualities among women and children". The second operational group, alongside Mansour, were the Taliban of Mullah Mohammad Rassul, however, strangers to relations with powerful organizations such as Haqqani or the ISI of Pakistan10.

Al-Qaeda, also back from an uncertain period after the death of bin Laden, had resumed working according to a different form, elaborated by the mind of al-Zawahiri, proponent of a fragmentation of the organization in favor of many small groups operating in Worldwide. The parable of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan was descending, overwhelmed by Allied military percussion: according to an estimate by the US Department of Defense, the remaining operatives in the area reached the 100 units scattered between the historic strongholds of Kunar and Nuristan in the east, Zabul and Ghazni in the south and in the provinces of Khost, Paktia and Paktika. The opinion of the various Taliban groups on the presence of al-Qaeda was always lived in a contradictory way: on the one hand they were seen as the true cause of the defeat, while on the other a necessary evil since they guaranteed a constant flow of money in their coffers11. Today, even more than yesterday, Ayman al-Zawahiri is obliged to strengthen his position in the Afghan provinces, especially in view of his rivalry with the Islamic State. The title held first by Mullah Omar and then by his successors - Emir al-Mu'minen o Emiro dei Fedeli - it was, in fact, in contrast with that of Caliph of al-Baghdadi, judged presumptuous, illegitimate and disputed by a large part of the Islamist community. Not only: from a territorial point of view the Taliban Emirate founded by Omar remained the only one to be unanimously recognized as such and, although less grandiose than the ISIS Caliphate, it certainly benefited from an older primacy12. These figures played in favor of al-Zawahiri both politically and religiously. Also in the field of terrorist ethics, the senior al-Qaeda leader wanted to teach the young al-Baghdadi a lesson by recalling him to the sacred value of Bay c ah, or alliance, which, incidentally, the sheikh of ISIS had denied him.

Al-Qaeda, also back from an uncertain period after the death of bin Laden, had resumed working according to a different form, elaborated by the mind of al-Zawahiri, proponent of a fragmentation of the organization in favor of many small groups operating in Worldwide. The parable of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan was descending, overwhelmed by Allied military percussion: according to an estimate by the US Department of Defense, the remaining operatives in the area reached the 100 units scattered between the historic strongholds of Kunar and Nuristan in the east, Zabul and Ghazni in the south and in the provinces of Khost, Paktia and Paktika. The opinion of the various Taliban groups on the presence of al-Qaeda was always lived in a contradictory way: on the one hand they were seen as the true cause of the defeat, while on the other a necessary evil since they guaranteed a constant flow of money in their coffers11. Today, even more than yesterday, Ayman al-Zawahiri is obliged to strengthen his position in the Afghan provinces, especially in view of his rivalry with the Islamic State. The title held first by Mullah Omar and then by his successors - Emir al-Mu'minen o Emiro dei Fedeli - it was, in fact, in contrast with that of Caliph of al-Baghdadi, judged presumptuous, illegitimate and disputed by a large part of the Islamist community. Not only: from a territorial point of view the Taliban Emirate founded by Omar remained the only one to be unanimously recognized as such and, although less grandiose than the ISIS Caliphate, it certainly benefited from an older primacy12. These figures played in favor of al-Zawahiri both politically and religiously. Also in the field of terrorist ethics, the senior al-Qaeda leader wanted to teach the young al-Baghdadi a lesson by recalling him to the sacred value of Bay c ah, or alliance, which, incidentally, the sheikh of ISIS had denied him.

Despite the arguments of al-Qaeda and the danger of an internecine war, the Islamic State, already before the official declaration of the death of Mullah Omar, had begun to weave its web to take over some areas of Afghanistan. The death of Mullah Omar opened a breach, but the government of Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour enlarged it irreparably: the power vacuum, internal rivalries and disagreement over the succession gave way to a conspicuous migration of the Taliban into the ranks of the state Islamic. Su Zawahiri still weighed on the accusation of having appropriately concealed Omar's death from the Taliban: "On the one hand, it was possible that he was the death of the Taliban leader, but he could not divulge the information in deference to the Taliban's leadership . But if that was the case, to the Qaeda's effort to use the authority of a dead man to delegitimize the Baghdadi's self-style caliphate makes it complicit in the Taliban's deceit13.

The 21 in May 2016 the American intelligence officially announced the death of Mullah Mansour, eliminated by a bomb dropped by a drone (photo above). This time there was no doubt about the true date of death and for the Afghan guerrillas a new, worrying, power vacuum appeared.

Mullah Akhundzada and the rise of ISIS

In the 2016, the handover was less tortuous. The general condescension towards the election of Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada (photo on the right) was supported by religious motivations, but also because the candidate was indeed the most reliable among the contenders. Respect Mansour, the new leader reflected the humble and shy temperament of Omar: "Akhundzada [...] is to say live to simple life in the truest Deobandi tradition"14. A spiritual but non-operative involution that did not deter the Taliban from planning a new campaign of attacks in Kabul and other provinces. Precisely because they are subject to the split, the various factions acted on their own, without following a common logic and therefore laboriously controllable. From the 2015 the ISIS imposed itself as a dangerous and preponderant actor of the multifaceted Afghan scenario. The first followers of the Islamic State to contend with the primacy of the Taliban belonged to ISIS Wilayat Khorasan whose purpose was to subject the province of Nangarhar and its surroundings. The ISIS militants chose the same strategy implemented with the al-Nusra front in Syria, enlisting in their ranks the disillusioned and discontented who wanted, more than anything, the Jihad to the bitter end against the "infidels". As soon as the news of the death of Mullah Omar leaked, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi even proposed himself as a possible substitute since his immense self-esteem made him "the rightful leader of the faithful"15. The doctrinal vision advocated by the Islamic State found fertile ground in blaming the Taliban because, according to al-Baghdadi, being in collusion with the Pakistanis of the Secret Service were not consistent with the "pure" dictates of the Jihad. Moreover, according to Islamic tradition, after the death of the first Emir al-Mu'minin his followers were not bound by any oath to his successor and therefore could freely choose which side to take. In the 2014 ISIS established a fruitful relationship with the organization Therik-I Taliban Pakistan (TTP) together with many other scattered groups eager to join the Islamic State. The same year the group Beitullah Meshud Caravan - whose name consecrated the life of a terrorist accused of killing Benazir Bhutto - he swore loyalty to al-Baghdadi via Twitter. According to analysts it was evident that "ISIS likely aimed to expand its social control in Afghanistan through coercive means"16.

In light of what is happening in this last period and the media silence surrounding Afghanistan it is difficult to imagine what the future of the Taliban might be. The question everyone is asking is whether they have actually lost strength, or their guidance is transferred to "third" organizations, far from their tradition.

What possible future?

The 1 January 2015 NATO defended the country in the hands of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces. ISAF troops withdrew definitively, while a large number of soldiers (around 13.000) remained as an active part of the operation Resolute Support, useful for training and improving the quality of ANDSF. The departure of the NATO troops has again given courage to the Taliban who, however, have changed theirs modus operandi and unfortunately their goals too. As we have already pointed out, in 2015 civilian casualties have increased and in some provinces the Mullah militias have reaffirmed their presence. How things are the peace process appears a chimera and the conditions put forward by the Taliban are really unacceptable. The 23 January 2016, in Doha, Mullah's spokesman, Muhammad Naim Wardak reiterated the claims for a ceasefire: exclusion of the movement's leaders from the United Nations black list, immediate release of prisoners, withdrawal of foreign forces, extension of the law Islamic, suppression of bounty or prizes for those who had militants arrested and the composition of an interim government. The Afghan president, Ashraf Gahni, although uncertain whether to accept some points, was adamant about the possible formation of a Taliban-run government and the imposition of Sharia. The US government with the United Nations rejected the requests and in response, a few months later, they eliminated Mansour while President Barak Obama proudly asserted: "that the strike was a milestone effort in the US efforts to establish Afghanistan, while again asking Pakistan to deny terrorists a safe haven "17.

The government of Gahni does not enjoy the confidence necessary to support any negotiation, on the contrary it has several points against it - such as the lack of an economic policy and a rampant corruption - at times they make the cruel rigidity of the Taliban more acceptable. The only reality to play a fairly decisive role is the Afghan national army which, paying a high price in human terms, puts a stop to the resurrection of the guerrillas; the same NATO policy confidently follows this direction, supporting military and security apparel as it can. The Taliban are not terrorists in the strict sense of the term, although their change of strategy has forced the United States to replace the type of response: from counterinsurgency a Counterterrorism. In this, as for other things, Trump's policy is called to make very difficult choices, however the general impression is that for the Americans - as happened after the Soviet invasion - Afghanistan remains a country to forget as quickly as possible .

1 - Elias, Barbara. "The Legend of Mullah Omar." Foreign Affairs. 12 Feb. 2017. Web. 12 Feb. 2017. URL: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2015-09-01/legend-mu...

2 - Malaiz Daud, "The Future of Taliban", CIDOB Policy Research Project, Barecelona Center for International Affairs, June 2016

URL:http://www.cidob.org/en/publications/publication_series/stap_rp/policy_r...

3 - Sune Engel Rasmussen, "Taliban officially announce death of Mullah Omar", The Guardian, July 30, 2015, URL:https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/30/taliban-officially-announc...

4 - JWMG Desk, "Implications Resulting from the Death of Mullah Moar, Leader of the Taliban Afghanistan", ICT, 08 / 12 / 2016, URL: https://www.ict.org.il/Article/1870/implications-resulting-from-the-deat...

5 - Anthony H. Cordesman, “The Afghan Campaign and the Death of Mullah Omar”, Center for Strategic & International Studies, August 2, 2015. URL: https://www.csis.org/analysis/afghan-campaign-and-death-mullah-omar

6 - Ibidem, p. 2.

7 - The Future of Taliban, p. 4.

8 - Hanna Byrne, John Krzyzaniak, Qasim Khan, "The Death of Mullah Omar and the Rise of ISIS in Afghanistan", Institute for the Study of War, August 17, 2015, p. 2, URL: http://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/death-mullah-omar-and-rise-...

9 - Cordesman, p. 7.

10 - Simta Tiwari, “Understanding Taliban and the Peace Process”, Indian Council of World Affairs, Issue Brief, 28 April, 2016. URL: http://www.icwa.in/pdfs/IB/2014/UnderstandingTalibanPeaceProcessIB280420...

11 - Lauren McNally, Marvin G. Weinbaum, "To Resilient Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and Pakistan", Middle East Institute, Policy Focus Series, August 2016, p. 8, URL: http://www.mei.edu/sites/default/files/publications/PF18_Weinbaum_AQinAF...

12 - Mendelsohn, Barak. "Al Qaeda After Omar." Foreign Affairs. Np, 12 Feb. 2017. Web. 12 Feb. 2017. URL: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2015-08-09/al-qaeda-...

13 - Ibidem.

14 -. The Future of Taliban, p. 3.

15 - The Death of Mullah Omar, p. 5.

16 - Ibidem, p. 6.

17 - Kriti M. Shah, "Reconciling with the Taliban: The Good, The Bad and the Difficult", ORF Observer Research Foundation, Issue Brief, June 2016, Issue n. 151, URL: http://www.orfonline.org/research/reconciling-with-the-taliban-the-good-...